The suicide bombings in Russia serve as a chilling reminder of what the Winter Olympics represent to terrorists: a high-profile target with more than 2,500 athletes, some of them world-famous, waving the flags of nearly 90 nations.

So, while many Olympic leaders offered reassurance in the days after two bombings 400 miles from Sochi killed at least 31 people, some of those set to compete in the Games spoke of a different reality. They know their security is never a sure thing.

“I am concerned,” said Jilleanne Rookard, an American speedskater. “I’m scared their security may be involved. I don’t know if I necessarily trust their security forces. But they don’t want a national embarrassment, either.

“I use that thought to relieve some of my worry. I’m sure they want to save their image and their pride.”

Authorities in Russia vow the athletes will be safe, even though they will be competing in a city 300 miles away from the roots of an Islamic insurgency that has triggered security concerns for the Games, which start February 7.

The country has spent a record US$51 billion (Dh187.4m) preparing for its first Winter Games and has promised to make the Games “the safest in Olympic history”.

Alexander Zhukov, president of the Russia Olympic Committee, said the bombings did not spark a need for additional security measures because “everything necessary already has been done”.

Johan Franzen, the Swedish hockey player from the Detriot Red Wings, sees things a little differently. “I’m sure after this, the security will be higher than they intended from the start,” he said.

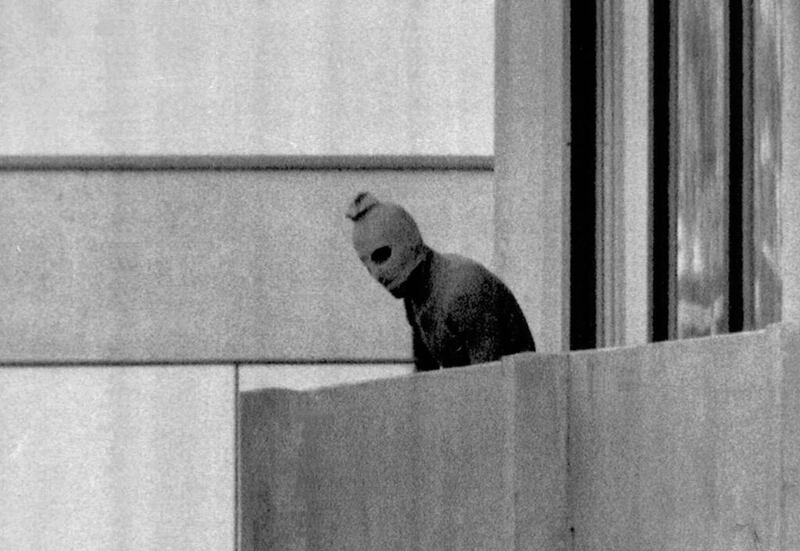

The threat of terrorism at the Olympics has been in the forefront since 1972, when members of a Palestinian terror group invaded the Olympic Village in Munich and killed 11 members of the Israeli delegation.

Security rose to a new level at the 2002 Salt Lake City Games, which came five months after the September 11 attacks.

Improvements in technology, along with ever-present threats of terrorism, have turned security into a top priority for any country hoping to host the Olympics.

Among the security measures Russia has put in place for this year’s games is a requirement that all ticket holders obtain and wear “spectator passes” while attending events.

To get a spectator pass, fans have to provide passport and contact information to authorities.

Thomas Bach, the International Olympics Committee president, this week wrote a condolence letter to Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, in which he expressed “our confidence in the Russian authorities to deliver safe and secure games in Sochi”.

On Tuesday, in his New Year’s message, he said that terrorism “must never triumph” and that he believes Russia will deliver “safe and secure” Winter Olympics.

Meanwhile, a number of Olympic leaders and federations signalled their confidence in the host country. “When we come to Sochi, it will be impossible for the terrorists to do anything,” the Norwegian IOC member Gerhard Heiberg said.

“The village will be sealed off from the outside world. Security has been our priority No 1 ever since Sochi got the games.”

The US figure skater Ross Miner, who won silver in Vancouver, is well aware of the vulnerability of major sporting events.

The theme of the New England native’s long programme is “Boston Strong”, about the city’s resilience after the marathon bombings last spring.

Miner recalled the 2011 world championships in Moscow as “by far the most intense security I’ve ever had at a competition”, with skaters going through metal detectors to enter the venue.

US speedskaters, however, have different memories of Moscow. They arrived for a 2011 World Cup event the same day a suicide bomber killed 35 people in an attack on the city’s Domodedovo Airport.

“It’s terrible we have to live in fear, but that’s just kind of how it is,” the two-time gold and silver medallist Shani Davis said.

Since the widespread use of metal detectors was introduced to the Olympics in 2002, every subsequent Olympics has brought its own set of challenges and responses.

At the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Chinese authorities introduced identity checks for opening and closing ceremonies. In London last year, there were no identity checks, but combat jets patrolled the city, and surface-to-air missiles were set up on rooftops.

Russia’s security effort is greater than Beijing’s or London’s, said Matthew Clements, an analyst at Jane’s, in a recent interview with the Associated Press.

The three-time Olympic ski-jumping champion Thomas Morgenstern of Austria said he remembers seeing sharpshooters roaming the woods in Sochi during a World Cup event last year.

“Of course you’re having thoughts about it. But when we are at the Olympic Games, that will be one of the safest places, for sure,” Morgenstern said. “I think they are in control.”