The cinemas are awash with spandex. This will hardly come as news for any moviegoer heading to the multiplex, especially over the summer. Since Bryan Singer’s X-Men landed back in 2000, Hollywood has taken the superhero movie seriously. Achieving runaway success at the box office, it has, effectively, become this generation’s western – the populist, go-to genre for mass market entertainment. As Stephen McFeely, co-writer of the recent Captain America: Civil War, stated: “It’s taking over that same black hat, white hat mythmaking surface.”

In many ways McFeely is underselling the genre; it’s more than just good-versus-evil with clear battle-lines drawn. Like the Marvel and DC comic books before them, the modern-day superhero movie is holding up a mirror to today’s increasingly complex morally-grey political climate.

Reflecting back is a very murky landscape indeed. Both Captain America: Civil War and this year’s other massive superhero release, Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice, with its superheroes operating outside the law, deal with the toxic lure of fascism, civil insurrection, and questions hanging over democracy and the establishment. These are more than just plot devices. It’s hard not to see them as reflecting a broader political conversation that needs to take place, but isn’t.

Take Captain America: Civil War, which raises a number of serious topics, questioning what (if any) is a legitimate use of force and investigating the very integrity of government institutions.

In the film, the Avengers find their unregulated heroics subject to state-sanctioned control, a move that causes deep rifts in the group. Front and centre, in this ideological tussle, is the individualism of Chris Evans’s Captain America against the authoritarian stance taken by Robert Downey Jr’s Iron Man.

Like the previous Captain America movies, aggressive US foreign policy has served as inspiration as it asks whether one country has the right to intervene in global matters.

In Civil War, when the Avengers stage a mission in Nigeria to prevent a biological weapon being fired, the resulting carnage raises points that could just as easily be debated in the UN. Namely, who should be responsible in the case of civilian collateral damage when an attempt is being made to save more lives?

These are important questions for countries around the world, but especially the United States. While the US media largely overlooks these issues, it’s left to movies to prompt such discussions.

Earlier Marvel movies have also questioned state authority. In Iron Man 2, Robert Downey Jr’s billionaire entrepreneur Tony Stark faces off with the devious Senator Stern regarding the development of his highly-sophisticated Iron Man weaponry suit. Rather than hand it over to the government, he refuses – a pointed indication that the state is not be trusted. That Stern later turns out to be an agent of evil organisation Hydra proves his point.

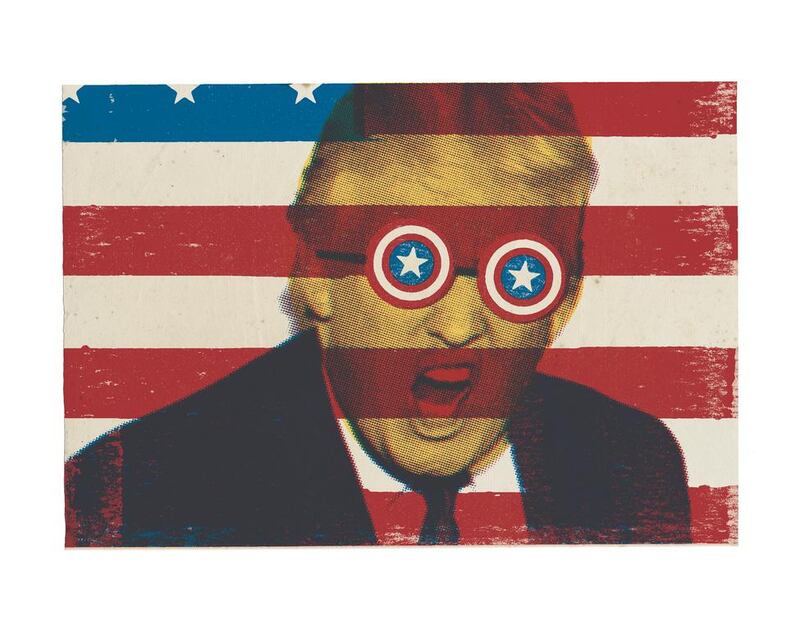

You only have to tune in to the current US electoral cycle to realise how prescient these films feel. If DC’s Batman is a vigilante delivering his own brutal form of justice in Gotham City, there’s a worrying similarity to the words of US presidential hopeful Donald Trump. The Republican candidate’s campaign rhetoric is shaded in the language of taking arms – even encouraging his supporters to “knock the crap” out of any anti-Trump protesters, as he did in Iowa earlier this year.

The comparisons go further. Like Batman’s alter-ego, Bruce Wayne, Trump is a billionaire mogul and they both have buildings emblazoned with their family name (Wayne Tower/Trump Tower). But it’s more than just the superficial. In the case of Ben Affleck’s Dark Knight in Batman vs Superman, he campaigns against the Man of Steel’s presence as an outsider, an alien – a sentiment Trump has echoed in his fearmongering about Muslims.

Trump’s rising popularity styles him as a figure outside the political establishment, like the Dark Knight, who can deliver justice. But while Batman still believes in the integrity of the courts to uphold the law, Trump seems to have contempt for the current US justice system. Quite apart from its racist overtones, his recent statement that Judge Gonzalo Curiel’s Mexican heritage represented an “absolute conflict” of interest in two class-action fraud cases against Trump University shows an utter disrespect for the rule of law.

Back in the age of New Hollywood, in the 1970s, such hot-button issues were regularly found in real-world dramas.

Films like Alan J Pakula’s The Parallax View, All The President’s Men and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation dealt with state surveillance, paranoia, assassination and White House wrongdoings. But if these topics are just as pertinent in the post-September 11 war on terror era, Hollywood’s reluctance to make political dramas has seen filmmakers turn to the superhero genre to put forth ideas.

For years, superhero comics reflected sociopolitical turmoil. Created during the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Marvel’s Black Panther frequently tackled social justice issues; likewise, DC’s Green Lantern and Green Arrow explored everything from pollution to prejudice against Native Americans. And so, with no other canvas to open up political debate on film, is it any wonder filmmakers embraced – and politicised – the genre?

Look at Christopher Nolan’s Batman films. While he strenuously denied The Dark Knight Rises (2012) – the third chapter in his Batman trilogy – was political, many read it as a right-wing critique of the Occupy Wall Street movement, when the villain Bane invades the Gotham Stock Exchange. If this indeed seems a rather narrow-minded reading, there’s no question Nolan has framed the film, and predecessors, in political terms.

Nolan’s representation of gloomy Gotham is a city overflowing with corruption and economic despair. Meditating on the state’s ability to abuse power, as he did in The Dark Knight (2008), his conclusion is quite simply that the best government is the one that respects its citizens; that liberal democracy is to be preferred to outright revolution. If nemesis The Joker is the self-proclaimed “agent of chaos”, Batman battles him to restore order to the democratic structures. Trump – take note.

Forthcoming, Zack Snyder’s Justice League (an Avengers-like superhero ensemble) and David Ayer’s Suicide Squad (the villainous equivalent) suggest a continued journey into the darker realms of the superhero story. No longer are these the strait-laced heroes of yesteryear upholding the American way; now they’re questioning it, probing it, tearing at it.

Yet should we be worried when fictional characters are used in place of genuine political discussion and debate?

Too often, the contemporary superhero movie mistrusts the government and champions the lone hero, playing into the views of Americans as a rugged, individualistic nation – the era of George W Bush. Values like compassion, social justice and equality don’t play well on the big screen.

It sets a dangerous precedent. The failure of politicians today has left us yearning for fantasy heroes to uphold our belief systems and maintain the status quo. Perhaps it’s time to retire the spandex and return to the real world.

James Mottram is a film journalist and the author, most recently, of The Sundance Kids

On Twitter: @jamesmottram