Describing the Indian parliament as the “sanctum sanctorum of democracy” and urging all members of parliament to work in a “spirit of cooperation and mutual accommodation”, president Pranab Mukherjee opened the budget session last week.

This is an important moment for the government of Narendra Modi. It wants to pass six ordinances, including an increase in the foreign direct investment in insurance from 26 per cent to 49 per cent, and changes to the land acquisition bill. Opposition parties have united to oppose that particular piece of legislation, stating that the bill will force the poor to lose their land.

Anticipation was high that the government would announce sweeping economic reforms. In its first budget presented in July 2014, it focused on infrastructure development, streamlining of subsidies and easing restrictions on foreign investment. Though it was seen as lacking in ambition, that budget was widely welcomed.

The Modi government has also initiated an overhaul of creaky labour rules, cutting the power of labour inspectors and slashing red tape for small companies. It has agreed to allow private Indian companies to mine and sell coal, setting the stage for the biggest liberalisation of the industry in more than 40 years.

Defying his own party’s old guard with their belief in swadeshi – or self-sufficiency and distrust of foreign companies – the Modi government has been calling for major powers to enter the full range of Indian industries and rolling out the red carpet for the global corporate sector with his “Make in India” campaign.

At the same time, Mr Modi has also been keen to reach out to the public with his plan to build toilets and a programme to help Indians open bank accounts.

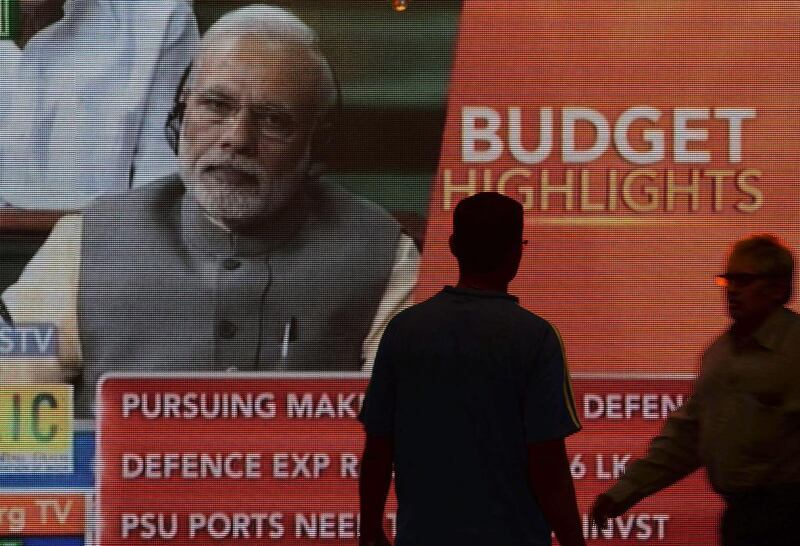

The focus of this budget is on boosting growth, infrastructure, and investment in the economy. Finance minister Arun Jaitley introduced plans for a universal social security scheme and proposed significant benefits for the poor.

Other major announcements included replacing the wealth tax with an additional surcharge on taxpayers earning higher incomes, building five “ultra mega” power projects of 4,000 megawatts, and infrastructure spending of $11.3 billion (Dh41.5bn).

During his speech Mr Jaitley said: “We have turned around the economy, dramatically restoring macroeconomic stability and are creating the conditions for sustainable poverty elimination, job creation, durable double digit economic growth.”

Talking about infrastructure, Mr Jaitley said: “It is no secret that the major slippage in the last decade has been on the infrastructure front. Our infrastructure does not match our growth ambitions. There is a pressing need to increase public investment.”

In response to the budget, P Chidambaram, India’s former finance minister said: “One cannot avoid the feeling that the budget leans heavily in favour of the corporate sector and the class that pays income tax ... What is the government’s leaning? Does it lean towards the poor? The answer appears to be no. It says when growth happens you will get the benefit, but until then fend for yourself.”

While debate on the budget will continue, it’s the politics of the budget that is crucial for the Modi government.

Politics is about perceptions. Despite a number of important initiatives from the Modi government, a feeling has gained ground that there is no broader vision behind government policies, that everything is random.

Without establishing why the Modi government is radically different from its predecessors, it may have to rely on tactical gimmicks to stay afloat.

Mr Modi needs a frame to organise his responses to the myriad problems confronting the nation. In most successful political careers, there is a purpose, a guiding philosophy which is the foundation, all the rest is secondary. Separate and seemingly unconnected strands do not add up to coherence.

Mr Modi needs to reaffirm at this juncture that India is an organic entity, that no interest, no class, no section is either separate or supreme.

The annual budget had offered the government an opportunity to change the narrative, to tell the Indians and the outside world that it means business.

The Modi government needs to put in place a programme of action that will allow the country to reach its full potential. It’s not clear that it has succeeded in dramatically altering the perception about its policies with this budget. The economics of the new budget are certainly sound. But the politics leaves much to be desired.

Harsh V Pant is a professor of international relations at King’s College London