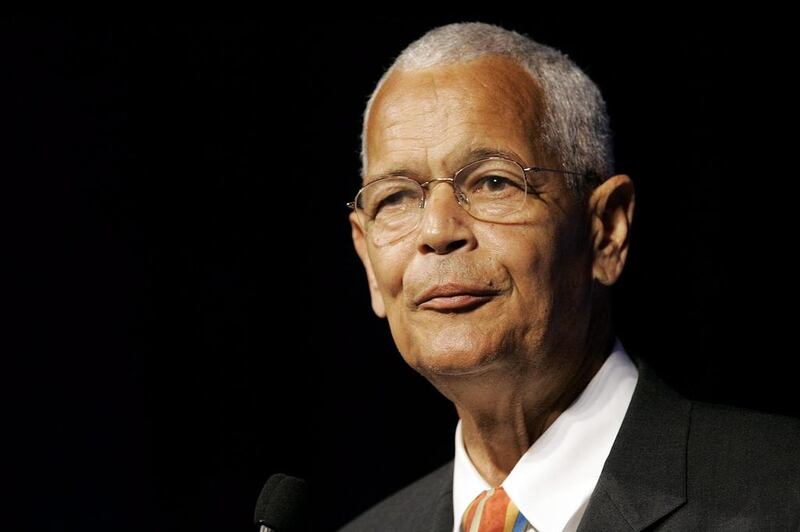

When Julian Bond died last week, every major news outlet in the United States featured tributes praising his more than five decades of leadership in the struggle for civil rights. He was all the things that were said about him. He was courageous and visionary, a steady hand and a thoughtful strategist, and a tireless and eloquent voice for justice for all who were denied their rights.

But for me, he was more. He was a mentor who more than four decades ago taught me a lesson that has guided my work.

The story begins at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. In the preceding months, the US had been shaken by a series of traumatic developments. Martin Luther King Jr had been assassinated in April. Three popular anti-war senators – Eugene McCarthy, Robert Kennedy and George McGovern – were running strong campaigns against president Lyndon Johnson, opposing his Vietnam War policy. Their combined successes ultimately forced Johnson to announce that he would withdraw from the contest. And then, in early June, Kennedy was assassinated.

When Democrats gathered in Chicago in August, they were still reeling from the shock.

Outside, there were massive demonstrations against the war in Vietnam coupled with substantial gatherings of “counterculture” activists. At one point, the demonstrations were confronted by a shameful display of police/military force. There were tanks in the streets, beatings and tear-gassing of protesters who chanted “the whole world is watching” because what was playing out in the streets of Chicago was reminiscent of scenes of uprising and repression in the USSR.

As the convention proceedings began, there was a battle over which delegation should receive credentials to represent the state of Georgia – an all-white group or a mixed-race delegation that included Julian Bond. There was some drama, but the integrated slate won.

Then came a platform fight over a plank to oppose the war in Vietnam. The anti-war plank was defeated, but in a last-ditch effort to continue their protest, party progressives decided to contest the party regulars’ hand-picked choice for vice-president, Senator Ed Muskie. They put Julian Bond’s name forward to run on the ticket with the party’s presidential nominee, Hubert Humphrey. Humphrey, who, as a senator had a sterling record in civil rights and labour rights, had been Johnson’s vice-president and was viewed with suspicion by anti-war Democrats.

The party regulars who supported Muskie were too strong and won the day. Outraged by the way their concerns had been ignored and by the use of force against the demonstrators, the anti-war delegates stood on the floor of the convention chanting the name of their candidate: “Julian Bond”. The convention’s leadership brought in police to bring order.

On the final day of the convention, after Humphrey and Muskie had delivered their acceptance speeches and stood centre-stage amid the balloons and confetti, a remarkable thing occurred. On to the stage walked Julian Bond. He went over to Humphrey and Muskie and joined hands. Like many other activists at the time, I was bewildered and devastated.

A few years later, I met Bond. He had come to lecture at a college where I was teaching. I asked him why he walked out on to the stage that night and told him how let down I had felt.

He told me that there were two types of people. There were those who looked at the evils of this world like war, racism and oppression and said: “I’m going to stand on my principles because it’s got to get a lot worse before it gets any better.” Then there were those who would say: “I’ve got to get to work to see if I can make it at least better.”

“I’m with the second group,” he said, “because if I took the first view I would be allowing too many people to continue to suffer while I, maintaining my ideological purity, refused to do anything to help them. At that point in the convention, it was no longer Julian Bond versus Ed Muskie. It was Hubert Humphrey versus Richard Nixon and I had to make a choice as to who would help make life at least a little bit better.”

I never forgot that lesson and am challenged daily to apply it. It is the reason I have so little patience for ideologues from the right or the left. They wear their purity with great pride. They arrogantly dismiss those with whom they disagree and never see the need to engage differing opinions. Because they see themselves as bearers of the only truth, they are quick to denounce others, as they say, “with clarity and conviction”.

They often miss the muck of the reality in which most of us live and the tough, less-than-perfect choices with which we are confronted in the challenge to make life a little better for those who are most vulnerable.

So, at his passing, I am compelled to say: “For the life you lived, the leadership you demonstrated, the victories you won, and especially for the lessons you taught, thank you Julian Bond.”

James Zogby is the president of the Arab American Institute

On Twitter: @aaiusa