When he was a boy growing up in the Philippines, the new general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers had a problem with his cricket swing.

It had been corrupted from playing baseball, his favourite sport, despite his Pakistani-Canadian heritage.

“I held the bat with a baseball grip; my cousins weren’t impressed,” Farhan Zaidi conceded with a laugh in a phone interview, while noting that he dabbled in cricket when visiting relatives in Pakistan as a child.

“A foul ball was a good result. I couldn’t get used to that.”

[ More in MLB: Pair of Washington Nationals minor leaguers train talent in Dubai ]

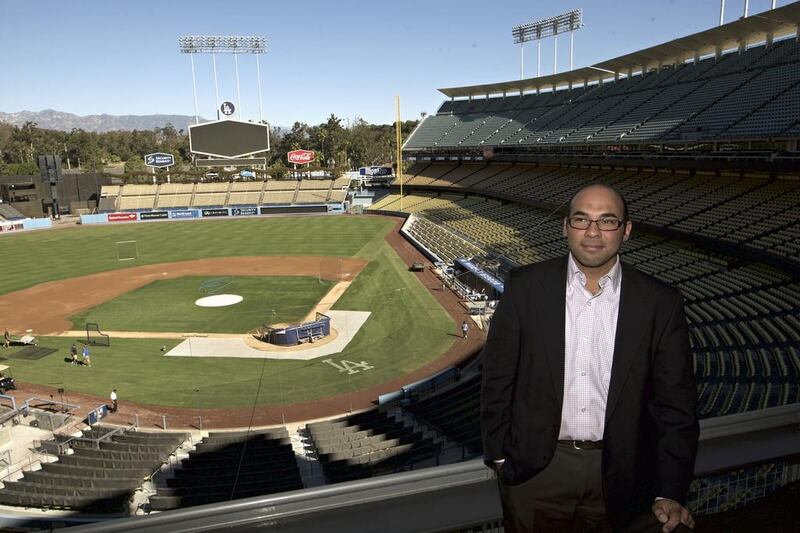

Born in Canada to Pakistani parents, raised in Manila, and educated in economics at such prestigious schools as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California-Berkeley, Zaidi’s eclectic cultural and academic backgrounds are also unique to baseball. He is the first Muslim general manager of any major professional team in North America.

“I’m a big proponent of diversity in our game,” Zaidi, 38, told reporters at his first Dodgers press conference, alluding to his religion. “So from that standpoint, I’m proud of it.”

His connections to his parents’ birthplace remain solid. Earlier this year, he and wife Lucy visited his grandmother in Pakistan. They stopped in Dubai on the way back to spend time with an uncle who is a pilot with Emirates. An aunt is a political journalist in Pakistan who regularly sends her opinion pieces to him.

“I try to stay up to date,” said Zaidi, who brightened at the mention of Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani school girl who survived an assassination attempt and a Taliban bullet in her head for supporting women’s educational rights.

“She is an inspiration, for sure, for everything she went through,” he said. He said her journey to the US “to raise awareness on an international level about the challenges Pakistani people face every day – it’s a terrific story.”

And a singular one. There are relatively few people of Pakistani heritage in North America’s public eye, which also makes Zaidi something of an anomaly.

But his entry into the upper levels of Major League Baseball (MLB) management also says something about the changing landscape of the game itself.

Hunches are out. Intellect is in. Playing baseball is one way to understand the sport. Studying baseball is another. A player’s history may not be as important as what statistical analysis and probability predict that player’s future will be.

Today every team has an analytics department, staffed with computer-savvy, numbers-oriented people, who use complex data gleaned from the results of every pitch in every major-league game.

Welcome to Zaidi’s world.

Billy Beane, the Oakland Athletics general manager who gave Zaidi his first baseball job, calls him “absolutely brilliant”.

Beane told the San Francisco Chronicle last spring: “The ability to look at things both micro and macro is unique, and Farhan could do whatever he wants to do, not just in this game, but in any business or sport.

“I’m more worried about losing him to Apple or Google than I am to another team.”

As it turned out, he did lose Zaidi to another team, and one of baseball’s most successful, in the Dodgers. Either way, it was an improbable path for the son of Pakistani parents.

Zaidi’s father, Sadiq, was a Britain-educated engineer who got a job in 1968 with a mining company, in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada – where Farhan was born.

By the time Farhan was three, his father had moved the family (Farhan has an older brother, a younger brother and a younger sister) again, to the Philippines where he worked for the Asian Development Bank.

His father loved cricket, taught the children to play and took them on visits to Pakistan in summer. But the family also took vacations to Canada, where Farhan had gravitated to baseball. He supported the Toronto Blue Jays, collected baseball cards and played first base in youth leagues and for his international school in the Philippines through his teen years.

He also was an avid fan of early analytics pioneer Bill James, who published an annual book, Baseball Abstract.

During the 1980s, Zaidi told the Toronto Star, “I was able to buy that book and absolutely devour it cover to cover before that bookstore either went out of business or stopped carrying that book because I was the only person buying it.”

But he did not envision himself working at the MLB level until he read Moneyball, the Michael Lewis book about Beane and the Athletics, and their often successful advanced-metrics approach to evaluating players.

“It always seemed to me that to work in a baseball front office, you had to have played the game at a high level, or been a scout or a coach,” he said. “It didn’t seem like a career you could access from a business background.

“When I read Moneyball, I thought, ‘I do have this skill set.’”

Zaidi had graduated from MIT with a degree in economics, and first channelled his love of baseball into a job as development associate for Small World Media, the fantasy sports division of The Sporting News. He also had worked as a management consultant for the Boston Consulting Group.

He was doing graduate work at Berkeley in behavioural economics in 2005 when he applied for a job the Athletics had posted in Baseball Prospectus.

He impressed them by bringing a binder filled with projections for every player on the team. He also ingratiated himself with Beane over shared passions for the British rock band Oasis and football. Zaidi is a devotee of the Italian national team.

The next step was telling his parents he got the job.

He told ESPN.com: “I was like, ‘How am I going to tell them I’m taking this, like, entry-level, US$30,000-a-year (Dh110,000) job in baseball?’ But they were so thrilled and happy for me. I probably didn’t give them enough credit for knowing it was a dream of mine.”

Zaidi eventually advanced to assistant GM, in Oakland. He has been credited, most recently, with pushing for the signing of Yoenis Cespedes, who was something of a mystery coming out of Cuba, and switching outfielder Brandon Moss to first base, where he thrived.

When the Dodgers revamped their front office in October, their new president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman – another new-wave analytics proponent – brought Zaidi on board.

It prompted a Los Angeles baseball writer to question the Dodgers’ new penchant for filling their front office with stat “geeks”.

Zaidi, known for his sense of humour, sought out the sceptical reporter at the first press event and told him he had brought his screwdriver, in case the writer needed help fixing his laptop.

Asked about leaving Oakland, and his sterling reputation as the Athletics’ top analyst, Zaidi joked: “They actually cut out part of my brain on that and kept it there.”

But Zaidi also assured old-school Dodgers fans he is not one-dimensional in his approach, and had great respect for on-field scouts.

“I view any new stat or metric with an inherent scepticism,” he said. “There’s always something that is missing.”

What is clear in his one-of-a-kind story is, he hasn’t missed much – after those early whiffs with a cricket bat, anyway.

sports@thenational.ae

Follow us on Twitter @SprtNationalUAE