What do the Israeli election results have to do with China’s sudden stated official interest in reincarnation and the afterlife? Not much except that both reveal the two countries’ complex attitude to the place of religion in politics.

Benjamin Netanyahu is set for a historic fourth term, which would make him Israel’s longest serving leader. That his supporting cast will be his traditional allies – the far-right and religious parties – only underlines the conflicted attitude to religion in a country that is variously described as the world’s youngest quasi-theocratic republic or an “ethnic” democracy, and suffers the dichotomy of being seen as the “Jewish” state even though most of the world’s Jews are not Israeli.

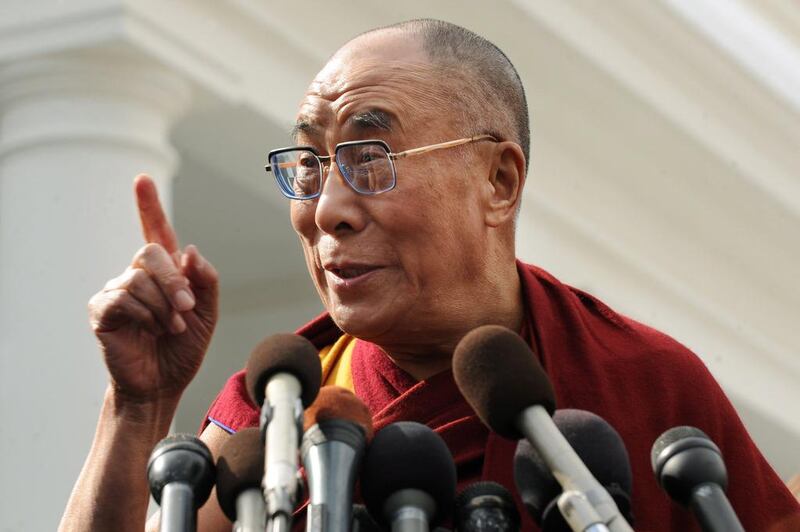

But Israel’s problem with religion is nothing like that of China, which does not officially approve of any dogma other than that of Karl Marx. And yet, the chairman of China’s ethnic and religious affairs committee, Zhu Weiqun, made so bold as to comment a few days ago on the reincarnation of the 14th Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet.

It was rather a comic commentary on Chinese officialdom’s view of the Dalai Lama’s rebirth, an arcane process that involves divining dreams and studying sacred bodies of water.

The Dalai Lama, who led Tibet’s theocratic system until its overthrow by China, fled to India this very week 56 years ago and established a government-in-exile. When he indicated, in a recent interview, that he would not reincarnate and if he did, it would not be in a Tibet that is not free, the Chinese were incandescent. According to an official transcript, Mr Zhu said it was the Chinese government’s place to decide whether or not the Dalai Lama is reincarnated. “In religious terms, this is a betrayal of the succession of Dalai Lamas in Tibetan Buddhism,” he said, adding for good measure that the monk had “taken an extremely frivolous and disrespectful attitude toward this issue. Where in the world is there anyone else who takes such a frivolous attitude toward his own succession?”

A better question might have been who really understands reincarnation in the 21st century, an age when artificial intelligence is being developed and intuitive wearable technology is meant to direct our lives. But the absurdity of Mr Zhu’s comments only serves to underline, yet again, the way that religion is used – and misused – to political ends. In this region, extremist groups like ISIL distort religion in pursuit of a violent political agenda. And Hindu nationalists in India and conservative Christians in the US Republican Party use faith to fight culture wars. That said, it is decidedly unusual for the afterlife to become a political battleground.

It’s obvious that the Dalai Lama’s statement will make it harder for the Chinese government to put in place any plans they might have had to handpick a credible successor, whom they would tout as the 15th Dalai Lama while he would tamely endorse the reality of China’s hold on Tibet. But that is probably why the Dalai Lama said what he did. At 79, he is a wily political operator, having taken charge of Tibet in difficult circumstances aged 16. He clearly wants to safeguard his people against any Chinese “pretenders”.

It is not unusual for religious figures to use their authority for political purposes but does the Dalai Lama’s suggestion that he might not be reborn – breaking a 700-year tradition, possibly for temporal reasons – indicate the secularisation of a position that draws its power from being not of this world?

Might something similar be underway in other faith traditions too? On Sunday, the Catholic pope, Francis, indicated that he felt his pontificate would be brief. “It is a vague feeling I have that the Lord chose me for a short mission.”

Commentary has eddied and swirled around the remarks, some of it conspiratorial and dwelling on a prophecy that purportedly foretells disaster for the Roman Catholic Church, but mostly, there is consternation over new, self-imposed “term limits” for popes, akin to that of an elected president or the chief executive officer of a multinational company. Is this part of a new secularisation of religious office?

God knows, but the current pope’s predecessor, Benedict, resigned in February 2013 after just eight years in a job that is meant to last a lifetime. When the Argentine cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, a Jesuit who lived simply and shunned pomp and show, succeeded him, it was thought that the new Pope Francis would live out his days reforming the Catholic Church.

Two years on, it is clear he has done some of what was required, not least by getting to grips with the Vatican’s finances, long tainted by scandal.

But it sounds like the sort of turnaround any competent CEO would oversee. Consider the slightly jokey verdict delivered by The Economist last year, after Francis's first 12 months in the job. "The business has recovered a lot of its self-confidence," it intoned, because the CEO grasped three management principles: the need to refocus the organisation on one mission (helping the poor); brand repositioning (a less censorious tone on key values) and administrative restructuring.

It was true enough but hardly reverential in the incense-smoke and mirrors way one associates with religion. Does this matter?

Yes and no. There is less risk of fooling the credulous but it does not leave much space – and time – for religious leaders to effect that subtle, transformative process that the British comparative religion writer and former Catholic nun Karen Armstrong described as ethical alchemy.

rroshanlall@thenational.ae

On Twitter: @rashmeerl