Arsenal fans of a certain vintage have some happy memories of the 1992/93 campaign.

Their team struggled to score and were resoundingly mediocre in the Premier League but they won both domestic cup competitions.

By the standards of the time - indeed, by the standards of most points in the past - it was a successful season.

Fast forward to the present day and Liverpool may imitate them.

For Kenny Dalglish, ending a six-year wait for silverware with one trophy counts as success; given Liverpool's progress in the FA Cup, it could yet become two.

Yet a man with a glorious part in footballing history appears anachronistic in his view. Dalglish's definition is increasingly at odds with those of others - indeed, perhaps, with the owners of the club - given Liverpool's main goal for the season was to finish in the top four.

Two weeks ago, the Scot argued that there were many measures of improvement. He was mocked for including a lucrative kit deal, which he did not negotiate, in his argument, and if he is right to rationalise that results are not the only gauge, the FA and Carling cups are the sideshow.

The table, in the words of the cliche, never lies and the league is the ultimate barometer of progress - or in Liverpool's case, a lack of it.

They have fewer points than at this stage of the last two seasons, traumatic campaigns of underfunding and infighting.

In a week of back-to-back defeats to teams in the relegation zone, their league campaign has gone from underwhelming to utterly unacceptable.

On points, they are far nearer the foot of the table than the top. They have scored half as many goals as the Manchester teams. They have only won five of 15 league games at Anfield, the fewest since this point of the 1953/54 season, which culminated in relegation.

Compile a league table for 2012 and Liverpool are in the bottom three, with eight points from 11 games. They have lost five of the last six, winning only against a weakened Everton side.

If that is a blur of statistics to some, to others it is incontrovertible evidence.

Dalglish's talk of tiredness and his mantra that his side have suffered from misfortune convince some.

Yet it is worth remembering that Liverpool's principal owner, John W Henry, is a man who made his money as a trading adviser by separating emotion and instinct from decisions and analysing the numbers.

It is an approach that he took successfully into baseball. Henry is an advocate of sabermetrics, the principle behind the book Moneyball - indeed, he is a minor character in the film - and yet Liverpool are the most inefficient team in the Premier League.

In Saturday's 2-1 defeat to Wigan Athletic, they lost to the other side with the lowest chance conversion rate. They stand three points ahead of Swansea City, whose entire squad cost around half the £20 million (Dh116m) Liverpool paid for Stewart Downing, a winger without a league goal for the club. Some £115m went on buying players in 2010, and even if £78m of it was recouped, much of it was misspent.

Unlike Tom Hicks and George Gillett, Henry and Tom Werner, the chairman, have backed their manager in the transfer market.

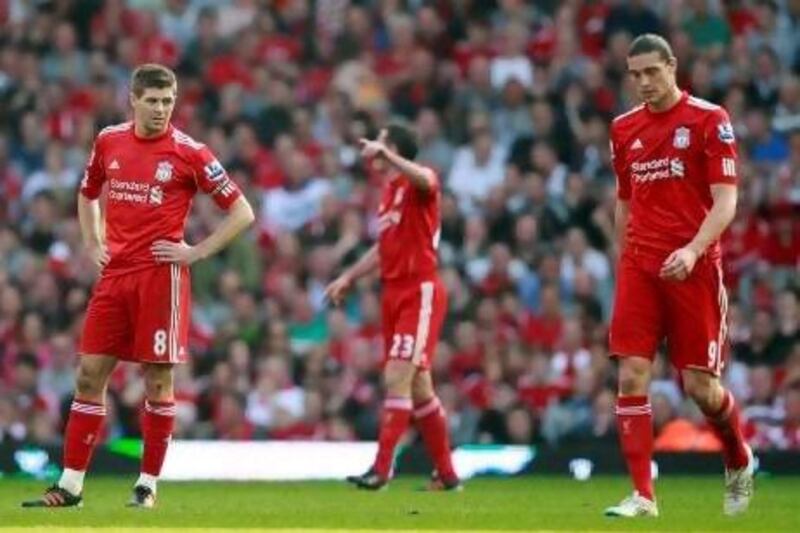

There are legitimate questions for Dalglish to answer: why Andy Carroll, the club's record signing, does not command his confidence enough to start more often; why Downing delivers so little and plays so often; what Jordan Henderson actually does. None seem to have the personality required to play for Liverpool. Much as Dalglish emphasises the team in his comments, his side remain reliant on individuals, whether Luis Suarez, Craig Bellamy or Steven Gerrard, for attacking inspiration.

On Saturday, the manager, whose recent comments have hardly increased his credibility, suggested Liverpool may need to change their philosophy "by not playing the lovely football we have been". Beauty is famously in the eye of the beholder, but each of the top four sides are far more watchable and more prolific.

Yet Dalglish has long been able to carry his devotees with him in any argument.

His legendary status at Anfield accords him advantages others do not enjoy and offers insulation when his side underperform. He benefits, in short, from being Kenny Dalglish.

That has put Henry and Werner in a bind. They could not appoint anyone else and cannot dismiss Dalglish until and unless the diehards desert their idol and give their tacit approval to his removal. It is why Dalglish's fate will be determined by feelings, not figures.

The owners are too astute to risk a mutiny on the Kop. Yet it is a safe assumption that, while Liverpool may emulate Arsenal's class of 1993, Henry finds more to admire in the modern-day Gunners. Sixteen points ahead of Liverpool, on course for a 15th successive season in the Champions League and having reached its knockout stages, they are in the black in the transfer market and have had the more profitable year.

Dalglish's is a sepia-tinted interpretation of success. By 21st-century criteria, it is underachievement.

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]