By the 1950s, Britain’s decades-long colonial project in Kenya was crumbling. The country struggled to maintain its control and as the Mau Mau uprising spread and strengthened, the British resorted to brutal, illegal tactics. Forced labour, torture and extra-judicial killing were used to pacify the population.

Half a century later, what happened in the years before 1960 in East Africa is still a matter of fierce debate. Last year, after years fighting the matter in the courts, the British government conceded that it had used torture, apologised and offered token compensation to 5,200 Kenyans.

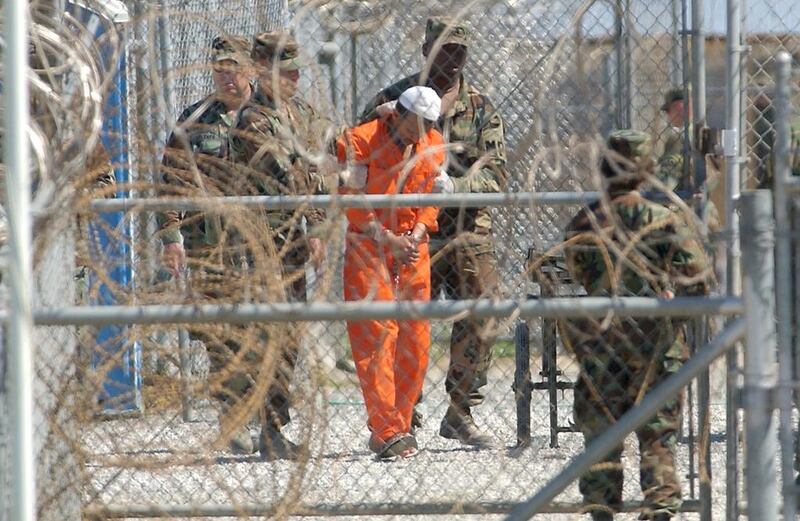

A lifetime later and half a world away, the same questions are being raised over Guantanamo Bay.

The circumstances that led Kenyans to be imprisoned in illegal camps by the British in the 1950s and America after 9/11 to incarcerate without trial hundreds of citizens from around the world – including children – are very different, but what they have in common is an extraordinary and legally unprecedented response to a new military situation.

The repercussions of both will also be felt for decades, long after the architects of the policy have left political office.

The problem of Guantanamo Bay has never been about the people who are incarcerated – many of them are certainly dangerous and would probably be convicted by a court of law – but about the way they are treated.

Keeping people in legal limbo for years on end is often framed as a moral failing – Mr Obama has spoken of how the prison is against “American values” – but in fact it is a failure of the rule of law.

Most politicians – and indeed people – living in safe, rich countries have very little experience or understanding of what a society without the rule of law is like.

It is not simply about danger. The rule of law is the foundation of any society. It is not an exaggeration to say that without it, even without the appearance of it, a society corrupts and crumbles from the inside.

The American public may have largely forgotten about Guantanamo Bay, but the rest of the world has not.

The “excess nexus” of actions beyond the legal system that occurred after 9/11 – black sites, torture, extraordinary rendition – all weakened the rule of law, both in the US and abroad.

The architects of these policies took rash decisions, but those decisions spiralled into a mass unravelling of established legality. What seemed like political expediency in the moment was actually an attack on the fabric of civilisation.

If that seems like an overwrought sentiment, consider that the rule of law is an edifice that can take years, decades, even centuries to construct – but can be pulled down in an instant. Once it has, it changes and rearranges the whole society around it.

Barack Obama is desperately trying to close Guantanamo before he leaves office in 2016. Regardless of whether the physical facility is closed, the idea of – and the repercussions of – the prison will linger.

Firstly because there will be endless legal challenges: inquiries, litigation, claims of compensation. Whether they come in the next few years or the next few decades they will, surely, come.

Secondly, what happened in Guantanamo has provided anti-US groups with powerful symbols of propaganda. Stretching back to Iraq, when American and western hostages are paraded in front of cameras, they are usually dressed in orange jumpsuits, referencing the type prisoners in Guantanamo wear. Both US citizens killed in recent months by ISIL were executed wearing orange jumpsuits.

Thirdly, the dilution of the rule of law – on a global scale like the invasion of Iraq and on a smaller scale like detention without trial or extra-judicial deaths from drones – continues to be felt. Russia’s annexation of Crimea and China’s unilateral decision to enforce an air defence identification zone over disputed islands are both examples of big countries, in a post-Iraq global order, feeling they can act by force simply because of their power. The past decade has set back the cause of a global rules-based order.

Mr Obama is the 44th president of the US. The Mau Mau rebellion was put down before he was born, although he has written about how his grandfather was imprisoned and tortured by the British. Don’t be surprised if a future US president, not yet even born, is still wrestling with the repercussions of Guantanamo Bay half a century from now. Some mistakes take many decades to be fixed and many more to be forgotten.

falyafai@thenational.ae

On Twitter: @FaisalAlYafai