Next week, Britain votes in an election that seems likely to deliver another inconclusive result, resulting in another coalition, but with a near-cataclysmic sea-change in voting patterns in Scotland, where the Scottish National Party is heading for a remarkable triumph.

In contrast to all but two of the elections since 1966, I am not taking part. On a brief visit to the UK this month, I noticed a few posters supporting particular candidates but otherwise I have had no direct engagement. I have, therefore, been obliged to follow what’s happening through the media.

One aspect of the election has struck me: virtually no attention has been paid to foreign policy issues. That’s quite a contrast to 2005 and 2010, when Britain’s involvement in Iraq was a major issue in both elections.

Instead, campaigning, as reflected in the media, has been incredibly parochial. Immigration has been an issue and, to a lesser extent, whether or not the United Kingdom should remain a member of the European Union.

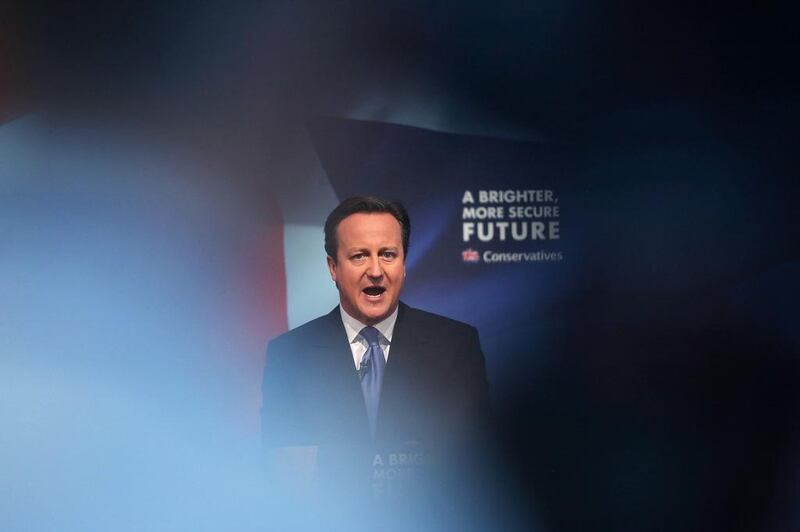

Following the drowning of hundreds of people in the Mediterranean last week, Labour’s Ed Miliband accused David Cameron, Conservative leader and prime minister, of somehow being responsible for the breakdown of governance in Libya and, therefore, for the drownings, though there is but a tenuous link between the two.

Beyond that, one or two commentators have tried to raise the issue of defence expenditure, but there has been little sign of anything else outside narrow domestic concerns.

I can understand this to some extent – bread-and-butter issues like jobs, housing and health services generally attract more attention at election time.

But it worries me that some of the major foreign policy issues of the day aren’t receiving attention in a country that is not only a permanent member of the UN Security Council and has a long history of global involvement, but also still claims to be a significant world power.

Here in the Gulf, we’re well aware of the importance of regional events. Since 2011, the region has been racked by the chaos of the Arab Spring and the humanitarian disasters that have unfolded in Syria, Iraq, Libya and elsewhere.

Iran’s nuclear ambitions and the provisional agreement reached with Tehran by the US and others, including Britain, the changes in the political and strategic geography of the Middle East, the rise of ISIL, the nightmare of the Syrian conflict, the greatest humanitarian crisis since the Second World War – all these have a relevance that stretch far beyond the region. Indeed, with hundreds of British citizens now believed to have joined ISIL, there’s a direct threat that its terrorist acts will spread back into Britain.

Closer to Britain, the Ukrainian conflict is on the edge of the European Union, while the possibility of a financial meltdown in Greece threatens economic recovery. Yet of these events and threats, the British electorate are hearing little from those vying to be part of the next UK government.

There may be few votes for any party, in government or outside, that seeks to draw the attention of Britain’s voters to the fact that warfare and humanitarian crises are stalking the globe. The sacrifices made by British soldiers in the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan have received scarcely any acknowledgement. What, though, are Britain’s partners, like the UAE, supposed to think, when British political parties, of whatever shade, appear to feel that their country’s role in world affairs is something of utter irrelevance to the electorate whose support they seek?

Looking ahead, tough choices on foreign policy issues will need to be made by any future British government. Discussion of those issues now, at election time, would, surely, contribute to better-informed decision-making in the years ahead.

Peter Hellyer is a consultant specialising in the UAE’s history and culture