When the dust settles from the latest round of violence in Gaza, there is unlikely to be any discernible change in the delicate relationship between Israel and the Palestinians. What has changed, however, are the regional alliances that form the backbone of support for Israel’s occupation of Palestinian life and land.

The Gaza operation fits neatly with an increasingly openly-stated Israeli view that the conflict with the Palestinians can only be managed, not resolved via the creation of an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel.

Over the past 20 years, Israel has severed the West Bank from the Gaza Strip through border closures, the drying up of visas and a crippling economic siege on the Strip. The goal was to ensure Palestinian disunity and, thus, hobble unified Palestinian resistance to Israeli control.

Just before the outbreak of this war, Hamas had agreed to an important reconciliation agreement with the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, which would have seen the territories unite and set the stage for a single Palestinian entity. After 27 days of fighting, the possibility for Palestinian reconciliation looks faint.

For Israel, this war entrenched the status quo and thus allows for continued Israeli occupation. But for the international community, a new set of regional alliances has solidified over the last month of fighting. With their support for the Muslim Brotherhood, Turkey and Qatar stand in strong opposition to an Egyptian-led alliance of other Gulf states and Jordan that view the Muslim Brotherhood as a destabilising force in the region.

These alliances have slowly metastasised after the region’s political uprisings. At the centre of this political realignment is Turkey, which will hold its first direct presidential election tomorrow.

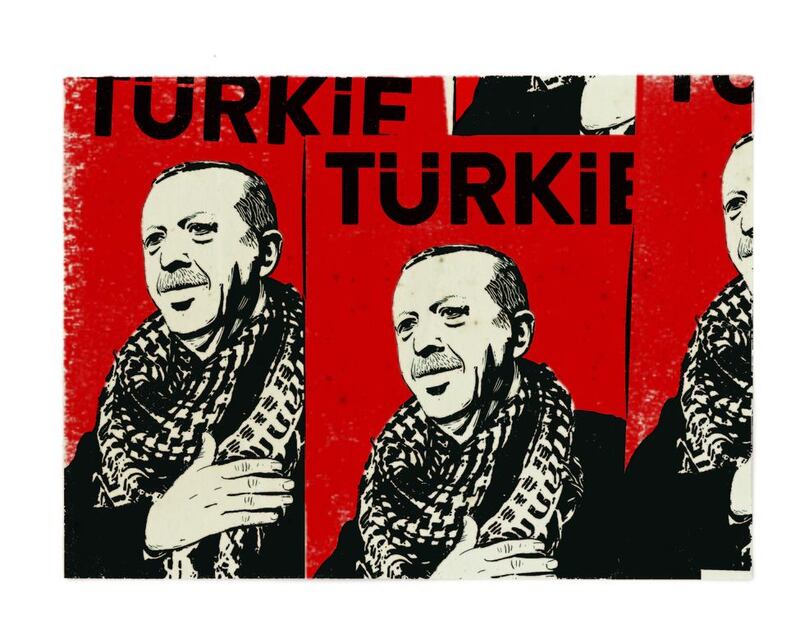

A few years ago, Turkey was the emerging superpower in the region. Under the leadership of prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey's economy was booming, while its foreign ministry was aggressively asserting a "zero problems with neighbours" strategy.

When Mr Erdogan visited Cairo after the election of Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi, the policy was evident in the hero’s welcome the prime minister received.

But what a difference two years can make. In the aftermath of the change of government in Egypt and the chaos in Gaza, Turkey is facing nothing but problems in the region.

From Syria to Egypt, the developments in the Middle East aren’t moving in a direction that Mr Erdogan would like, and Turkey is running the risk of isolating traditional allies as it reconciles its schizophrenic foreign policy.

The deteriorating situation in Syria and Iraq represent the greatest foreign policy challenge for Mr Erdogan. By turning a blind eye to thousands of foreign jihadi fighters using Turkey as a land bridge into Syria early in the Syrian civil war, Turkey now faces the possibility of blowback if the border policies are changed in a dramatic way.

Many towns in southern Turkey such as Gaziantep and Hatay are essentially bases for myriad actors fighting in the Syrian civil war.

Just last week, thousands of Islamic State supporters held a massive rally an hour outside the southern Turkish city of Mardin in a display of Turkey’s jihadi predicament.

To divert attention from this crisis at home and on Turkey’s borders, Mr Erdogan has ratcheted up rhetoric about Palestine even though his position as a serious broker in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is questionable. Ankara’s attempt to involve itself in resolving the current round of violence in Gaza has engendered anger from a variety of players, not just Israel. Both the Palestinian Authority and Egypt expressed concern about Turkey’s position as a mediator because of the country’s explicit support for Hamas.

It is not hard to see why. Recently, Foreign Minister Ahmed Davutoglu said: “We support Hamas because we defend the Palestinian cause. Hamas doesn’t have an authoritarian leadership and has divergent opinions in its ranks.”

With Turkey’s economy in a slump and a continuing corruption probe that has revealed endemic graft in his party, Mr Erdogan has deftly used the Gaza crisis as a campaign tool, casting himself as one of the only leaders in the region to champion Palestinian rights.

Officially, Turkey and Israel are still at odds over the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident, in which nine Turkish civilians were killed by Israeli commandos while attempting to break the naval siege of the Gaza Strip. However, economically the countries have never been closer, with 2014 set to become the biggest year yet of bilateral trade between them.

In the realm of aviation, for example, Israelis are continuing to use Istanbul as their main gateway to the world. Turkish carriers are even moving to expand in Israel. Low-cost Turkish carrier Atlasjet announced, at the height of the Gaza crisis, that it was going to open a new route linking Tel Aviv to Istanbul with the option of connecting to Odessa and Kiev in Russia and Ukraine.

Turkey’s increasingly inflammatory rhetoric about Israel runs the risk of damaging US-Turkish relations at a pivotal time for the region. In a recent letter, senior members of the US Congress strongly advised Mr Erdogan to tone down what they claimed was his borderline anti-Semitic rhetoric about Israel. They warned that he was running the risk of damaging already bruised ties between the US and Turkey.

Where does all of this leave Turkey’s embattled and authoritarian leader? Save for addressing the challenges facing his country, what can Mr Erdogan do to win the presidential election and become the most powerful politician in Turkish history since Mustafa Kemal Ataturk? The answer lies in the careful deployment of Palestinian solidarity.

In 2009, Mr Erdogan publicly insulted the then Israeli president Shimon Peres at the World Economic Forum in Davos. The video of his comments went viral on the internet and solidified the Turkish leader’s position in the Muslim world as a champion of Palestinian rights.

Since then, Mr Erdogan has used the Palestine issue when he needs to deflect attention from more pressing social and political issues. Over the past several months, he has carefully obscured the depth of Turkey’s economic problems and the high levels of corruption in his government through the deployment of verbose rhetoric in support of the Palestinian people.

This embrace of Palestine will ensure an Erdogan victory in Sunday’s presidential election but will not change the myriad foreign policy challenges that plague Turkey. Mr Erdogan wants to cast himself as a political leader of the Muslim world and, ironically, his abuse of the Palestine cause is helping him achieve that goal.

Joseph Dana is a regular contributor to The National

On Twitter: @ibnezra