You know we are living in strange times when a mob of Millwall fans are the good guys. But that is what happened in London one night this week.

As gangs of masked looters swarmed over the capital, outnumbering the helpless police, scores of the club's supporters banded together to protect the shops and businesses in their local "manor" of Eltham.

In a rare moment of comedy during a grim week, the traditional Millwall chant of "No one likes us!" was replaced by "No one loots us!"

It was a minor incident, but one which might allow the English football family a secret glow of inner smugness. When it comes to public disorder, it is a family that rarely has much to be proud of.

Football's peacemaking efforts did not stop with the deputy sheriffs of Millwall county. The players joined in, too, albeit with breathtaking hypocrisy in some cases.

Manchester United's Wayne Rooney asked why people would wreck their own community as he pleaded for calm via Twitter. Because Rooney has never pressed the self-destruct button close to home, has he?

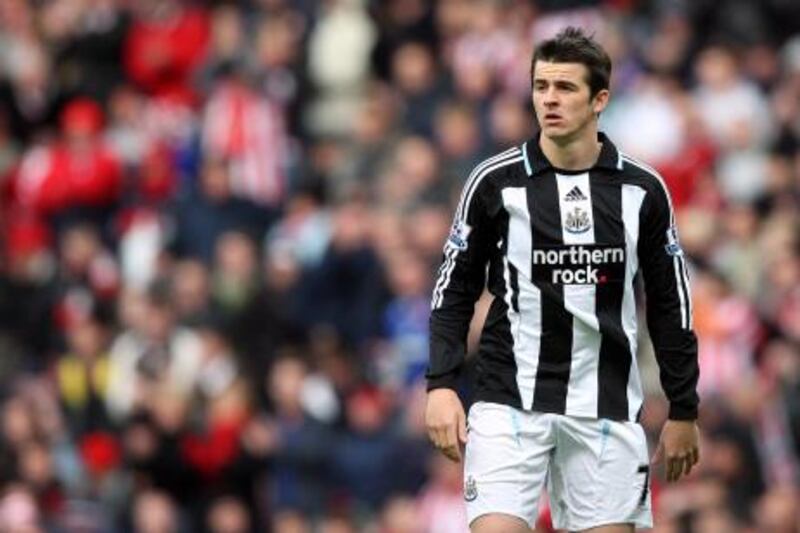

Joey Barton, Newcastle United's renowned pacifist, called for rioters to be educated and quoted the Dalai Lama: "You must not consider tolerance and patience to be signs of weakness, I consider them signs of strength." Tell that to the teenager he beat up outside McDonalds.

And Liverpool's Steven Gerrard, whose peacemaking skills were caught on CCTV during that bar brawl which landed him in court, appealed for an end to the violence in his home city.

When footballers are dishing out lectures in self-restraint, you know that society has changed.

As if to emphasise this reversal of fortune, football did not just clamour for calm but revelled in its new-found status as the victim, rather than the source, of mindless violence.

When Wednesday's match between England and Holland was cancelled due to safety fears, for example, the home players were wheeled out for a media photocall looking suitably crestfallen, even though they usually do everything they can to avoid friendlies.

And the Tottenham manager Harry Redknapp's response to the cancelling of today's match against Everton was equally emotional, with the loveable old duffer seeming to suggest that public disorder would not take place if young men wore blazers and trousers, not these new-fangled "jeans with their backsides hanging out".

Yes, all in all, football's PR men may consider this a great week for the game - a week in which it finally shed its violent past and stood on the side of the righteous. Britain may still be plagued by mindless yobs, they might think, but they are no longer our mindless yobs.

Frankly, I do not believe that football's hands are as clean as it would like to think. It may not spark the violence like it did in the past, but it has helped to fuel a seething class war between the haves and the have nots.

On Tuesday night, coincidentally the height of the violence, Sky Sports broadcast a self-congratulatory documentary marking 20 years since the conception of the Premier League.

The Night Football Changed Forever documented a slap-up meal, held in November 1991 and attended by various television and football executives, which saw an agreement that television income should no longer be shared equally across the 92 league clubs, but given mainly to the biggest clubs.

Some would say, correctly, that this was a major catalyst for the crushing of football hooliganism: the new image and cash flood enabled clubs to create safer stadiums and a better product that appealed to women, families and a better class of fan.

That transformation was undoubtedly a good thing. Hooliganism was dangerous, ugly and terrifying. However, let us not forget that the Premier League was founded on the cold, hard principle of selfishness.

Manchester United, Liverpool, Arsenal, Everton and Spurs did a deal to improve their lot at the expense of smaller clubs. It was a deal which priced poorer supporters, including the well-behaved ones, out of the game they loved.

It was a deal that saw players become separated from their communities, their spiralling wages taking them from the nicer suburbs of town into gated villas with private security guards.

It was a deal which encouraged foreign mercenaries to shuttle between clubs without loyalty.

It was a deal which enabled young heroes to flaunt obscene wealth via the cult of bling: supercars, designer labels and wads of cash.

It was a deal that sanitised the atmosphere of match days but helped to pollute our everyday culture into a ruthless celebration of wealth and power above all else, including a sense of community and respect. This week, England tasted the bitter fruits of that culture, and there is nothing football can do about it - apart from maybe posting a posse of Millwall fans on every street corner.

The Premier League is nearly 20 years old. Is it just coincidence, I wonder, that so were most of the looters.