As the fighting has died down in western Syria – the focus of the toughest battles over the past six years – a race to control the less populous east of the country has broken out, involving the armies and militias controlled by the Syrian regime, Iran, Russia and the United States. The new stage of the war reflects the desires of different actors to control territory at a time when the battle lines are likely to harden for months, if not years.

The geography of Syria provides two almost separate war zones – the greener parts where most people live in the west are separated by miles of desert to the east towards the border with Iraq. This is largely vacant apart from the fertile Kurdish northern section and the Euphrates valley, in which lie the ISIL headquarters in the city of Raqqa and the isolated regime stronghold of Deir Ezzor, besieged by ISIL for three years.

Capturing territory in the east gives control of roads, which are vital both for regional trade and for Iran’s determination to establish secure land corridors to the Mediterranean and to the Syrian-Israeli border. It is this element which, in the eyes of the Iranians, elevates the contest for control of these largely empty wastes to a strategic necessity.

All sides are preparing for the new situation that will arise after the destruction of the ISIL “caliphate” in Raqqa and the final capture of the Iraqi city of Mosul, which has been in ISIL hands since 2014. The need to destroy ISIL is the one common theme among the outside powers, and the Americans and Russians are working hard to avoid their forces clashing as the ISIL end game looms.

As for the regime, it is moving up its soldiers and allied militias towards the Euphrates to be better placed to restore control over Raqqa when the black flags of ISIL are torn down.

The presence of the Americans is the big conundrum of the regime and its allies. The Americans are allied with the Kurds who control the northern part of the border with Iraq and who will be the spearhead of the attack on Raqqa. They have established a small base at Al Tanf, in the south, where the borders of Jordan, Syria and Iraq meet, to train militias for the assault on Raqqa. The Iranians fear that the Americans and their allied militias could join up in the middle of the border, effectively cutting off Iran’s access to Syria.

Fears of military confrontation spiked on May 16 when the US air force bombed some Syrian regime-allied militias which were approaching the de-confliction zone around Al Tanf, to warn them to keep their distance.

The sensitivity of the presence of the Americans and their western allies in this patch of desert is shown by an Iranian-inspired campaign to block Iraqi prime minister Haider Al Abadi’s plan to grant a 25-year concession to a US private security firm to secure and manage the highway that connects Baghdad to Syria and Jordan through some notorious badlands. This might be thought a much-needed economic benefit for the Sunni tribes who live along the highway, but it is seen by pro-Iranian militias as a sign that Americans are planning to block their path to Damascus.

The Israelis believe that Iran is trying to secure two routes across Syria: a northern path to Lebanon through territory controlled by the US-allied Kurds – and therefore perhaps insecure – and a southern route along the desert highway which would supply a future Iranian-allied militia base on the edge of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. The chances of these corridors liberating either Palestine or the Golan are slim indeed, but as demonstration of Iran’s entrenched position in the heart of the Middle East, they make a lot of sense.

With all these armed forces converging, the chances of a real shooting war between them must be high, especially as the Israelis also intrude into Syrian airspace at will. If you add the political ingredient of Donald Trump’s hint that he plans to isolate Iran until the fall of the mullahs’ regime if necessary, then it seems a recipe for catastrophe.

So far, however, the US and Russian militaries have succeeded in keeping out of each other’s way.

Even though the Israelis are operating “at some cross purposes to the Russians”, as an Israeli source says, serious efforts are in play to avoid a clash in the sky. For their part, the Americans are saying that their presence in Syria is solely for the purpose of eradicating ISIL. The Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is understood to have received assurances that the US alliance with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces militia is strictly tactical, for the joint purpose of liberating Raqqa.

The evidence suggests that the US generals in charge are level-headed and in no mood for any kind of prolonged military engagement. The small footprint of the Americans suggests that Iranian fears of permanent occupation are exaggerated. In any case, the Iranians are capable of swamping the area of Al Tanf with thousands of their allied militiamen which would constrain US ability to do anything, even if it did not lead to open fighting.

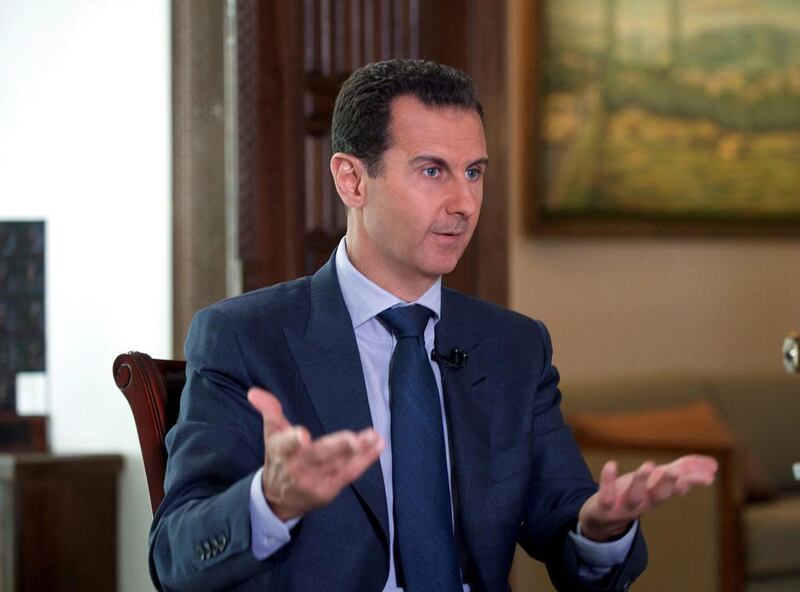

Is it really possible that the battle for Raqqa could be won and the Americans simply fold their tents and depart? This would require the liberated city of Raqqa to be handed over, after a decent interval perhaps, to the war criminals of the Syrian regime, under normal circumstances shocking and immoral conduct. But Mr Trump has made clear that he sees ISIL as a threat to the US homeland, while Bashar Al Assad is a threat only to his own people.

But what of Mr Trump’s promise to contain Iranian adventurism? That looks like a battle for another time, and one that will be fought in the trackless deserts of diplomacy rather than on the ground.

Alan Philps is a commentator on global affairs

On Twitter @aphilps