Three months after the spark that gave rise to the uprisings of 2011, Syria changed forever. No doubt many Syrians will now wish for a reset of the situation so they could do things differently, but a reset does not necessarily mean a desire for life under the same regime, in the same way that many Iraqis hanker for the pre-war stability they enjoyed rather than a wish to live under Saddam Hussein’s rule again.

This distinction is worth bearing in mind as a new round of peace talks – including attempts to deal with rising extremism – begins by countries involved in the Syrian conflict.

Over the weekend, Syrians reflected on the beginnings of the conflict through a campaign of support for the Free Syrian Army.

Each one of the past five years was defined by a broad theme that would add to the intractability of the Syrian conflict.

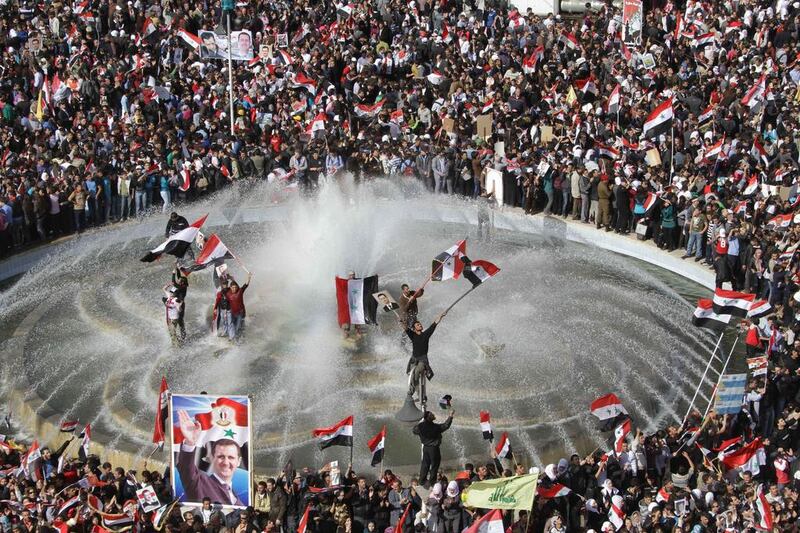

The first year was defined by the courage of men and women who revolted against the brutal rule of the Al Assad clan, courage that surprised many in the country and outside. It would even take around three months of protests for Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya, which had back-to-back coverage of the other uprisings from day one, to dedicate similar coverage for the protests to Syria.

It also took the same time for Saudi Arabia and other countries to condemn the ruthless campaign of terror against protesters and take diplomatic measures against the regime. In the years leading up to the uprising, the Assad regime entrenched itself in regional politics and started rapprochement with all the Gulf countries that would later turn against it.

The second year was defined by an unprecedented level of violence and regional involvement in the conflict. Iran entered the fray militarily through the provision of arms and advice from operatives claiming to be “pilgrims”.

Claims by the rebels that Iranians were fighting on the side of the regime were dismissed as propaganda by many till later that year.

Massacres in the countryside around Hama, Homs and Tartous surpassed even the violence that would later be exhibited by groups such as ISIL: pro-regime militias would shell a village overnight and sweep through the village in the early hours, slaughtering men, women and children.

Such massacres were taking place more than half a year before ISIL was formed.

The third year was when the country formally descended into a sectarian conflict. In the early months of 2013, sectarian reprisals in western Syria by rebel factions – led by ISIL, Jabhat Al Nusra and Ahrar Al Sham – were documented by Human Rights Watch. Sectarian rhetoric became more entrenched in the country and the region at large, with the growing involvement of Shia militias from Iraq and Lebanon.

The latter half of that year would be shaped by the rise of ISIL and the one-upmanship of sectarian and extremist rhetoric before and after the establishment of “the Islamic Front”, as polarisation, rivalry and incoherence led forces claiming to have an Islamic agenda to try to maintain their influence through sectarianism.

The international community’s failure to respond in a punitive fashion to the Assad regime’s repeated use of chemical attacks on civilians – despite it being a specific “red line” the West cited, with threats of punishment afterwards – signalled another key milestone. Massacres carried out by pro-regime forces in 2012 prompted many Syrians to give up on the outside world and drift further towards extremist groups.

In the fourth year, Syria was deeply fractured and nearly 40 per cent of the country was carved out by ISIL, changing the international view of the conflict from a local tragedy to an international menace.

Extremists have taken hold of much of the country and both Syrians and outsiders seem to have given up on the conflict itself.

Much of the discourse and the political effort would be driven by how to weaken the symptom – ISIL – rather than deal with the real issue. This way, neither the symptom nor the cause will be resolved effectively.

This year there is more of the same. Desperate attempts to fight ISIL involved desperate plans to find local partners that would prioritise combating the terror group over fighting the regime that was terrorising Syrians, destroying their homes, torturing and raping their family members, starving them or driving them out of the country.

Some parties were even suggesting the best way forward might be to work with Bashar Al Assad to save Syria from terrorism.

If in the first four years, the world lost its heart in the Syrian conflict, 2015 was the year when the world lost its mind.

Hassan Hassan is associate fellow at Chatham House’s Middle East and South Africa programme, a non-resident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy and co-author of ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror

On Twitter: @hxhassan