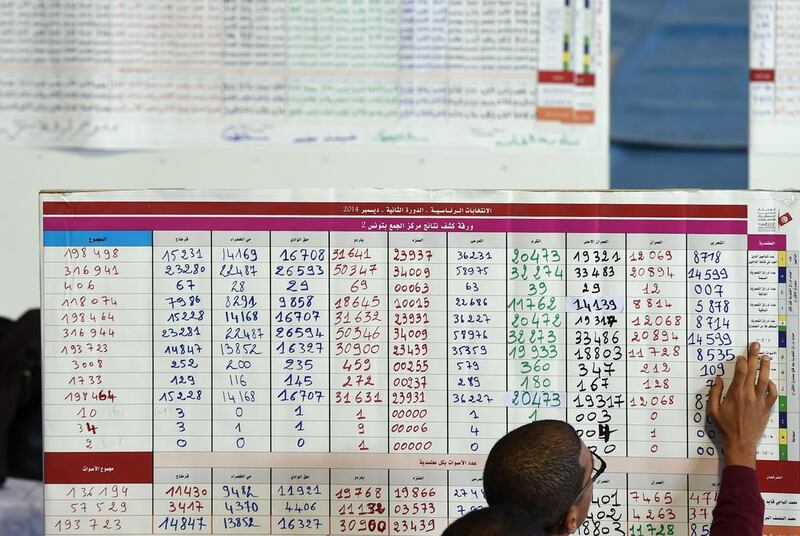

Fidel Castro, the Cuban communist revolutionary, once said: “A revolution is a struggle to the death between the future and the past.” In Tunisia’s revolution, the future and the past just collided, after Beji Caid Sebsi won the presidency in Tunisia, beating Moncef Marzouki by 10 per cent earlier this week.

There were those who compared Tunisia’s options — between a “remnant of the former regime” and the “choice of the Islamists” — to those in Egypt in 2012. In that election, voters had to choose between the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohammed Morsi, and Ahmad Shafiq, Hosni Mubarak’s last prime minister.

But Mr Marzouki is hardly the Tunisian equivalent of Mr Morsi. And while Mr Caid Sebsi is not a revolutionary figure of any repute, he was not exactly a Ben Ali stalwart either.

If there is a comparison to be made, Mr Caid Sebsi is more the equivalent of the Egyptian old guard figure, Amr Moussa — and Mr Marzouki similar to the leftist human rights activist, Khaled Ali.

In Egypt, neither did particularly well in 2012’s presidential election. In Tunisia, however, Mr Marzouki and Mr Caid Sebsi, who are far closer to the centre than one might think, faced off in the second round of voting in the presidential race.

There is much talk about polarisation in Tunisia. It is a genuine fear, and is not helped by Mr Caid Sebsi falsely claiming “Salafi jihadists” backed his opponent.

But in the aftermath of Mr Caid Sebsi’s victory, the country did not suddenly break down into violence. We might take this for granted in many democratic countries, but Tunisia does not exist in a typically democratic region. On the contrary, it stands out as an exceptional case after the last four years and the Arab uprisings.

Something else to consider in Tunisia, that has also been quite absent in other Arab countries, is its consensus-based constitution.

Would it have been better for Tunisia’s democratic experiment if Mr Marzouki had won? It would have certainly established a deeper system of checks and balances, considering Mr Caid Sebsi’s party has a plurality of seats in parliament.

If there is a counter-revolution in place in Tunisia, as a result of Mr Caid Sebsi’s victory, it has to now deal with a strong, minority party of Islamists in parliament — and a constitution that was designed to avoid the abuses of power under Ben Ali. In other words, that counter-revolution would have its work cut out for it.

Mr Caid Sebsi’s electoral victory is not the end of Tunisia’s democratic experiment — rather, it is a different stage in it. Even if Mr Marzouki had won, it is likely that at some point, a member of the former political dispensation would be president.

In fact, his election may be a very good thing for Tunisia’s democratic experiment.

Tunisia has changed and how the old guard engages with the new political landscape will be instructive. The political realities of the new Tunisia may mean that the old guard will have to moderate itself — and Mr Caid Sebsi has to deliver.

One could easily construct reasons to be wary of a Sebsi presidency. But the reality is this: Tunisia has gone through a remarkable transitional period and December 2014 marks the end of that period.

It also marks the beginning of a new phase, where everyone is locked into respecting a deeply significant constitutional document.

The region and the world should not look upon Mr Caid Sebsi as though he has a blank cheque with which to rule. He does not. In office he will be constantly reminded of his responsibilities and commitments under the Tunisian constitution and international law. The same would have applied to Mr Marzouki if he had come to power.

Caution must be the name of the game as Tunisia’s new republic matures – and one hopes it will continue to teach the Arab world lessons that resonate far beyond its borders.

Dr HA Hellyer is an associate fellow of the Royal United Services Institute in London, and the Centre for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC

On Twitter: @hahellyer