Football in Egypt was once associated with joy and national pride, but since the 2011 popular uprising that toppled long-time president Hosni Mubarak, it has been an endless loop of violence and tragedy.

Champions of their continent seven times, Egypt have failed to qualify for the past three Africa Cup of Nations tournaments since winning their third successive title in 2010.

For two years between 2011-13, the country’s two most-storied clubs, Al Ahly and Zamalek – the 2010/11 Egyptian Premier League champions and runners-up – continued competing in the African Champions League because the domestic competition was twice abandoned abandoned owing to security concerns.

In post-revolution Egypt, the lines between sports, politics and religion have become even more blurred.

It did not take long for Bob Bradley, the American who took over as coach of the Egypt national team in 2011, to understand the situation.

“When you come here, you get a real sense of how football is part of all of this,” Bradley said at the time. “You realise how football and politics are totally connected.”

After the 2011 revolution, the Egyptian league had a two-and-a-half-month suspension before Ahly cruised to their 36th title.

The next season, on February 1, 2012, at the Port Said Stadium, the country witnessed one of the biggest disasters in its football history.

Read more: In Syria, football continues on as inspiriation, propaganda, shadow

After watching their side beat Al Ahly 3-1, fans of Al Masry, the home team, stormed the pitch armed with stones, knives and other weapons and attacked opposition fans, players and coaches.

Police reportedly just stood and watched, refusing to intervene or open gates to help supporters escape, as 72 people were killed and more than 500 injured.

Egyptian football has not been the same since. The league was suspended following the tragedy and on March 10, 2012, the authorities decided to cancel the remainder of the season.

The cancellation was a blow to the clubs, who had already had big financial losses because of the stoppages in 2011.

“Most football clubs would go out of business if they cancelled the league,” Khaled Mortagey, a member of the Ahly board told BBC Sport in 2011.

“It’s a very irresponsible decision from responsible people if they cancel the league, or postpone it even more.

“Not just the football clubs in Egypt could go bankrupt, but all the sports in Egypt because football is the main source of revenue to fund other sports.”

Manuel Jose, manager of Ahly during those turbulent times, echoed those sentiments on Ahly’s TV channel.

“Egyptian football is the best in Africa and we must save it from losing its superiority on the continent,” said the Portuguese, who had been attacked by the Masry fans in the Port Said riot.

“I ask the officials to resume the league’s activities as soon as possible because all the teams are severely affected by the current stoppage. Football in Egypt could collapse and the teams could go into bankruptcy if the situation remains as it is.”

Amid the growing financial woes and political uncertainty, the board members at the clubs started stepping down and unpaid foreign players and managers started packing their bags to leave.

At the time of the Port Said tragedy, Anwar Saleh, the acting chairman of the Egyptian Football Association (EFA), pleaded with the government to reverse their decision “because cancelling the league will have dire consequences on Egyptian football on all fronts”.

He said football “is a big business that employs more than four million people”.

“We’re the ones who are suffering the consequences of the football stoppage,” he said.

“We’re ready to take full responsibility for the sport that entertains tens of millions of fans and allows more than four million families to earn livings, families who have suffered greatly during the previous period. Football isn’t just a sport. Football is intimately related to politics, tourism, economy and industry.”

The Voice of Sportsmen, a newly formed group of football players, also added their voice to the growing calls for resumption of the league and said it was “extremely important that football competitions are resumed because this is our job and our sole source of income”.

“We would like to fully stress on our support for the rights of retribution for the Port Said martyrs,” they said.

“We want swift justice through the legal channels. But that has nothing to do with football resumption.”

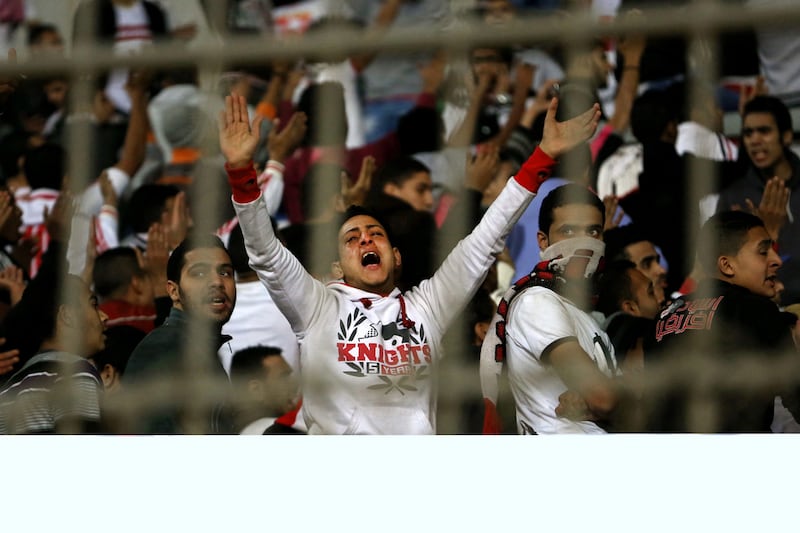

The Ultras Ahlawy, who along with hardcore fans of rival Cairo powerhouse Zamalek, the Ultras White Knights, played a crucial role in organising the 2011 protests at Tahrir Square that brought down Mubarak’s government.

They refused to budge, though, from their stance on the game and one of their leaders warned: “We will never let the football come back in Egypt unless the field is clean from corruption.”

Keeping to their promise, the Ultras Ahlawy stormed an Ahly training session just before the resumption of the league in February, 2013, and chided the players for their lack of support through a banner that read: “We followed you everywhere but in the hard times we didn’t find you.”

A month later, as a court upheld the death sentences of 21 of those arrested in connection with the Port Said riots, but acquitted seven police officers, the Ultras Ahlawy went on a rampage in Cairo, torching a school and a police club before storming the EFA headquarters, stealing its contents and setting the building on fire.

Riots erupted in Port Said as well and more than 40 people were killed in the two cities – there has been no end to the burning and looting and killings since.

This year, a week after the third anniversary of the Port Said massacre, more than 20 fans were killed as the ultras of Zamalek tried to force their way into the Air Force Stadium, where their team were to face Enppi.

Reports said the police opened fire after fans without tickets attempted to storm the stadium.

The violence did not lead to the cancellation of the match this time. It was delayed by an hour and finished 1-1.

That incident, however, was the final straw for the Egyptian authorities and in May, an urgent matters court decided to ban the activities of all ultras fan groups nationwide, accusing them of complicity in “riots” and vandalism.

This decision was pleasing to most fans, players and officials.

“The history of Egyptian football is lost and cannot be recovered,” an EFA official had remarked after the torching of the headquarters in 2013.

It had been a proud history, dating back to 2,500BC when the ancient Egyptians, according to historians, played a football-like game to celebrate the abundance of the earth.

There has not been much to celebrate in the country in recent times, but football, if allowed to continue uninterrupted, can change that.

History of Egyptian football

– If you believe the Egyptologists, football can trace its origins to ancient Egypt, where they played a football-like game during feasts of fertility. Balls made of linen have also been discovered in tombs that date from 2,500BC. The ancient Egyptians used to wrap the balls in bright-coloured cloth and kick them around the ground to celebrate the abundance of the earth.

– In modern times, the earliest mention of football in Egypt can be traced back to 1882, when the locals started playing matches against occupying British soldiers. In 1914, Al Ahly Sporting Club started organising matches between students and these games played a big role in spreading football across Egypt.

– By 1920, Egypt had a national team, which took part in the Olympic Games in Belgium, losing 2-1 to Italy in the opening round. Egypt did, however, beat Yugoslavia 4-2 to finish eighth.

– The Egyptian Football Association was founded a year later in 1921 and on May 21, 1923, they received Fifa affiliation.

– In 1934, Egypt became the first country from Africa and the Middle East to participate in a Fifa World Cup in Italy, but lost 4-2 to Hungary in the first round.

– In 1957, Egypt won the first of their seven Africa Cup of Nations titles.

arizvi@thenational.ae

Follow us on Twitter @NatSportUAE