PONCE, Puerto Rico // Emilio Navarro swiveled his hips several times, then bent over to touch his toes. Not bad for someone who is 104 years old. He gets around without a cane and is known to go dancing, now and then. He does not use glasses, either. "And I don't have many wrinkles," he said in Spanish. He smiled, then conceded in English: "Just a little bit."

The former professional baseball player is not being honoured for being spry. He is being honoured as America's Outstanding Oldest Male Worker for 2010. Navarro still keeps the books and controls the finances at the game-machine business he started. Navarro, believed to be the last surviving player of the Negro American League, was chosen for the honour over dozens of candidates nominated in 30 US states by Experience Works, the country's largest non-profit training centre for older workers.

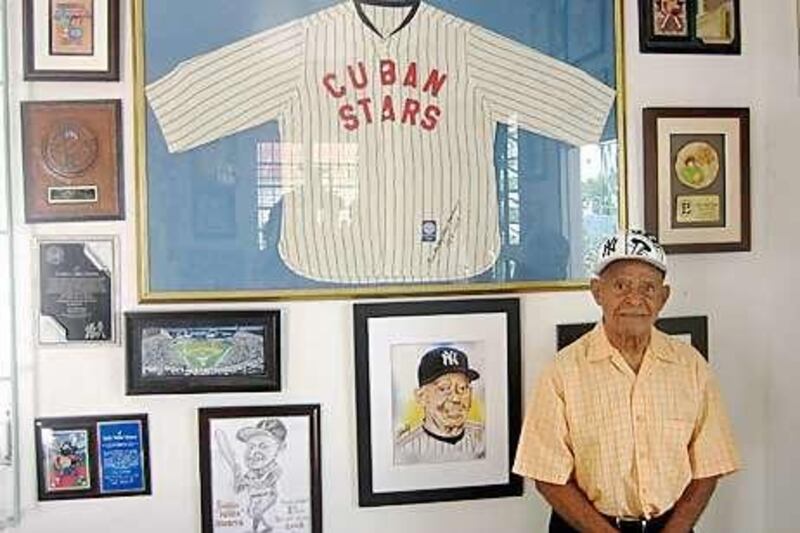

Navarro , whose nickname is Millito, began working at age 12. He cleaned shoes, sold newspapers and hawked "dulce de coco", a popular coconut treat in Puerto Rico, to help his mother financially. "She didn't know how to read or write," he said. He did not enjoy those jobs, but eventually his passion, baseball, gave him a living. At the age of 17, Navarro signed with the Ponce Lions in Puerto Rico and despite standing only 1.65m went on to play for the New York Cuban Stars in one of the black leagues in the US.

He later played in the Dominican Republic and in Venezuela. Navarro then worked as a coach and athletics teacher at schools in Ponce and Caguas. He also managed a baseball stadium in Ponce for 10 years, the job that proved his least favourite. "To be in that place and not be able to play ?" he said, his voice trailing off. "I didn't like it." Navarro later opened the game-machine business, Shuffle Alley, which his sons now run. But Navarro still works, keeping the books and making financial decisions.

"My sons work for me now," he said with a laugh, pretending to rake in cash with his hands. "I count it and I divide it into equal parts. And there's a little bit for Millito, too." Navarro has no secrets for staying young. He follows just two rules: help those who need it and show respect to everyone. "That is very important," he said. One of his sons, Eric, 61, cleared his throat. "Love God above all things," he reminded his father with a smile.

"Ah, yes," the elder Navarro responded. Navarro lives alone in the house that he built for his family in the late 1950s. His wife died more than two decades ago at the age of 62 from breast cancer, and Navarro's sons sometimes mention the benefits of a nursing home. "He makes a face and we leave," Eric said. "He defends his privacy." Lillian Ruiz cooks for Navarro every day and cleans the house, arriving at 8am and leaving by 2pm.

"He likes to be alone," she said. "He is very clean. He tidies his room every day." Navarro likes to sit on the balcony and sometimes asks Ruiz to bring a couple of dollar bills, which he floats down to a pleading homeless person below. He also likes to dance and favours blondes if he goes out in search of some danzon, a Cuban dance that incorporates mambo. Navarro, whose 105th birthday is next month, got a pacemaker 15 years ago and has had new ones put in at least twice, his son said. He has high blood pressure yet he walks easily.

"Dad is an exception," his son said. "He has stretched the bubble gum." * AP