It is tempting to conclude that by beginning a decade lumbering through a match-fixing inquiry and ending it being shredded in a criminal spot-fixing trial, Pakistan cricket has acquired an inherent corruptibility. Many have already arrived at that conclusion. It is actually difficult not to.

A freshness to Pakistan and Sri Lanka sides ahead of Test

While the two cricket nations play each other regularly, each team has a new look since their last Test meeting in 2009.

Indian cricket:

Pass the remote control.

[ Read article ]

Australia comment:

Howard's way is not without risks for Cricket Australia.

[ Read article ]

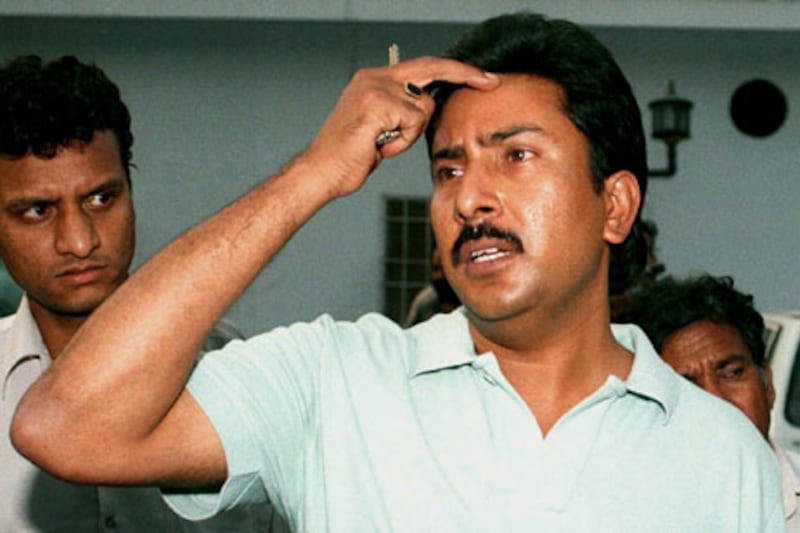

The Justice Qayyum commission, which began its work in 1998 after four years of increasing noise about match-fixing (and a couple of earlier inquiries), was comprehensive in the scope of characters it heard from and the sheer weight of hearsay and rumour it tried to document and make sense of.

But it was left incomplete by a lack of real, tangible evidence. Audio tapes of alleged set-up meetings between players, secretly recorded by Rashid Latif, were available and heard, but were of such poor quality and questionable editing, they had to be largely discounted.

There was also the first

News of the World

(

NOTW

) sting, Mazhar Mahmood catching Saleem Malik on video, but that came in the summer of 2000, by when the inquiry had been completed and was awaiting publication. Even in that, Malik was caught claiming much, but doing very little.

The commission was very much aware of this, sifting through all the smoke without ever locating the fire. It refers to it throughout the report, pondering at the very start the burden of proof in such a commission, which was neither a criminal nor a civil trial.

The final document is an eminently readable one, in the way state documents are, passing off statements of great import in such dry and clumsy legalese so that you don't even realise immediately the impact of what has been said.

Whatever credibility the report and its recommendations had, however, were reduced six years later, by the author himself, when he acknowledged he had been soft with the punishments of some big names. That confession captured something of the entire nature of the exercise and it set the tone for the decade.

From Southwark Crown Court in London - and

[ the Doha hearings ]

earlier in the year - there has been less smoke and fog. A very different picture has emerged, far clearer than any that did from the Qayyum inquiry.

The second

NOTW

sting and subsequent police investigations have gathered far more of what might be considered tangible evidence.

So it has been a bruising couple of weeks, particularly because of the pace at which proceedings have moved. At the time of the Qayyum commission, details crept out slowly over two years, softening the impact a little. In London, every day has brought a revelation.

But in a way both, inadvertently, document a certain helplessness in preventing corruption. How do you stop something you can't prove definitively is even happening, unless, as was the case with Hansie Cronje, the player confesses? Or, as has happened in the ongoing criminal trial in London, the evidence is of the nature it is, and generated by a tabloid newspaper?

Indeed how do you prevent it in any sport? A no-ball in cricket, a poor back pass in football, a shanked forehand in tennis (to pick from just three sports where corruption has been an issue); how can you ever know?

The very nature of competitive sport, of humans actually, is such that there will be variance in performance, in will, in thought, in motivation, in greed. How can you identify what is deliberate and what isn't?

It is this feeling, this paranoia, that has been felt most sharply over the last decade in Pakistan. It has coursed through all their losses, collapses, run-outs, dropped catches, and strange, unexplained meetings between players and others on tour.

It has fuelled the post-cricket career of Sarfraz Nawaz without him having to ever be a commentator. He has been attending the London trial, sitting in the public gallery incidentally. This fodder will sustain him until the end of time now.

It has meant that the answer to the question of whether Pakistan cricket is corrupt is actually not even important.

Of course it isn't, just as entire nations and people within a system are not corrupt. But that the question is pertinent and feels the need to be asked in the first place, through 10 years, that is defeat enough.

It has not been a corrupt decade, but beyond doubt it has been a careless and abysmal one.

A host of former players never cleared or convicted by Qayyum have hovered around in various capacities.

Men such as Yawar Saeed and Intikhab Alam continue to find themselves around the administrative set-up. Both were present in management through the mid and late 90s, when the first murmurs of fixing emerged and unforgivably both were still around during the latest. At best, they have been guilty of gross negligence twice.

The result has been a stench that has never quite gone away and it doesn't look like going away for a while still.

Whatever happens to the players on trial in London will happen. But more names have been thrown about, names which became public in Pakistan some time ago. This newer batch of players now also stand not fully exonerated, not fully guilty, neither by the

[ Pakistan board ]

's integrity committee nor public opinion.

So even if the trial may well end soon, the tribulations may not for some time.

Follow

The National Sport

on

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]

& Osman Samiuddin on

[ @OsmanSamiuddin ]