The term “Lutyens’ Delhi” refers to both an abstract and a physical location. In the abstract, it refers to the Indian capital’s circles of political power. Those circles overlap with the physical space that is Lutyens’ Delhi – the heart of the city, designed during the Raj by the British architect Edwin Lutyens.

Working between 1914 and 1931, Lutyens laid out one of the loveliest urban spaces in the country, full of parks, wide avenues and roadside trees. But when it came to naming these roads, wrote Mala Dayal in her book Celebrating Delhi, "there was a depressing lack of imagination".

The British planners reached for obvious choices, Dayal noted: old Indian emperors. Hence the presence of Prithviraj Road, named after a 12th century Rajput ruler; or Akbar, Humayun, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb roads, named after the Mughal dynasts; or Ashoka Road, after the king who ruled large swathes of India in the 3rd century BC.

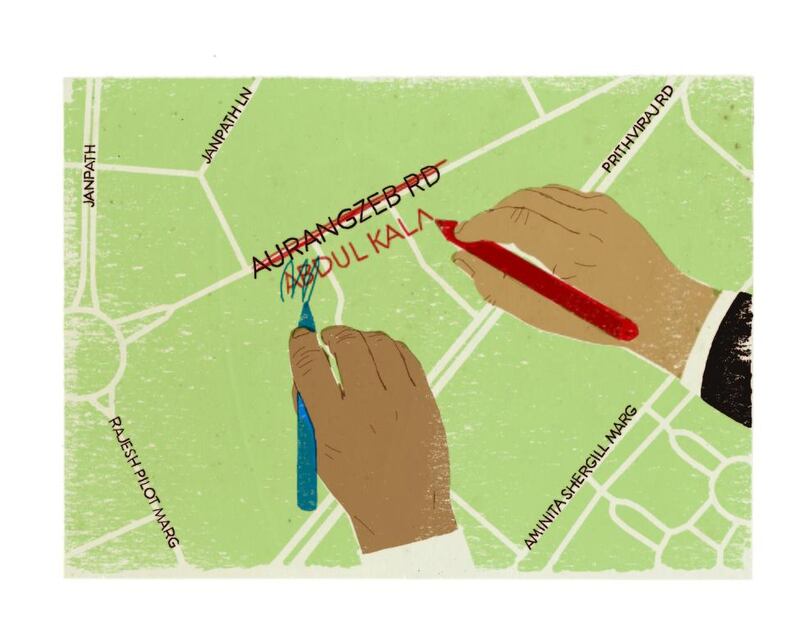

One of these avenues, Aurangzeb Road, runs not far from the prime minister’s residence. It is a short road, spanning just four intersections from end to end. But over the past few days, Aurangzeb Road has been at the heart of heated debate, after the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) announced a plan to rename it in honour of APJ Abdul Kalam, the former president of India.

Abdul Kalam, who occupied the presidency between 2002 and 2007, died on July 27. His death triggered a vast outpouring of grief and tributes, a demonstration of how popular a figure he was for his soft-spoken geniality and his unimpeachable integrity.

So a move to honour Kalam shouldn’t have generated much controversy. But the act of naming and renaming places, landmarks and roads in India is always rich with political significance, and this case is no different.

Take Aurangzeb’s place in Indian history, for starters. Ruling between 1658 and 1707, Aurangzeb proved an authoritarian and narrow-minded ruler. He had three of his brothers killed and he executed freethinkers. His reign was notable for its brutal persecution of Hindus and Sikhs.

So persistent is this horrific legacy that the word "Aurangzeb" still carries negative connotations in some Indian languages. "Don't be an Aurangzeb," an elderly lady scolds a young man in the recent Mani Ratnam movie OK Kanmani, for the sin of failing to appreciate a classical music concert.

But it has not escaped the notice of many commentators that the renaming of Aurangzeb Road has happened during the tenure of prime minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, which has pronounced Hindu nationalist tendencies.

The chair of the NDMC, which administers the roads of Lutyens’ Delhi, is an appointee of Mr Modi’s federal government. The renaming, thus, is seen as a BJP move to erase the memory of a Muslim despot and substitute it with that of a Muslim who professed a deep love for Hindu thought and culture.

The move has invited both scathing comment and legal objection. Writing in a piece for The Wire, a digital news site, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, the former governor of West Bengal and the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, called the proposal to rename the road "puerile history and childish civic planning".

Mr Gandhi wrote that “as one who despises everything that Aurangzeb did to his family and to his populace”, he added his voice to that of those who oppose doing to Aurangzeb what Aurangzeb did to others. This was not because Aurangzeb was repugnant, but because behaving like Aurangzeb was repugnant.

“He is not in fact being executed in this act; he is being brought to life again.”

A legal petition also contends that the move violates a 1975 law banning the renaming of streets or roads that are already named after people. “The decision is totally illegal, unjustified, arbitrary and against our constitutional ethos. It appears to be guided by not reason and law, but by narrow communal consideration,” a statement by the non-profit Citizens for Democracy said.

But India has forever rejected Shakespeare's argument – "a rose by any other name would smell as sweet" – that names are immaterial.

Here, the nomenclature of public spaces – cities, roads, railway services, bridges and buildings – is a popular, if immature, way to assert political authority.

The Nehru-Gandhi family, which controls the Congress party, has been particularly fond of this method. India’s cities are littered with infrastructure and buildings named after that family’s members: by one count, at least six ports and airports, 15 wildlife parks, 39 hospitals and 47 sports tournaments and stadiums.

Administrations also appear to believe that by renaming an object, they can rub away the decades or centuries of regrettable history signified by the original name. This is why, for instance, Victoria Terminus in Mumbai was renamed Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, substituting the British imperial ruler for a local Maratha one. It is also why Mumbai itself left its old name of Bombay behind, as Chennai did with Madras and Kolkata with Calcutta. The history of the Raj still rankled enough to want to shed these old colonial names.

I’m from Chennai, and I still can’t bring myself to call it that, even though the city changed its name in 1996. To me, the change seemed silly. The name Madras had been in use for at least 250 years, if not more, and it had woven itself into the texture of the city. The name Chennai is not even significantly older than Madras – merely 100 years, a thin slice of the city’s millennia-long history.

The mania for renaming places must, in India’s own interests, stop soon.

Aurangzeb may be an egregious example – a tyrant who deserves no celebration. But where does this trend stop? There are always slights of history that some people will wish to rectify or erase, and there can always be a group of people that can claim a grievance against any historical person. To acquiesce to all of these demands would lead to chaos.

Indeed, a truly sound rejection of Aurangzeb and his legacy would be to conduct the nation’s affairs in a manner opposite to his own – to leave aside authoritarian tendencies, and to attempt to knit the country’s various faiths and creeds together so that no community feels fearful.

But the Hindu nationalists, who pitched so strongly for the trivial renaming of a single road, don’t seem prepared to walk down the more difficult path as yet.

Samanth Subramanian is a foreign correspondent in New Delhi