It is a name that conjures up wildly different images in English sport: Wimbledon. It is where genteel Britain buys its strawberries and cream for a fortnight every summer, where the world's leading tennis players converge for the welcome anachronism of a tournament on grass.

Yet the south-west London suburb gave its name to a football club that was almost its polar opposite, the rough-and-ready outsiders who delighted in denting reputations.

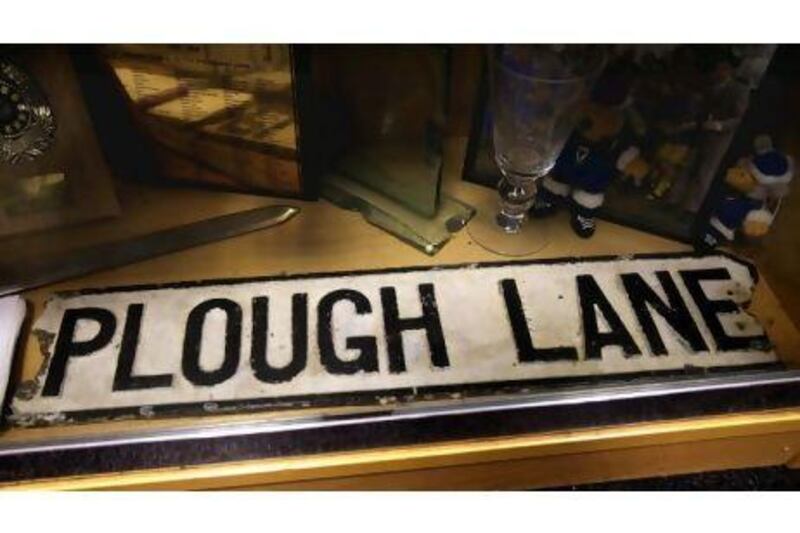

They were the Crazy Gang, the team whose blend of direct football and practical jokes enabled them to go from non-league to top flight in nine years, to survive for 14 seasons among the elite and to win the FA Cup in 1988. Neither a comparatively small fan base nor, for years, the absence of their own ground, after Plough Lane was closed in 1991, proved an impediment to the underdogs.

Now there is a third Wimbledon, lending a very different perspective: AFC Wimbledon. It is both the start of a trend, with FC United and AFC Liverpool following their lead, and unique. Widely regarded as the consequence of a club that was stolen from its fans and moved some 56 miles to Milton Keynes, the truth is, as ever, more complicated: as far ago as 1979, Ron Noades, then Wimbledon's owner, bought the now defunct Milton Keynes City with a view to a merger. Nevertheless, the concept of moving a club to a different town is novel in English football.

The franchise model is common in the US - explaining why a side with the suffix of Lakers can play in Los Angeles - but anathema in England until, in 2002, two years after relegation from the Premier League, the decision was made: Wimbledon would be relocated to Buckinghamshire.

Milton Keynes, the most prominent of the new towns that sprung up after the Second World War, was the biggest place in England without a Football League club. The solution created uproar. Now in the play-off places in League One, the third tier, MK Dons - the nickname taken from its forebears - has a new identity.

Wimbledon, under that name, played their last game in 2004, nine months after the move to Milton Keynes. But the story didn't end there. The hard core of the club's defiant fans ensured it wouldn't.

In 2002, around 3,500 formed AFC Wimbledon, the disenfranchised transferring their allegiance to leave the loftier club with a handful of supporters for their last year in London.

In their place, what emerged was a people's club. They held trials on Wimbledon Common, a local park, to recruit unattached players. A crowd of 4,657 turned up for their first game and, after groundsharing with Kingstonian at the latter's Kingsmeadow Stadium, AFC Wimbledon soon raised more than £1 million (Dh5.9m) to buy the ground outright.

Yet the new club faced other obstacles. They began in the Combined Counties League, nine divisions below the Premier League. They have now scaled the non-league pyramid and sit level on points with Crawley Town at the top of the Blue Square Premier League (four levels below the Premier). Either via the play-offs or the one automatic promotion place, a future in the Football League could beckon next season.

AFC's supporters include many of the architects of the original Wimbledon's glory days. Bobby Gould, their FA Cup-winning manager, said: "I always referred to our team as a ragbag-and-bobtail outfit. We were the street urchins of the game but had the strength to beat up princes. But what is happening here with AFC is just as remarkable, if not more so. They really started from nothing, in a park.

"They have shown what can still be done in football if everybody bands together. Spirit and determination can take you a very long way. And despite how much money dictates now, I really can see them rising up the Football League because like we did they have a special DNA. "

Gould is not alone in admiring the club he sees as the rightful successors to the old Wimbledon. Vinnie Jones, the midfield enforcer turned Hollywood hardman, has donated his FA Cup winner's medal. In a bid for acceptance from supporters of other clubs, who had dubbed them "Franchise FC", MK Dons returned the mementoes of the original club to the London borough of Merton.

Thus far, however, there have been marked differences between Wimbledons new and old. A club that acquired unwanted renown for its small gates - the lowest ever Premier League attendance was 3,039 when Wimbledon hosted Everton in 1993 - has been replaced by a genuine grassroots movement which has enabled AFC to become something of a glamour club at their level.

Michael Woolner, who joined AFC in their second season, said: "I had been playing for Hendon – a club of the same sort level – but jumped at the chance of being part of the new Wimbledon. Even if at that time AFC were still low down the non-league ladder. But the club was obviously on the way up and were playing in front 4,000 fans in home games. In comparison, you could be playing in front of 400 with a club like Hendon.

"Since my background was county football [the 10th tier of English football], it was a dream move for me even if fitting in my day job as an electrician and a lot of travelling to play and training was very exhausting.

"But at my level it was the best club I was ever going to play for. In a sense it was in way a bit like joining Manchester United at that level. And because the fans were so much part of the club the pressure to succeed was quite intense and the expectations very high."

Wimbledon were Premier League paupers a decade and a half ago, but AFC have become big spenders.

Woolner added: "When I was there I was only being paid £200 a week plus, say, £10-a-point bonus. But the club did have financial muscle and at the time were able to take players on loan from the Conference. Some of could have been on as much as £1,000 a week. So, as much as the club has risen from nothing, part of the rise has been down to economic muscle."

Dave Bassett's team accelerated through the divisions in the 1980s. Wally Downes, a Wimbledon player then and West Ham's assistant manager now, believes a repeat is possible.

"As we proved, nothing is impossible. What the club achieved back then seemed impossible but it happened," said Downes. "It would probably be even harder now. For one thing, ground regulations have changed and even if Kingsmeadow was expanded, I doubt if it could cope with Premier League standards.

"And given what the club is all about the last thing they would surely want to do is move. Also what you tend to see happen now is that as a soon as team starts to rise up the league their best players are snapped up before they can evolve into a force. But, you can't underestimate the force a sense of purpose among players and fans can bring. In a game where money counts for so much AFC have shown you can still live a dream."

What they have, chief executive Erik Samuelson, argued, is a bond. He explained: "When people come here they comment that everyone in the crowd seems to know each other. There's an extraordinary amount of socialising between our fans; we've got something special."

They are on a journey, one they hope will take them from pavement to the penthouse of the Premier League, though their immediate plans are concentrated on elevation to the band of 92 clubs in the first four tiers.

"Promotion is this season's aim," Samuelson said. "We've got a very good young team and we're doing our utmost to reach League Two. Beyond that? Who knows? We have already done what many thought impossible. But we also have to be realistic. A month's pay for a Premier League player would cover our entire season's wage bill."

AFC Wimbledon do boast one very fine Premier League player, albeit of the 1997 vintage. Marcus Gayle's combination of physical power and a lovely left foot was a factor as Wimbledon finished eighth in the top flight and reached the semi-finals of both cup competitions 14 years ago.

Now the Jamaica international is another adding legitimacy to the project. After becoming only the second player to appear for both Wimbledon and AFC Wimbledon, the 40-year-old is the coach of the latter's reserve team. However, his importance extends beyond that. "Marcus's arrival was hugely significant," Samuelson added. "He accepted nominal wages because he wanted to come back. Marcus 'gets it'. We couldn't wish for a better ambassador."

It is a case of old Wimbledon working for new. Gayle benefits from the club's prodigious youth policy, funded by the decision to plough the profits from their 2,200 season-ticket holders and 3,500 average gates back into the club. It is in keeping with their traditions.

In the heyday of Wimbledon, the club was self-financing because it produced and developed so many players. Alumni such as Dennis Wise, Nigel Winterburn, Terry Phelan, John Scales and Warren Barton went on to sign for some of the biggest clubs in the country. Others, such as Jason Euell and Carl Cort, yielded huge profits. One more, now, is the captain and personification of MK Dons: Dean Lewington who, like his father, Ray, also played for Wimbledon. The subplot of AFC's rise is that the chasm between the new club and the club from the new town has closed.

Next year, one division could separate them. Sooner or later, the two will meet. Gayle said: "No doubt it will create a huge amount of interest but for our fans it will be a non-game. As far as most are concerned MK Dons don't exist." But they do, and without them, there wouldn't be the phenomenon that is AFC Wimbledon.

* Additional reporting by Rob Shepherd