Maya Angelou, the American poet, once wrote: "I long, as does every human being, to be at home wherever I find myself." It is an emotion that most of us can relate to, unless we are cricketers or footballers playing a World Cup.

Home advantage counts for a lot in sport. Some stadiums have been compared to fortresses or citadels, and have an aura that can intimidate visiting teams even before they set foot on the park.

No visiting team won a Test match at the Kensington Oval in Barbados between 1935 and 1994. Carisbrook in Dunedin, New Zealand, was an All Black stronghold until it was closed this year. Rugby teams that played there quickly understood why it was called the House of Pain.

When Elvir Boli scored for Turkey's Fenerbahce at Old Trafford in October 1996, it ended Manchester United's unbeaten home record in European competition that had lasted four decades. And in the days when Liverpool reigned supreme, Bill Shankly said of the This is Anfield sign in the tunnel: "It's there to remind our lads who they're playing for and to remind the opposition who they're playing against."

Home comfort, though, is rare in the context of a World Cup. There was a time when hosting a football one gave you a pretty good chance of winning it. England did so in 1966, and both West Germany and Argentina were hosts when they won in 1974 and 1978. Since then, however, only one host nation has come out on top - France in 1998.

It is very different when the ball is oval. The rugby World Cup of 2007 marked the first time that a host nation had not at least made the final. New Zealand in 1987 and South Africa in 1995 won on home turf, while England (1991) and Australia (2003) failed only at the final hurdle.

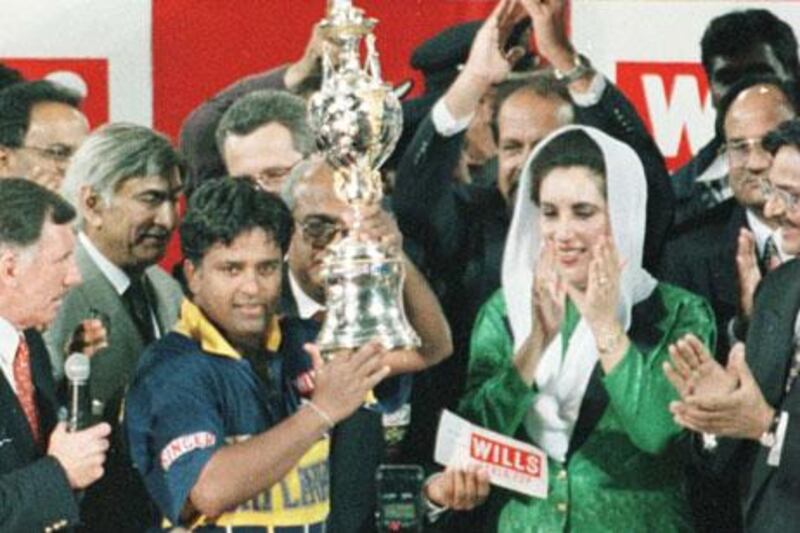

In cricket, the pressure of playing at home appears to afflict even the best teams. The mediocre ones do not have a chance. Only one team - Sri Lanka, co-hosts in 1996 - have managed to live up to home-crowd expectations and they were helped by exceptional circumstances.

Australia and West Indies declined to play after security concerns and forfeits granted by two teams that would make the semi-finals helped ease Sri Lanka's path.

By and large though, hosting the event has been the kiss of death. England reached the semi-finals in the first three Prudential World Cups, but the 1979 final was a one-sided affair remembered for Viv Richards' masterful 138, a breathtaking 66-ball 86 from Collis King and Joel Garner's yorkers that ended the home challenge.

India and Pakistan were both heavily favoured in 1987, the first time the subcontinent hosted the event. India were defending champions, and had also won the World Championship of Cricket two years earlier. But after breezing through the group stage, they came a cropper against Graham Gooch's repertoire of sweeps in the Mumbai semi-final.

Across the border, Pakistan made similarly emphatic progress into the final four. But with the Gaddafi Stadium in Lahore abuzz with excitement, they stumbled against the pace and accuracy of Craig McDermott. Allan Border's unfancied Australian side won by 18 runs, exactly what a nerveless young man called Stephen Waugh had scored in Saleem Jaffar's final over.

Four years on, when Australia defended their title, they were coming off the longest of summers. A tired team seldom got going, with a dramatic one-run victory over India at the Gabba one of the few highlights of a disappointing campaign.

Across the Tasman Sea, New Zealand did much better, topping the league table and then dominating three-quarters of the semi-final against Pakistan. But then a 21-year-old Inzamam-ul-Haq came to the crease and with Javed Miandad there to guide him, New Zealand's dream was extinguished.

English cricket reached its nadir in 1999 and that was reflected by a World Cup misadventure that ended long before the Super-Six stage. Eight years later, West Indies did make the Super Eight, but were so poor that a fan held a gun to a player's head in Grenada when he felt he had been out too late partying.

But no host has ever underachieved quite like South Africa in 2003. Ambushed by Brian Lara's brilliance on the opening day, they were then beaten by a combination of Stephen Fleming's New Zealand and Duckworth-Lewis before the unkindest cut of all in Durban. With the dressing-room unable to make sense of the chart with par scores, Mark Boucher patted back the last ball before the rain came down against Sri Lanka. It was a joke rather than a choke, only 42 million people were not laughing.

For India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, the challenge over the next six weeks is to cope with the familiar.