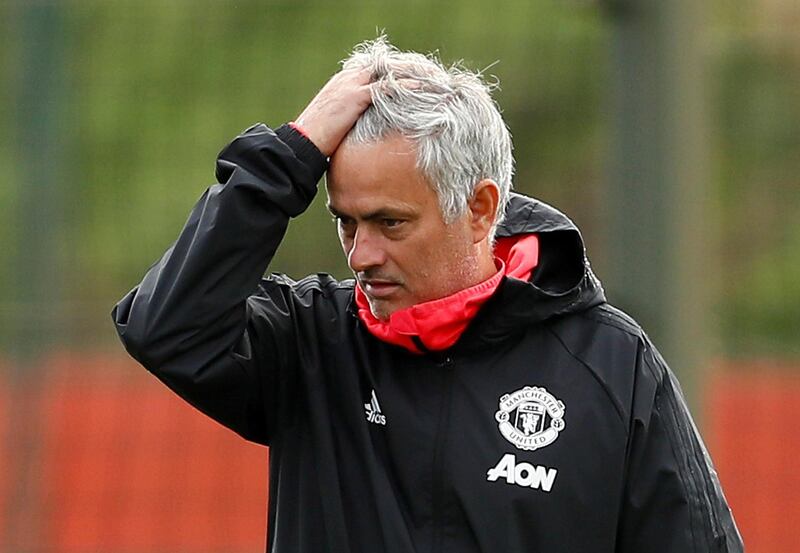

If it is a time of year for reflection, Jose Mourinho has more time than most and a greater need for reflection.

He ends 2018 as he finished 2015, unemployed, dismissed amid acrimony and underachievement. Once may have been an anomaly. Twice bears the look of a trend.

When history repeats itself in unwanted fashion, it ought to prompt self-examination. Mourinho’s career is at a crossroads.

There are suggestions Real Madrid and Inter Milan would offer him a second spell at clubs he left in contrasting fashion. If not, the map of Europe’s elite destinations could be filled with signs barring Mourinho from entry.

And what then?

There could be lucrative offers from further afield, but enough to stimulate a man accustomed to competing for the major prizes and who seemed disenchanted at Manchester United? One whose teams often act like underdogs could take a lesser job, but it would not come with the kind of budget he tends to demand.

By choice – others’ and his – Mourinho could be marooned in an unhappy exile.

Manchester United never scored more than four goals in a game during Jose Mourinho's 144 matches in charge.

— Daniel Storey (@danielstorey85) December 22, 2018

They have done it in their first game after his sacking.

Not football seems to bring him happiness any more. Without the financial need to work, management has looked an addiction, not a pleasure, of late. It seems to have made Mourinho miserable and he, in turn, has made others gloomy.

As a short-term solution, replacing him with Ole Gunnar Solskjaer, who seems in love with the idea of United, offers an ideal antidote. An enthusiast was just what United needed last week.

A common denominator among many managers, whether those making an early impact like Ralph Hasenhuttl, those at the top of their trade like Jurgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola, or men 15 years Mourinho’s senior such as Neil Warnock and Roy Hodgson, is a sense of enjoyment. Mourinho appears to have lost that.

He is at his best when there is a twinkle in his eye, when his mischievous streak is apparent, when he exudes a sense of control. Not of late.

His most formidable sides have excelled at exerting control. Much has rightly been made of the feeling that, tactically, Mourinho seems trapped in the 2000s, playing a different brand of football to Klopp, Guardiola, Mauricio Pochettino, Maurizio Sarri and Unai Emery.

Analysis ought to prompt Mourinho to wonder if he can adapt to the times in a way Alex Ferguson managed to when he was both constant and chameleon.

______________

More on Mourinho's departure:

In pictures: From Matt Busby to Jose Mourinho - list of the Manchester United managers

[ Tottenham's Pochettino to Manchester United? Arsenal's Emery sees no reason for it ]

'We are alone': Guardiola offers his sympathy to Mourinho after manager's dismissal

Mourinho was not a popular figure at Man United, but lack of results led to sack

Caption this! Pogba's hilarious reaction to Mourinho's departure from Man United

Mourinho profile: Once the face of gleaming modernity, now more a toxic dinosaur

______________

It is not merely a question of strategy. With the odd exception of seeming throwbacks like Nemanja Matic, Marouane Fellaini and Scott McTominay, Mourinho does not seem to like the modern footballer. It has been a recurring issue across his time at Real Madrid, Chelsea and United.

The previous generation of footballer loved Mourinho. Without that loyalty, his siege mentalities function less well when his teams come under attack.

Instead of devotees and trophies, Mourinho has been left with negativity and narcissism. The reminders of his glory years feel pertinent; it is just that it is Mourinho himself who keeps bringing them into the conversation.

Wayne Rooney taking out all of Jose Mourinho's files. I'm here for this 🍿

— Davo 🇱🇸 (@David_Mapheleba) December 23, 2018

pic.twitter.com/2e22rXCZIh

From 2002 to 2012, he had a decade that is almost unrivalled in football history, winning seven league titles in four countries, culminating in dethroning one of the finest sides ever, never finishing lower than second, winning two Uefa Champions League trophies and doing so with clubs who had no recent history of getting remotely close to claiming the grand prize.

Yet it is now five seasons since Mourinho’s last Champions League semi-final, nine since he won it. He no longer represents the promise of continental triumphs or the guarantee of domestic success.

It leaves one of the game’s all-time greats with an uncertain future. Where does Jose Mourinho go from here?