They arrived in consecutive months and left in successive weeks. Paulinho and Etienne Capoue had much in common. They were not just Tottenham Hotspur midfielders, signed in 2013 and sold in 2015. Both went at a loss. There may be some relief that they recouped £16 million (Dh90.8m) from Guangzhou Evergrande and Watford for the pair, though Paulinho cost more than that himself.

They have a symbolic value. They were part of a greater narrative, a spending spree and an experiment. They were bought with some of the proceeds of the sale of Gareth Bale. It amounted to a test of one pillar of Moneyball, and a reason why the word has almost become toxic in a footballing context. First Tottenham and then Liverpool sold their star player and, rather than looking for one replacement, invested in several newcomers and saw them struggle. After investing over £100 million, each regressed.

MORE FOOTBALL NEWS

[ Per Mertesacker: Arsenal defence ‘much stronger’ now Petr Cech has joined ]

[ Every move poses a risk but Man City may have got a bargain in Raheem Sterling ]

[ Poll: Should Raheem Sterling have stayed at Liverpool? ]

The precedent, and the antithesis, came in baseball. Michael Lewis’s celebrated book referred to the wider use of statistics to confound established wisdom in scouting. Yet it focused on the Oakland A’s as they lost three of their outstanding individuals — Jason Giambi, Johnny Damon and Jason Isringhausen — at the end of the 2001 season. Their visionary general manager Billy Beane knew he did not have the budget to recruit a first baseman, an outfielder and a closer of the same stature. Instead, with savvy recruitment, he set about ensuring the team replicated its collective output from the previous season.

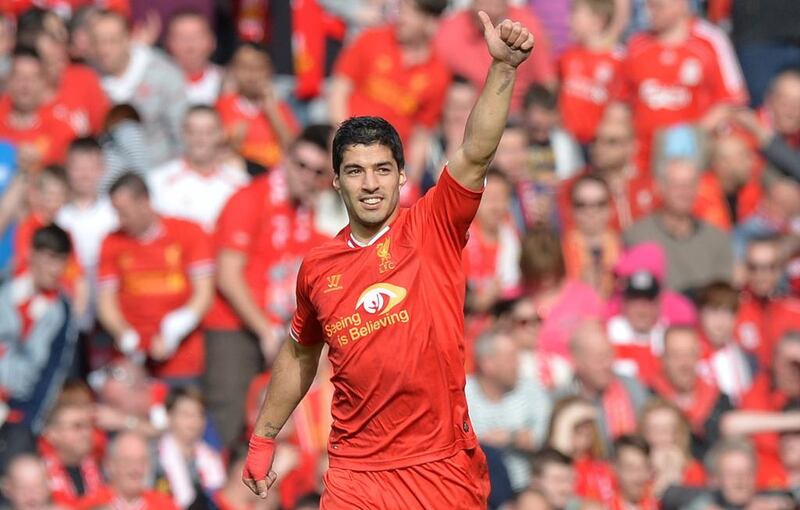

That was Moneyball. That was Tottenham’s aim after Bale’s £85 million move to Real Madrid and Liverpool’s objective following Luis Suarez’s £75 million switch to Barcelona 12 months later. If there was a winger capable of scoring 26 goals in a season, he was unattainable for Spurs. Suarez had delivered 31 goals in 33 league games; forwards of that calibre were already at the game’s superpowers and beyond Liverpool’s reach.

So each, believing themselves astute transfer-market operators, divided their money seven ways. Instead of the cult of the individual, they hoped for collective improvement. They were disappointed. Of 14 signings, only three — Christian Eriksen and Nacer Chadli for Tottenham, Emre Can at Liverpool — have proved remotely successful. Many, including Tottenham’s three club record buys of Paulinho, Roberto Soldado and Erik Lamela, and Liverpool’s buys of Dejan Lovren, Mario Balotelli and Lazar Markovic, have to be classed as failures.

Without Bale, Tottenham scored 11 fewer league goals. Shorn of Suarez, Liverpool’s mustered 49 fewer. They have resorted to spending for a second successive summer on attackers. Spurs’ goal return only recovered thanks to the emergence of the home-grown Harry Kane. Paulinho and Capoue may be setting a trend that Anfield equivalents such as Markovic and Adam Lallana will emulate in future years by making an undistinguished exit.

The legacy left by Paulinho and Capoue may not lie in the Spurs midfield, where Nabil Bentaleb and Ryan Mason came through the ranks to displace them, as much as in the examples to other clubs. Liverpool attempted to replace a match-winner with the closest possible equivalent — Alexis Sanchez spurned them to join Arsenal — but the next time a superstar is sold, the search may be for a successor, rather than an Oakland-esque group of players with a combination of attributes.

Paulinho and Capoue’s cases can be called Moneyball, but Tottenham lost much of their money. The broader question is if they represent a failure of theory or of practice. Any idea is only as good as its implementation. Tottenham and Liverpool struggled to identify correct targets and negotiate deals, as the excessive fees they paid indicated. Their additions were not all used correctly, hindered by the choice of managers who did not rate them. Whereas Oakland were baseball’s underfunded overachievers, Spurs and Liverpool became not their footballing equivalents as much as their opposites.

FOLLOW US ON TWITTER @NatSportUAE