Ian Hawkey tells the story of how the beautiful game helped Algeria gain their independence His real name was Hocine Dihimi, but almost everybody who watched football in Algeria in his heyday knew him simply as Yamaha. Some say it was because he lived near a moped repair shop, some because he buzzed around. He would beguile visitors from abroad with his circus acts during matches of the Desert Foxes, the Algeria national team, and games involving his club, Belcourt.

He was a cheerleader almost as widely recognised as the top players of the time, and his time coincided with of some of the country's genuine greats, footballers like Rabah Madjer and Lakhdar Belloumi. Yamaha was a clown and a trickster. Agile at climbing whatever barricades separated fans from players, or the mass of supporters from VIPs, his catch-me-if-you-can chases with the police along the running-track at the huge Fifth of July stadium became part of the theatre, the whipped-up atmosphere.

Yamaha was said to have changed the way football was watched in Algeria, to have come up with the idea of bringing a saxophonist in to accompany the percussion of darbuka drums. He was liked by the players, travelled with the national team as if a mascot, chanting, jiving, a frenetic court jester, with a mobile face and a mouth so wide he could apparently hide his whole fist in it. When he left the scene, El Watan newspaper called Yamaha 'a national figure, famous for the joy he mobilised in big crowds and around football. He was a symbol without knowing it, a symbol of a youth that wants to enjoy life, a vivaciousness that has grown thanks to football.'

That was the mid-1990s. Algerians have had to bear some hard times since. But tomorrow evening, events in Blida could restore some of the spirit of the late Yamaha. Algeria meet Zambia in qualifying for the 2010 World Cup. They already hold a three-point lead over the Zambians and over the African champions, Egypt. Two more wins from their remaining three games would very likely take the Desert Foxes to the finals in South Africa.

They would feel they belonged there. Few nations have had such dramatic impact on the story of football in Africa or across the Arabic-speaking world. Just ask Mohammed Maouche, a septuagenarian whose commitment to his country's football once sentenced him to a year in a French prison. He has quite a story to tell. Maouche's peak as a player coincided with Algeria's ghastly war of independence from France and he became a ring-leader in recruiting a group of equally gifted footballers to join the political struggle.

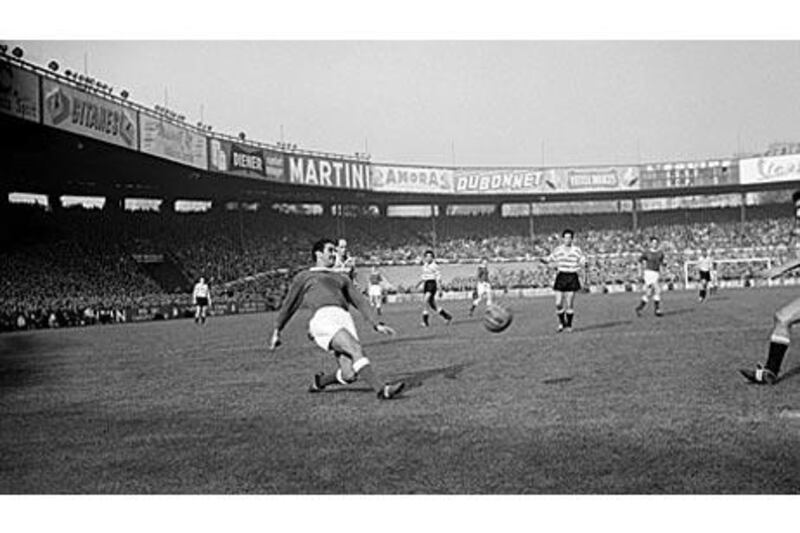

The principle was simple, the risks large. By the mid 1950s, some of the most conspicuous Algerians in France were sportsmen. Maouche was typical, a 20-year-old spotted playing as a skilful inside forward in Bologhine, he joined France's Stade de Reims, who within months of his arrival had reached the first final of the European Cup. By the end of his first full season in France he had been selected for the French military team, one upside of the stipulation that all Algerian men on the French mainland do French national service. Maouche won the world military champion ship with France, along with his compatriot and contemporary, the dazzling No 10 Rachid Mekhloufi, a star of the French champions, Saint-Etienne.

In early 1958 the pair would be among four Algerians shortlisted for France's squad to go to the World Cup in Sweden. On the one hand they felt flattered, on the other they could not live entirely divorced from their experiences as immigrants whose families lived an edgy and dangerous day-to-day existence in North Africa where torture had become routine. "You sometimes did not know who your enemies were," Maouche says of the culture of suspicion, in which informants, militias, French soldiers, activists all struggled for control of a country.

"It was a horrible time in Algeria. We were all oppressed by it." Football, they gradually decided, could liberate them. By 1958, several Algerians playing in the French championnat had the idea of a wholesale defection put to them, the idea that a team of Algerian professionals would exit France over a weekend, gather at the headquarters of the Front Liberation National (FLN), the guerrilla army fighting for independence, in Tunisia and launch an 'illegal' national team as part of Algeria's nation-in-waiting.

There was much to give up. Freedom, for a start: those, like Maouche, who were still doing their compulsory French military service, albeit as sportsmen, faced charges of desertion, and arrest. Then there was wealth: Mohammed Zitouni, the France international, earned a handsome salary at Monaco and had been the subject of a lavish bid by Real Madrid. The prominent players each gave their OKs to the daring scheme. They selected the weekend of April 13-14 1958 for the grand exodus.

France were due to play a friendly against Switzerland a few days later and Zitouni, committed to turning his back on Les Bleus, was pencilled in for France's starting XI. His absence when the French squad gathered would be conspicuous and guarantee immediate impact and resonance. The fixture list for the championnat that Saturday and Sunday also offered some favourable combinations of where the Algerians preparing for their secret exits across the Swiss and Italian borders would be designated to play.

"It was very, very serious in the planning. Every detail was studied," recalls Maouche. "We didn't have big meetings about it, talks were almost always individual-to-individual. Of course there was a list, but hardly anybody knew all the other names that might be on it. It was all very secret. We had to reduce all the possible risks, but of course, there was no zero-risk." The first of the defectors slipped out of France on the Friday night. But on the Saturday some plans went awry and connections were missed.

Maouche, off duty from Reims that Saturday, had been due to rendezvous with a cadre of players in Switzerland early on the Monday. Tall and upright, his dark hair brushed back, he entered the first-class waiting room at Lausanne station at 7am, looking every bit the privileged student or young professional. He waited. And waited. His accomplices never showed. Concerned and cut off, Maouche decided to return to Paris, where he could contact some of the organisers to find out what had happened.

Barely had he disembarked the train in the French capital than he knew his own participation was now in serious jeopardy. "When I got to the station at Paris, that's when I saw the newspaper front pages," he says. "L'Équipe had a huge headline saying that nine Algerian players had disappeared, and that Maouche of Reims was missing." Later that day he was arrested. "The first three days in the cell were hard. There was an especially vicious gendarme involved, very racist towards Algerians. I was badly beaten," he says. But the majority did make it to Tunis.

The coup had succeeded. A statement was issued from the FLN in Tunis announcing the arrival of the first footballers and declaring they had "answered the call to arms. As long as France wages a merciless war against their people and their nation, they now refuse to contribute their important and appreciated work to French sport. Like all Algerians, they have to suffer in the rapidly developing racist, anti-African and anti-Muslim climate".

This renegade team proudly played in shirts with the star and crescent embroidered on their chests, the Algeria flag hung over the venues they performed at, and they stood in line to the stirring sound of the Qassaman, a national anthem-in-waiting. Fifa did not recognise the FLN team, and threatened others who took the field against them. They found friends not only in North Africa - where they routinely beat Moroccan and Tunisian sides - but on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

By the late 1950s, they were inundated with invitations. They travelled to an enthusiastic Middle East. In Baghdad, they were serenaded by the Iraqi public with chants of "Vive Algeria, down with De Gaulle!". In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh made a point of comparing the colonial experience there with the French grip on North Africa "We were the true ambassadors of Algerian independence," reflects Maouche, who after a year incarcerated set about assembling more recruits and finally joining up with the FLN team himself.

"We all had a sense we were carrying the flag for our country and our continent. I would sit across the table with people and talk about the amalgam of people that make up Africa." They provided a sporting master-class too. In Mao's China the FLN Team gave coaching clinics to mass audiences. In Yugoslavia the FLN Team gained the sobriquet Brown Diamonds. When they took on the Yugoslav Olympic side, essentially the country's national team, 80,000 watched Mekhloufi lead a dazzling 6-1 deconstruction of the opposition.

They played 91 matches in four years, and won 65 of them. Algeria celebrated their independence on July 5, 1962. Those who had fought for sovereignty for the FLN abandoned their fatigues to return to civilian life. They remain heroes, even half a century on. Maouche and Mekhloufi would have a big influence on the next great generation of players, too. Come the 1982 World Cup, both had roles coaching and managing a team featuring Mustapha Dahleb, as celebrated in the French league of the 1970s as Mekhloufi had been in the 1950s, Madjer, Belloumi and the dashing winger Salah Assad.

These Algerians knew they were good - "We knew we had footballers who were strong on the ball, great dribblers," recalls Assad - but the world was stunned to see just how good they were. The opening game of their tournament was a sensation. They beat West Germany 2-1. After that came the anti-climax, they lost to Austria 2-0,to leave the group in a state of delicate poise, Austria on four points, West Germany and Algeria on two each - three points for a win had not been introduced at that stage - with Chile bottom of the table, having lost twice.

The West Germans held a superior goal difference. Then there was the ominous scheduling: on Thursday June 24, Algeria were to play Chile in Oviedo. Austria-Germany had been timetabled for the following afternoon in Gijon. In other words, the two European teams would know what maths would guarantee their progress. There followed an epic among World Cup scandals, now known as anschluss, with Algeria the victims.

The Desert Foxes' 3-2 victory left them with a goal difference of zero, one worse than Austria. What then happened on the Friday reeked. West Germany needed to beat Austria to go through: Austria could afford to lose by up to two goals and still join the Germans in the second round at Algeria's expense. West Germany scored after 10 minutes. From that point, all pace and urgency would be sucked from the contest as if by a giant syringe, the teams conspiring to keep the score at 1-0.

As the contest became more and more torpid, the crowd turned agitated. Algerians there waved peseta banknotes at the players. Even German television called it "the most shameful day in the history of our Football Federation". The Algerian Federation lodged a complaint with Fifa, in vain. Curiously, those who took the blow with most stoicism were the Algerian players. "Frankly we knew we were going home. We assumed Austria and West Germany would do what suited them both. They're neighbours. We all knew we should have made it harder for them anyway by playing better against Austria and beating Chile by more goals," recalls Assad.

After the adventures in Spain Madjer and Assad launched careers with leading clubs in Europe. Madjer joined Porto and scored, with a back heel, the winning goal in a European Cup final. Assad moved to Paris Saint-Germain. And in 1986 Algeria became the first Africans to qualify for successive World Cups. "We were an even better team than in 1982," claims Assad. "We ought to have waltzed into the second round with cigars in our hands."

There were to be no repeat heroics. Losing to Brazil and Spain in the first phase meant they went home early, the squad riven by tensions between some of the footballers who earned their living in Europe and those based in Algeria and rows about money with the Federation. Algeria became African champions, at home, in 1990, but the period after that was mostly downhill. The country became tense and dangerous as animosity escalated between the Front Islamique de Salud (FIS) movement and an iron-fisted government. Football was directly affected. Club directors became targets of assassinations.

Salah Assad spent four years in prison for his perceived sympathy with the FIS - "I was never charged, never believed in violence but simply practised my religion," he says now - and one day in 1995, little Yahama, the great entertainer of the arenas, was shot dead in his home district of Belcourt, some alleged by religious extremists. The atmosphere is better now in Algeria, though still some way from perfect. And the national team is at its highest point for nearly 20 years.

Up in Ben Aknoun, Mohammed Maouche is hopeful the Desert Foxes will again have a prominent place in the history of African football. "We have some good players, and a bit of spirit now," he says. "It would be very nice to part of the first World Cup in Africa." ihawkey@thenational.ae