While Declan Hill went around Asia researching match fixing in football, he had an unusual bedtime routine. "Each night before I went to bed," he writes in his stunning yet mostly ignored book The Fix: Soccer and Organised Crime, "I would carefully unscrew the light bulb in my hotel room, rearrange the furniture, and put my bed in a different position."

The logic was that if anyone broke into the room aiming to kill him, the dresser in front of the door and the lack of light would give Hill a few extra seconds to act. "It changed the odds in my favour just a little," he said. The Canadian journalist-cum-Oxford sociologist is an expert on betting odds and how to change them. His quarry is the mostly ethnic Chinese men who fix football matches - including, Hill convincingly argues, matches at World Cups.

This book changes the way you think about football. However, it seems unlikely to change the odds against the match-fixers. Quite the contrary: they have gone global. Hill is a Quaker, and he writes with the mix of education and moral conscience peculiar to that small Christian sect. He is an outsider to football, which is probably an advantage. His particular drug is not the game itself but investigative journalism.

Hill's journey begins in Malaysia and Singapore. If England is the home of football, then the Malay Peninsula is the home of match fixing. A Malaysian known as the "Short Man" was implicated in the trial of Bruce Grobbelaar, the former Liverpool goalkeeper, for throwing games in the mid-1990s. Grobbelaar was eventually cleared of all allegations. And from confessions of alleged match-fixing suspects that Hill says Malaysian police let him see, he details a sort of master tutorial by a leading player on how to fix matches without spectators or even coaches noticing. Hill combines this information with his own interviews, and statistical methods that he learned at Oxford, to draw up some basic rules of match fixing:

After comparing "130 football matches that were known beyond legal doubt to have been fixed" with a control group of honest matches, Hill found fixed matches average 20 per cent more goals than honest games. The surplus is overwhelmingly scored in the first 10 minutes. After that, the desired result assured, everybody takes a rest. √ Own goals are scored "in just under 20 per cent of fixed matches", compared to only 10 per cent of honest games.

√ Bent referees are twice as likely to give penalties as honest ones. √ Fixed goalkeepers should charge out of goal frequently, to help the opposition score. One player told Hill: "Playing a stupid offside. That was probably the best one. You go charging up the field to play an offside and the forward goes charging through." Fixing matches in Asia was fairly easy, he found, as footballers there are not paid much. The link between low pay and bribery is as strong in football as in all spheres of life. Michel Platini, the president of Uefa, the European football association, said last September that match fixing "doesn't touch big matches. It touches little ones. If it happens in Germany, it was in the second, third or fourth division. It's not in the big matches, not in the Champions League, in things like that."

Indeed, Hill trots us through an historical survey of match fixing that locates the problem in underpaid leagues: England in the 1950s and 1960s, Finland and Belgium more recently. A player in an eastern European team e-mails Hill's researcher an offer to tell him about a fixed match in advance for ?200 euros (Dh906), so that the researcher can bet on it. The match result turns out as the player predicts. At this point there is the temptation to shrug and say, "Well, I'm not a great aficionado of the eastern European leagues. As long as the more important games are honest, I'm happy."

The problem is that most footballers in the world are underpaid relative to the unprecedented cascades of money being bet on football. In many countries, people can now go online and use a credit card to bet on games being played almost anywhere, even in Iceland or Scottish junior leagues. Hill quotes "a recent study for the American journal Foreign Policy [that] estimated the entire Asian gambling industry, both legal and illegal, at $450 billion [Dh1,652bn] a year." That is four times the size of the Asian pharmaceutical industry.

True, a Manchester United-Chelsea match will not be fixed - multi-millionaire players can afford a sense of honour - but it would be foolish to be as certain about an Eastern European team playing a top English team in a group game in the Champions League. Even at World Cups, perhaps a quarter of players are not millionaires. This is where the opportunities for match-fixers are. Hill knows, because he has met them. "Pal", a South East Asian fixer down on his luck, reminisces to him about allegedly bribing an African team at the World Cups of 1994 and 1998. As well as paying cash, Pal flew to the African country and arranged for water pipes to be laid to the middleman's village. Hill does not necessarily believe him, but thinks the story credible enough to put on the public record.

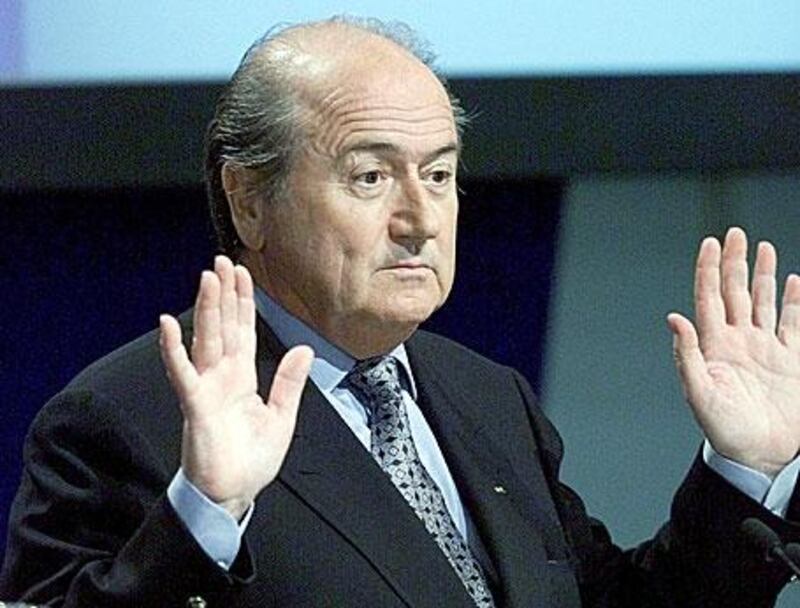

In Thailand, a match-fixer whom Hill calls "Chin" - names are changed to protect the guilty - summons him late at night to a room in a country club outside Bangkok. It is like a scene from Hitchcock. Hill arrives, petrified. Happily, Chin does not shoot him, but instead unfolds his plans to fix the World Cup in Germany. Naturally Hill wonders why Chin is telling him this. After all, match-fixers are in the business of creating fantasy. Anyone wanting to discredit Hill's book - and Sepp Blatter, the president of Fifa, the global football authority, wants exactly that - would start by attacking the credibility of the fixers' testimony. Hill has a stab at analysing their motives. Both Chin and Pal hope he will write a book about them, even though he explains it would not net them much money and might interfere with their core business. He explains that these men are masters of what they do, proud of their skill and anxious for wider recognition.

Match-fixers, like everyone else, seem to yearn to be heard. They also know that even if they talk, the risk of being caught is slim. Hill recounts countless stories of police investigations of match fixing that tail off into nothingness when confronted with the immensity of Asia and the power of its gangs. And his belief in Chin's story grows when Chin lets him sit in on a preliminary meeting to fix a World Cup match.

"There were four men. They sat at a little table hunched over so they could hear one another while they spoke." Hill was sitting at the next table, desperately trying to listen in. One of the quartet is an African. Hill takes a grainy photo of him with a hidden camera. Weeks later he flies to the World Cup. During the tournament, he and Chin speak on the phone, and the fixer predicts the outcome of four matches, three of them accurately, down to the margin of victory. (Match-fixers bet not simply on victory or defeat but on the margin of victory.)

All this is intriguing but hardly proof. After all, none of the results was exactly unexpected. (Hill shows that match-fixers often arrange for favourites to beat underdogs by a certain margin, partly because that allows them to bet the same way as most ordinary punters, thus avoiding the suspicion that would arise if they staked fortunes on an improbable outcome.) There would seem to be enough evidence for the football authorities to investigate. They have not. It was suggested to Hill, on his way to yet another airport, that the revelations in his book had changed nothing. He laughed: "Absolutely right. Nothing is being done about it. It's a gang of criminals. It should be very easy to spot."

This big book has made a splash only in a few countries. "It's been on the top 10 best-seller list in Germany, France and Canada, and I think in Denmark," Hill says. However, it is not out in Britain, presumably because of the country's stern libel laws. Mostly, Hill thinks, football and its fans just do not want to know. In the book, with some difficulty, he finds the obscure courtroom in Frankfurt where a match-fixing trial is taking place. (The suspect, a Malaysian Chinese, will escape Germany before any verdict can be reached.) There are only two other spectators, one of them, he claims, a lawyer from the German football association. Hill tells him who he is, tells him that the fixers on trial here may also have infiltrated the Bundesliga, and offers to provide information. "The lawyer's response? He ran away. He disappeared out of the court, past the security scanner, and out the door waving his battered briefcase at me as if to ward off any more knowledge."

All football fans are tempted to suspend their disbelief and keep enjoying the game. As Blatter tells him: "If you are right, it hurts." Yet Hill warns that football could eventually collapse worldwide. At least Uefa is beefing up its efforts. It has just hired four more people for its "disciplinary" team, two of them full-timers. Platini asks, "How do you want us to function, if there are only two people on the disciplinary side?" Sadly, the problem may be too vast even for two new full-timers to solve.

Last August, after Hill had finished his book, two Chinese students, Zhen Xing Yang and his girlfriend, Xi Zhou, were found dead and mutilated in their flat in Newcastle, England. Even their cat had been drowned. The Daily Telegraph in Britain reported: "Internet users on UK-based Mandarin websites have identified Mr Yang as a recruitment agent for a gambling racket which relied on the results of live Premier League football games being shown a couple of minutes later in China to beat the bookmakers." Guang Hui Cao, a Chinese man living near Newcastle, has been charged with the Newcastle murders and is in custody. A trial has tentatively been set for June. But whatever comes out in court, do not expect it to do any damage to match fixing. As Declan Hill's brave book shows, this is now a mature, stable and global industry. @Email:sports@thenational.ae

September 25, 2009 - Uefa probe 40 fixtures, which are among the 200 games being investigated by German football authorities. November 20, 2009 - Police across Europe arrest 17 people as part of an investigation into a match-fixing ring which affected up to 200 games, including some in the Champions League. November 25, 2009 - Uefa name five clubs suspected of involvement in rigging seven European games: Albania's KF Tirana and KS Vllaznia, FC Dinaburg of Latvia, NK IB Ljubljana of Slovenia and Hungary's Budapest Honved. December 3, 2009 - The Spanish football federation announce that about 300 players are under investigation for possible involvement in a match-fixing scandal. December 22, 2009 - The German football federation suspend an assistant referee, Cetin Sevinc, suspected of involvement in match fixing December 31, 2009 - China launches a clampdown on match fixing and corruption with the arrests of more than 20 sports officials. January 22, 2010 - Nan Yong, China's top official, is sacked after being questioned by police as part of an investigation into match fixing. February 23 - The Sheffield United-owned Chengdu Blades are relegated from China's top flight for match fixing. March 17 - Chinese police arrest three football referees on suspicion of match fixing, including one official who presided at the 2002 World Cup. April 27 - Thanasis Plevris, a Greek politician, reveals the names of five Greek Super League sides mentioned in a Uefa match-fixing report: Panthrakikos, PAS Giannena, Panionios, Atromitos and Kavala. May 6 - Five footballers are arrested in Hong Kong over allegations of match fixing.