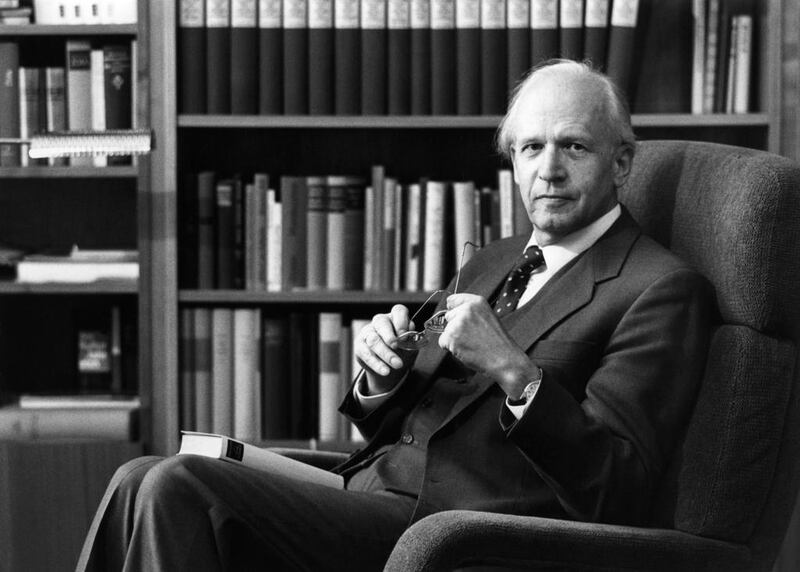

A highly controversial historian died last week. His obituary may not have been front page news, or much remarked upon outside of academic circles, but Ernst Nolte’s infamy is worth re-examining. What changed his career from that of a highly respected chronicler and analyst of fascism to being labelled an apologist for Hitler was his equation of the evils of the Nazis to those perpetrated by Communist Russia under Stalin.

Unfortunately, Nolte went further, which is probably what damned him irretrievably in the eyes of most of his peers and successors.

The first contention, however, deserves rethinking. For this designation of Nazism as being uniquely depraved, even compared to the deaths of tens of millions caused by Stalin, has far-reaching consequences.

The history of Ukrainian nationalism, for instance, is linked to the Second World War exploits of Stepan Bandera, who fought against Soviet oppression but was also allied at various points with the Nazis. (This helped the Russian attempt to label all Ukrainians involved in the Maidan revolution fascists.)

And yet, at the time Ukrainians longing for their own independence had no other realistic choice. Under the yoke of the totalitarian communist regime, the only ally willing to encourage dreams that they might one day throw it off was the other force that hemmed them in from the West: Nazi Germany. Against those two, any efforts to fight for a liberal, independent future were doomed to failure.

Western observers tend to claim that it was obvious which side those caught in a similar pincer ought to have chosen. But then they equally often come from victor countries that never had to suffer the depredations at home of either Nazism or communism. How can they tell which would have seemed the lesser evil if they had to face such an unpalatable dilemma?

Many countries had independence heroes who sided with the Axis powers, not out of shared ideology, but because it wasn’t clear cut to them why they should support their colonial masters over those who promised them liberation. Both Sukarno in Indonesia and Aung San in Myanmar were with the Japanese (although Aung San switched sides near the end when he could scent which way the wind was blowing). Neither of them are labelled collaborators today.

But Marshall Petain and General Weygand, who feared Communism more than Nazism, and led a much shrunken France to accept vassal status as the Vichy State to pre-empt “Polonisation” – the treatment meted out to Poland by the Germans – are irreparably tainted.

“If I could not be your sword, I tried to be your shield,” was Petain’s explanation after the war. But a newly liberated France, which was busy creating the myth of a resistance that very few joined, found him guilty of treason and sentenced him to death (commuted to life imprisonment due to his age and distinguished service in the First World War). Generations born since have been encouraged to dismiss him as an authoritarian collaborator.

He certainly was a reactionary. But even to attempt to understand his position is regarded as controversial. One wonders: would everyone in America or Britain believe in fighting to the end if their countries had been invaded and their armies defeated, and if continued defiance spelt the levelling of Washington and London? In that situation, whether the attacking forces were Nazi, communist or fanatics of another variety would not be beside the question, but survival could appear to many to be the more pressing consideration.

It should also be remembered that the victory the Allies won with the considerable help of Soviet Russia came at a very steep cost to the countries of eastern Europe, which endured 45 years of communist dictatorship as a result.

The Allies chose one tyrant over another, with severe consequences for hundreds of millions. They may not have been wrong to do so, but suggesting that Stalin was not as bad as Hitler – which is the assumption underlying the refusal to equate Nazism to Soviet communism – is an insult to all those who suffered the horrors of the Georgian’s capricious rule.

Stalin has, perhaps, benefited from the tendency among leftists and liberals to regard communism indulgently. Many of Europe’s democracies had strong communist parties until relatively recently. Its adherents may be wrong, is the attitude, but at least their hearts are in the right place. Isn’t everyone in favour of liberating the masses from the oppression of despotic elites?

Quite apart from the fact that it is hard to think of any communist-ruled country in which an array of civil liberties have not been dispensed with, dissidents jailed and many of its citizens impoverished or starved to death, it must be abundantly clear that there was nothing remotely benign about Stalin.

No one in their right mind would ever have freely chosen to submit to the authority of his murderous regime – unless the alternative was even worse. And in the context of the late 1930s, at which point Stalin’s victims vastly outnumbered Hitler’s, why should Nazism have seemed so much worse than Soviet communism?

History may be black and white certainty to those who never had to submit to one of those two evils. But much of the rest of the world knows that it is grey, and will remain so unless we wish to insult countries such as Indonesia and Myanmar by rebranding their independence heroes treasonous collaborators.

Nolte didn’t deserve to be condemned for acknowledging that, and armchair judges should refrain from issuing their verdicts on those who made the “wrong” choice. Given the alternatives of Stalin and Hitler – or even your former colonial master – how could there be a “right” one?

Sholto Byrnes is a senior fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia