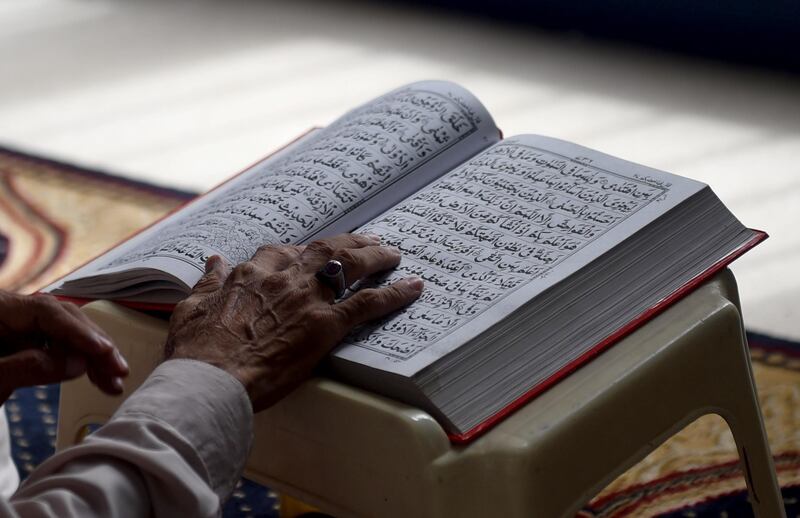

On the website of the main body responsible for printing and distributing copies of the Quran worldwide, there is a list of 45 verses that some Islamic scholars historically considered to be overturned by other verses.

Of the 45 verses, 22 were “abrogated” by one verse that Islamic extremists use to justify perpetual violence against non-Muslims.

Abrogation is a known process in Islamic jurisprudence. Scholars claim that certain verses in the Quran, which was revealed over a period of more than 20 years, were annulled by verses that came later. The process has been a point of contention among Muslim scholars throughout history. Some rejected its legitimacy, while most differed over which verses could be regarded as overturned.

The verse in question is commonly referred to as the Sword Verse, which in part translates as: "slay the idolators whenever you find them". It is the most cited verse by both extremists and critics on Islamic justifications of violence against those deemed "infidels". Mainstream clerics explain that the verse spoke of a particular event in the past, as indicated by the verses after it, which call for the Prophet to protect those who seek refuge and to then ensure they reach safety.

_____________________

Read more:

What ISIL really thinks about the future

Naming ISIL’s ideology does not help defeat it

_____________________

The purpose of the list by the King Fahd Complex - a centre specialising in the printing of the Quran, based in Madina, Saudi Arabia - is to discredit a foundational argument for violence committed in the name of Islam.

At the bottom of the list, the authors conclude that scholars historically had no consensus over abrogation except in two cases. The two cases are related to nightly prayers and the payment of alms during the time of the Prophet. In the remaining examples, scholars were divided (in Sunni Islam, consensus is one of the requirements for a view to be regarded as binding). Thus, the centre suggests that the verses widely seen as abrogated by the Sword Verse were not, in fact, abrogated.

Most of the verses said to be overturned by the Sword Verse call on Muslims to accept peace during war despite an opponent’s possible insincerity, to exercise restraint, to forgive, to abide by agreements and to avoid being provoked. One verse, for example, reads: “And if they incline to peace, incline to it and trust in God.” Another says: “Pardon and be forgiving until God brings his command.” In a third verse, the Quran says: “Turn away from them, and say ‘Peace!’ But soon shall they know.”

For extremists, all three verses – and many non-confrontational others – are vetoed by the generalised call for slaying infidels wherever they are found. And yet, the effort to highlight the minority voice of such views in Islamic history is a necessary step in the ideological fight against extremism today. Even though such efforts are, in fact, widespread, they often remain obscure. Two examples related to suicide terrorism stand out in this instance.

Sayyid Imam Al Sharif, an Egyptian author of two of the most influential jihadist books in recent decades, issued a fatwa several years ago forbidding terrorist attacks in the West on the grounds that when a Muslim is given a visit visa, residency or citizenship in a western country, such documents are regarded as a covenant of peace that Muslims cannot violate. Even in a hostile context, according to traditionalists, a salute could be considered a peace gesture that should not be breached. That such a fatwa came from a jihadist ideologue, revered by Al Qaeda and ISIL, is a significant development. But still, it received little attention.

Another example is the retraction by Youssef Al Qaradawi of his notorious fatwa in which he justified suicide attacks by Palestinians. In July last year, he quietly changed his view on the matter, but the shift was barely reported in media. “The Palestinian brothers were in need of the [tactic] to instill terror in the hearts of Israelis,” he said in a television interview. “They told me they no longer need it, so I told them I no longer approve of it.”

Al Qaradawi did not outlaw the practice outright, nor did he address a similar fatwa made in the context of the Syrian conflict. His fatwa may have already done too much damage, especially coming from a mainstream cleric. But the retraction should have received more attention to show the warped logic of such views.

When he described suicide attacks as “of the greatest forms of jihad” in April 2001, the fatwa was widely reported in Arabic media – in sharp contrast to his retraction 15 years later. The comprehensive list to discredit a critical argument used by extremists was not reported anywhere. Such examples show how easy it is for extremist views to become widespread and how difficult it is for their damage to be reversed.

Efforts to counter extremism rarely match the vigour with which radicals propagate their message. This is one of the reasons why extremists operate with ideological impunity, rarely countered with the same energy. With the unprecedented havoc caused by extremism to diverse communities in the region, it is time to make the opposing views heard loud and clear.

Hassan Hassan is a senior fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy