One day nearly six years ago, a hazy, sleepy day in Faisalabad needed some rousing.

Faisalabad is not nearly as uneventful a city as many imagine and Iqbal Stadium is one venue in Pakistan where healthy attendances are almost guaranteed.

Nevertheless, the third day of the second Test between Pakistan and England needed a little poke.

England, fresh from a monumental Ashes triumph against Australia, had been gazumped in the first Test at Multan but were now fighting back through Ian Bell and Kevin Pietersen.

The pair had batted through the third morning at a pace that was healthy but in a manner altogether more attritional and cautious.

The surface was not helping and, as the afternoon sun skirmished with the clouds, already a draw was the widespread forecast.

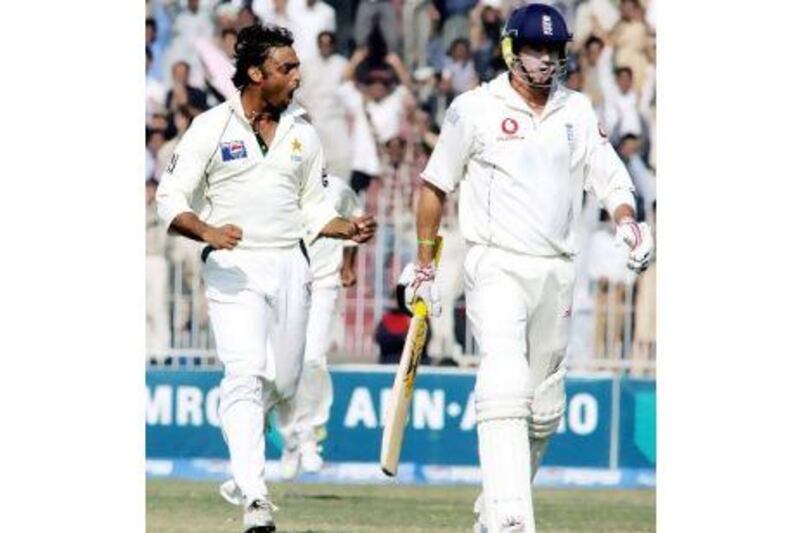

Seven overs after lunch, Shoaib Akhtar came on for his second spell of the day, with a ball that was 79 overs old.

Iqbal Stadium is a small, intimate ground and so, as he began to run in, there came a very clear sense that the crowd was stirring. And with good reason, for over the course of a five-over spell, he changed the mood and tempo of the session outright.

It was not just the two wickets he took, though Pietersen and Andrew Flintoff were big scalps. Every time he walked back to his mark, he urged the crowd to lift and they responded so that as he ran back in, he did so to a wall of noise (over a 30-yard run-up, that is some noise).

Each delivery carried with it a different direction the Test could take and almost every one in the mid-90s mph. Not for nothing, is he nicknamed "Rawalpindi Express".

As with all Akhtar spells, each ball also felt like his last, as if the bandages holding him together would suddenly burst open to let him fall to pieces.

That is what made watching him so compelling, that for so long, every time he strained - and he always did strain for more pace - he knew, we knew, it could be the last time.

There is the nobility of a martyr in that.

The spell comes to mind not because of the headlines Akhtar generated recently (surely the most pointless of the countless tangles Pakistan and India get into). It does because of a gathering last month arranged by the Lord's Taverners in London of some of the game's greatest living fast bowlers.

The get-together was a celebration foremost. But it was equally a reminder of how bereft the modern game is of quality fast bowling.

There are exceptions.

It says something about England's pace attack that watching them has become compulsory; this, after all, is a side in which Jonathon Trott and Alastair Cook regularly bat together for days. Dale Steyn and Zaheer Khan are always worth watching, but who else? These are dark, barren times for fast bowling.

They are a vitally important breed. It is one off the many reasons, one is why I - and perhaps many others - started watching cricket.

The game does not immediately appear, especially to the outsider, an overtly taxing one physically. Those who do not follow suspect it to be soft, where players such as David Boon, Inzamam-ul-Haq and VVS Laxman - none ever to be mistaken for a top-class athlete - can prosper.

This assessment is neither fair nor entirely accurate and the modern game places greater demands on fitness. But fast bowlers are what have always made cricket a truly physical, athletic pursuit.

You could watch a batsman bat for hours and imagine yourself doing that; you don't need to run and in fact it helps if you mostly stay still until you need to move.

But fast bowling? Sprinting in 30 metres, six times in a couple of minutes, putting your body through entirely unnatural motion to hurl a ball at the greatest speed your shoulders, arms, wrists and entire upper body can coordinate, all that stress on the back, knees and ankles?

This contains the rawness, the athleticism and notions of the intense physical labour that every major sport needs to feel comfortable calling itself a major sport, the kind that puts the top level outside the grasp of those watching.

And when it comes together, as it did with the Akhtar spell, as it has done countless times over so many years, the game is the most alive it can ever hope to be.

It is only a bonus that fast bowlers have always made for the best characters.

The present dearth owes itself to many factors, all much heard and all feeling like part of an continuing sanitisation of the game.

Pitches around the world are blander and slower, batsmen - with more protective gear and fewer bouncers to worry about - increasingly empowered.

Three formats of the game and an unending calendar take heavier tolls so that wary fast bowlers rarely come at full tilt. Some have been over-coached so that they can't.

The shortest, most popular format has further reduced them to become run savers.

The yorker is no longer a wicket-taking ball as much as it is one that simply cannot be hit to the boundary. Before Twenty20s, slower balls used to take wickets on surprise, not be bowled five times an over by Lasith Malinga so that conceding eight runs is a good result.

Fast bowlers used to be the game's edge, sharp and jagged.

Sadly, as those who gathered at the Lord's Taverner must already know, they are being smoothed out.

osamiuddin@thenational.ae

Follow The National Sport on @SprtNationalUAE & Osman Samiuddin on @OsmanSamiuddin

Bowlers with raw pace fast on decline

The present dearth of fast bowlers owes itself to many factors, all much heard and all feeling like part of an continuing sanitisation of the game.

Editor's picks

More from the national