Legend. Most agree it a term overused when describing sports stars.

But not when it is applied to the name Jonah Lomu, unquestionably the first superstar of rugby union, who died unexpectedly after arriving back in New Zealand with his family from Dubai on Tuesday.

He was 40.

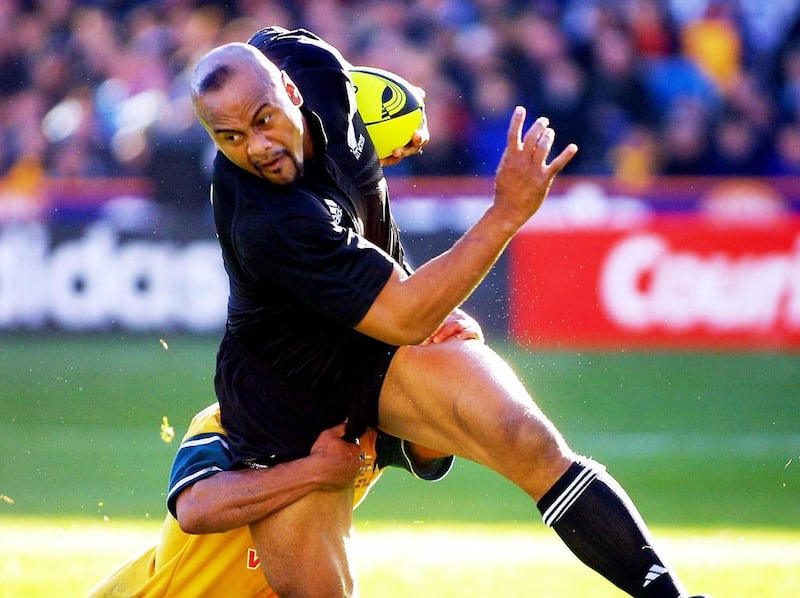

The former New Zealand winger, whose coruscating runs and imposing physique revolutionised the oval-ball game, had suffered health problems for decades and battled a rare kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, that brought an end to his career all too prematurely in 2007.

It is hard to think of any sportsperson making as seismic an impact on their sport as Lomu did at the 1995 Rugby World Cup, both off and on the pitch.

Although New Zealand would go on ultimately to lose the final to hosts South Africa, Lomu’s seven tournament tries, including four in the pulverisation of England in the semi-final, will live long in the memory.

The All Blacks arrived at that World Cup, as they invariably do, as heavy favourites to win the tournament.

READ MORE:

[ A sporting hero and a special person: Tributes pour in for All Blacks legend Jonah Lomu ]

[ Jonah Lomu: Rugby’s first global superstar who drove his sport into a new era ]

Their squad was packed with rugby royalty: Zinzan and Robin Brooke, Justin Marshall, Andrew Merthens, Frank Bunce, Walter Little, Ian Jones, Sean Fitzpatrick, the list went on. Also included was a little-known, Auckland-born winger with just two caps to his name who, over the course of the tournament, would not only redefine the role of a winger from fleet-footed whippet to blockbusting bulldozer, but turn rugby’s appeal to a broader, worldwide audience and give the sport its final shunt over the line from amateur to professional status.

Lomu announced his arrival in some style. Ireland’s players could have been forgiven for asking “Jonah who?” when lined up against a formidable All Blacks team in their opening pool game boasting some of the world’s best players.

By the end of the match, the whole world knew the name of the 1.96 metre, 120 kilogram hulk occupying the New Zealand wing after he gave the first glimpse of his brutal running game with two tries.

After negotiating the rest of their pool with ease, New Zealand faced Scotland in a tough quarter-final, but ultimately prevailed with Lomu running in another try and punching holes in a hitherto solid defence.

Then came that semi-final against England at Newlands.

If barnstorming through Scottish brothers Scott and Gavin Hastings was regarded as evidence of Lomu’s prowess his pulverisation of the English defensive axis of Rob Andrew, Will Carling, Jerry Guscott and Mike Catt, as, well as his opposite number Tony Underwood, was something rarely witnessed before or since.

Lomu, who, have I forgot to mention was just 20, simply destroyed England, running in four, brutal tries. There was simply no stopping him. Lomu showed his repertoire in going past players – that is around, through and over them – and the sight of Catt rolling backwards after attempting to halt the Lomu juggernaut as he thundered towards the England try line still makes for uncomfortable viewing.

That effort was recently voted the greatest try in the tournament’s history.

New Zealand would lose the final in extra time to South Africa, the enduring image the sight of president Nelson Mandela presenting Francois Pienaar with the Webb Ellis Cup while donning the Springboks captain’s No 6 jersey; a new dawn in the country’s dark history.

While I would never try to dampen the romance of that image, for me, the sight of wunderkind Lomu in full flight will leave a longer lasting impression. It is a travesty he would finish the tournament with seven tries but no winner’s medal; a Herculean defensive effort from Japie Mulder and Joost van der Westhuizen providing the answer to the tournament’s toughest question: How do you stop Lomu?

By today’s standards, Lomu’s size on the wing would have been less obvious, but during the 1995 tournament he looked the living embodiment of every defender’s worst nightmare. With speed, lots and lots of speed. A phenom.

Because of his bulk, one tactic the All Blacks would often employ whenever presented with an attacking scrum was to remove Zinzan Brooke – a brute of a No 8 if ever there was one – and deploy Lomu at the base of the scrum to give his forwards more oomph to get the ball over the line. That’s how strong he was.

It speaks of how highly the New Zealand forwards rated him – name me another pack in world rugby that would welcome a back into their domain to give them extra power come crunch time.

But for all of his menace, the sense of impending doom whenever he had ball in hand, the sinister look at an opposition player with designs on stopping him, there was a softness to Lomu; a smile that could light up both New Zealand’s North and South islands; a gentle giant, if you will forgive me this one terrible pun.

While overcoming obstacles during a 63-Test career that yielded 37 international tries was rarely an issue, his health problems off it presented its own set of challenges.

Lomu underwent a kidney transplant in 2004 and had been on dialysis treatment for the past 10 years. He was on a waiting list for a kidney transplant when he died, his previous one having failed in 2011.

Lomu was still a regular on the rugby scene up till his death and had been at the recent Rugby World Cup in England on promotion work. Friends and fellow journalists describe him at one function as “affable”, “pure gold” and “lovely” and, generally, in good health.

One picture circulating on social media on Wednesday showed Lomu touching down in New Zealand wheeling what looked like 20 suitcases on one trolley through the airport. Why pay four porters to do a job when one man can do it himself?

Which makes the news of his passing even more harder to come to terms with. As recently as Monday, he tweeted pictures of him and his family at various Dubai landmarks, where they had stayed on a short break on route back to New Zealand. He looked happy; he always did.

Legend. Sometimes, it is a word not used nearly enough.

All Black great Lomu would pulverise defences but always make time for the fans

The news of Jonah Lomu’s death hit me like as if the big man was running at me full pelt during his pomp. I had just been woken up by my two young sons when I read the news on my phone. My first thoughts were for his family, and in particular his young sons Brayley, 6, and Dhyreille, 5, who have lost their father.

It is hard to mirror the image of a Lomu suffering with poor health with the coruscating and rampaging player who terrorised defences for what now feels an-all-too-brief period for the All Blacks between 1995-2002.

I was 17 when I first saw him play in the flesh; a pulsating encounter on a brutally cold Saturday afternoon at Twickenham, when the All Blacks clawed back a seemingly unassaible 23-9 deficit to draw the game 26-26.

It was the final match of a long, unbeaten tour for the New Zealand squad, who could have been forgiven for wanting to get to the changing rooms, pack their bags and head home on the long flight to their loved ones. But Lomu, indeed all of the All Blacks, to be fair to them, braved the cold for up to an hour to speak with their legion of fans, both Kiwi and English, and signed every autograph and smiled for every picture.

Despite the galaxy of stars, which included Andrew Merthens, Zinzan Brooke and Walter Little, everyone, including this star-struck fan, was only after one autograph and their picture taken with one All Black.

Lomu obliged everyone.

His impact on rugby fans worldwide can never be overstated. Hopefully, one day, that thought will be of some small comfort to his sons.

sluckings@thenational.ae