About a month before the Test series between Pakistan and Sri Lanka, Agha Zahid visited the UAE.

As head curator of the Pakistan Cricket Board , he was over to cast an eye on the surfaces the Tests will be played on in Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah. As Pakistan are the "hosts" it was a routine visit to make sure, as any home curator would, that all was well.

Home curators are home curators and so always amenable to a little whisper from the home authority. In fact, in talking about the general preparation of pitches, Andy Atkinson, the pitch consultant for the International Cricket Council (ICC), said one of the most significant factors was "what sort of pitch … the home ground authority want to be produced".

What was not routine about Zahid's visit was that nothing more than very general instructions were given, to do with the maintenance rather than the tailoring of surfaces. It was unusual enough to pique the curiosity of Mohsin Khan, Pakistan's interim coach and chief selector.

"There is no Pakistan groundsman here, even though this is a home series," he said.

And then, with a smile, added: "There must be a reason for it. This is what home advantage is, your own pitch. There must be some reason our own groundsman couldn't come."

Two days before the opening Test, Mohsin did have a word with the Abu Dhabi groundsman, Mohan Singh, however. And, rather like saying it would be nice to be a millionaire, he told him to make a "good, sporting track".

****

The discourse on pitches is an important one, not just for this series or this winter. Recently, the ICC warned Sri Lanka Cricket over the surface used in the Galle Test against Australia. The game itself was a humdinger on a dustbowl, but such surfaces are increasingly treated with a scorn reserved for misfits.

Life is being sucked out of surfaces the world over, and batsmen are the only winners.

The Tests between South Africa and Pakistan last year in the UAE were examples of a pitch being at the wrong end of the scale. The bowlers never really stood a chance. In their second innings in Dubai, when batting should pose greater challenges, the sides scored over 300 each for the loss of only three wickets.

In Abu Dhabi, South Africa opened with 584 and Pakistan 434. Six hundreds were scored through the two Tests and one mammoth double century. Even that glutton of all run gluttons, Jacques Kallis, felt compelled to criticise the flatness.

Steps have been taken to avoid a repeat. "It's about how much you over- or under-prepare," said Dilawar Mani, the chief executive of the Emirates Cricket Board (ECB).

"Last year we made a mistake as we were a bit nervous and we over-prepared. AB de Villiers [who made 278 in Abu Dhabi] probably wants to carry that wicket around with him. We know better now."

The pessimist, and the unaware, might deduce from the climate and years of run-soaked Sharjah one-day internationals that it is not possible to produce anything other than those tracks. They would be wrong, according to Atkinson, who feels the unbroken sunshine and little rain mean conditions are "the best in the world for a curator".

The soil used for the pitches at all three UAE venues comes from Nandipur in Pakistan. This soil, Atkinson said, matches well to that used in Australia and South Africa. "Having worked with these soils in the past, they proved to be excellent to produce pitches with bounce and pace, when prepared with an even cover of grass," Atkinson said.

Though the sunshine is a good thing, the overbearing heat can make matters tricky.

"It gives the curator a conundrum to solve," Atkinson said. "The pitch surface has to be dry at the start, but it can't be too dry. This pitch is supposed to last for five days, so if it is too dry on the first morning what is it going to be like on day five?"

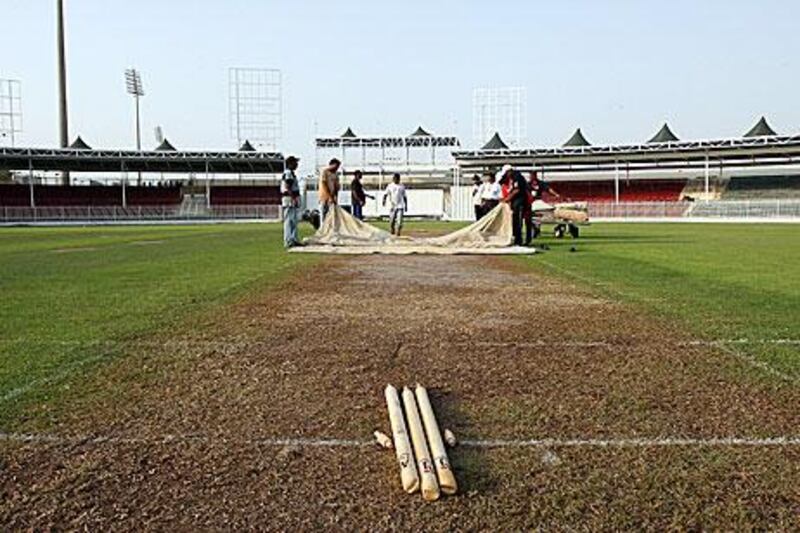

He said a curator's skill then becomes key. The initial problems with the Abu Dhabi pitch, said Atkinson (who worked on them for the 2006 ODI series between India and Pakistan) were overuse.

"When a cricket pitch is over-utilised it becomes impossible to maintain it correctly and eventually it exhibits signs such as a lack of vegetation," Atkinson said. "The gradual softening of the soil profile eventually leads to lack of bounce and pace, which normally results in surfaces too heavily balanced in favour of the bat."

Things have improved since, however, with less cricket being played and better maintenance.

In Dubai, "the pitch block has had time to settle and the grass has time to establish a strong root system," Atkinson said. "All is in place there." The variable is the instructions of the home team.

[ Sharjah is an unknown prospect because of its long absence from Test cricket. ]

[ ]

[ ]

The recent Intercontinental Cup four-day game between UAE and Afghanistan was without issues and was engrossing; it allowed for attacking batting and kept spinners interested through the second half.

****

Given the kind of surfaces produced in Pakistan for Tests recently, less instruction would be a good thing.

Alas, it was not to be.

Yesterday, some of the generous grass on the pitch was shaved off with Mohsin overlooking. Saeed Ajmal, Pakistan's off-spinner, was still minded to quip after practice that he could not see the pitch for the grass. More may go.

There is no one ideal pitch, Atkinson acknowledges. But he draws some parameters: "It is necessary that the surface is a trustworthy one, and the bounce is consistent for the first three days."

Some degree of deterioration over five days, Atkinson believes, is vital. Anything vaguely within this outline over the next few months will do.

Follow

The National Sport

on

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]

& Osman Samiuddin on

[ @OsmanSamiuddin ]