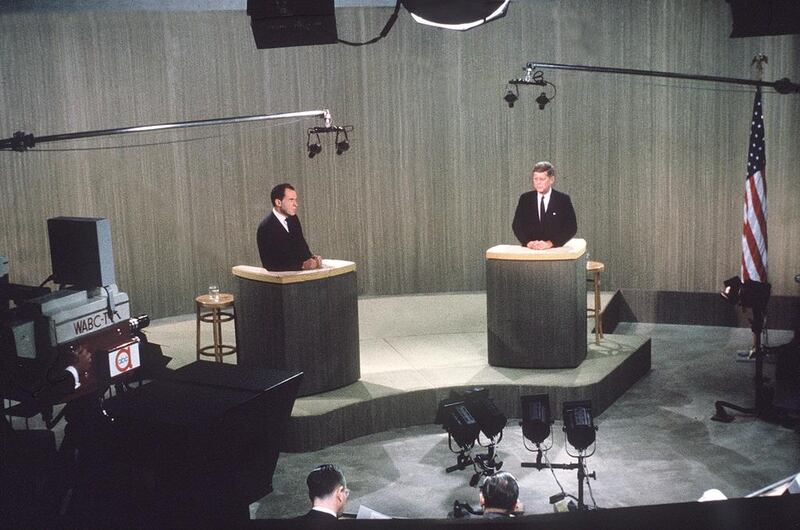

In one small and specific way US president Donald Trump is the inheritor of John F Kennedy. On September 26, 1960, then senator Kennedy took part in a national presidential debate against Richard Nixon. The outcome of the debate is legendary.

Those who had listened on the radio were clear that Nixon had won. But this was 1960, when television was suddenly ubiquitous.

Nearly 74 million people watched Kennedy and Nixon on the small screen. They far outnumbered the wireless listeners.

They felt that Kennedy had won the debate. Nixon had been ill, and appeared pale and underweight. Good looking Kennedy looked composed.

It was the magic of television that had anointed the next American president.

Fast forward nearly 60 years, and without doubt, the choreography of politics and, in particular, the sparkling seduction of television play an absolutely central role when it comes to making up our minds about political leaders.

Last week’s victory speech by Emmanuel Macron, the new president of France, was choreographed for precisely such effect.

The ceremony was held at the Louvre, a location that has connections neither with the political right nor left. The European Union anthem was carefully selected as the soundtrack. This was a spectacle for the masses.

Perhaps the least aesthetic example of the power of television in countering traditional moves of asserting power was the case of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Last year, his country faced a well-organised coup.

The perpetrators had moved swiftly on state television and traditional institutions and forms of communication.

What might be considered the turning point was itself a coup by Mr Erdogan. From a room where he was locked in with his advisers he did what the rebels had not anticipated – used the intimacy of reality television. He called by FaceTime to a private news station – CNN Turk – and asked for his face to be turned to the camera. And he spoke to Turkey.

In the full throes of the United Kingdom election campaign, incumbent prime minister Theresa May and her husband sat on the sofa to be interviewed on one of the country’s least-political programmes. The cosy couple discussed who was responsible for taking out the bins.

They giggled – no doubt at their ghostwritten off-the-cuff comments – about “girl jobs” and “boy jobs”. For the most important person of a country’s political future, what was stark was the absence of any challenge or probing on politics and policy.

You don’t need to be a cynic to know that television appearances are carefully scripted. Behind the scenes permission is only granted when the area of questioning is limited.

The television programme wants the coup of the appearance, and relinquishes the political opportunity in exchange for entertainment value. Politics as spectacle. And spectacles require choreography.

Of course, there’s always been something about the drama of politics that sweeps followers into its wake. I’m not making any analogies here with the tone or content, which is too horrific to contemplate. People often speak of the mesmerising nature of Hitler’s rallies on his way into power. There are descriptions of the vast stadiums in which he performed and how he knew how to manipulate silence, waiting with the energy of the crowd.

What is different now is that television has a certain intimacy that makes us forget the theatrics involved. And reality TV in particular is crafted so we think it is real. But it’s not real, rather it purports to be realistic. President Trump, with his string of television appearances and a well-crafted television persona, is in this regard its direct beneficiary.

It’s been said plenty of times, but as viewers we must be mindful that television is not reality, and the lines between politics and TV are remarkably fuzzy.

Instead of retaining its position as a means of political accessibility, accountability and intimacy – as it felt in the Kennedy era – television is rapidly turning politics into sheer entertainment.

We must be vigilant that television doesn’t literally become the ultimate all-pervasive embodiment of the political strategy of bread and circuses.

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed is the author of the books Generation M: Young Muslims Changing the World and Love in a Headscarf