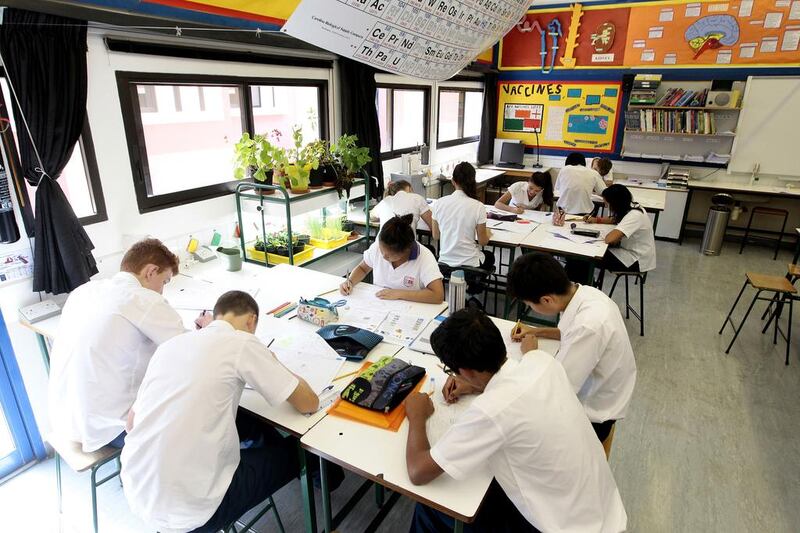

A nationwide moral education curriculum will be piloted at 20 public and private schools in January, with an official roll-out across all schools in September.

As I have mentioned many times in this newspaper, the transmission of Arabic values to the next generation has become disrupted due to employment of foreign housemaids and nannies and less focus on their children from busy parents, among other things.

The UAE is not the only country where the moral education of youth has been transferred to the classroom. Australia, Japan, Sweden and the United Kingdom have all implemented curricula that attempt to inculcate a set of values, usually based upon societal norms and beliefs, religious rules or cultural ethics.

One of the outcomes of moral education is to bring young people to an individual and deeply personal realisation that good behaviour is good for both them and their community.

Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, was briefed on the curriculum in late October. It will be divided into four pillars – character and ethics, individual and community, civic education and cultural education – taught over a six-week period.

Values are mainly learnt affectively through daily interactions with parents, siblings, friends, teachers and people in the wider community – all of whom act as role models for the young generation.

They are not something that can be taught by lecturing with a stern face and a finger pointing upwards in a dire warning of dreadful consequences.

We all teach children values every day in our ordinary daily encounters: how we treat each other in the family, how we manage household staff, how we interact with people in shops and restaurants, and how we manage our emotions when we are under stress.

For example, if a young boy sees his father pick up some rubbish off the street, he may ask: “Why did you do that? You didn’t drop it.” The father may answer: “I don’t know but as it was on the ground, I picked it up and threw it into the rubbish bin.”

The importance of role models cannot be stressed highly enough. From the highest levels of leadership to the people who clean the streets, everyone must understand their role in shaping young people’s perception of what is right and wrong, good and bad, and the “grey bits” in between.

And it is these uncertain grey areas of moral education to which I now turn my attention.

Ethical-dilemma stories have become widely used in science curricula around the world through which students begin to learn of the effect of human decisions on the global and local environment.

Drs Peter and Lily Taylor from Murdoch University in Perth, Australia, have spearheaded the use of these stories through published research and conferences. The stories also provide an excellent learning device for moral education.

Essentially, the story is told freely by the teacher, who pauses at appropriate junctures to pose ethical dilemmas. Students are instructed to engage with each dilemma and make a series of ethical decisions on behalf of the characters in the story.

Let’s look at a simple example.

Your company has a firm policy regarding theft of property. Used company property is sold at an auction each month. One day, you see a senior and valued employee who is only one month away from retirement take an electric drill from the bidding table and place it in the boot of his car before the day of the sale. What do you do?

A key pedagogical aspect of ethical-dilemma learning is that students reflect individually on a question and write down their decision and the reason for making it, thereby engaging with their personal values.

The next step is to interact in small groups to compare and contrast their decisions, thereby promoting critical reflection on their decision-making values.

Teachers have found it best to build up group sizes gradually as students encounter each successive dilemma. Building up group size allows students to “warm-up” to having this type of unfamiliar discourse in class, thereby building rapport and trust.

The main rule of engagement is made clear from the beginning: because there is no single correct answer, it is OK to voice an opinion that is different from that of other students.

Ethical-dilemma stories challenge currently held beliefs and values, often bringing dialectical tension between individual and community beliefs. Children deeply examine their own values and beliefs and engage in social discourse with their peers, so taken-for-granted assumptions are challenged and explored, resulting in a shared understanding of the course of action to be followed.

Two other positive outcomes may arise: emotional learning through promoting active and empathic listening skills when different views are posed in class; and critical problem solving with co-developed suggestions for possible solutions is modelled and actioned.

In conclusion, moral education is vital to the successful implementation of the dream of the Founding Fathers of the UAE. As Sheikh Mohammed recently said: “Our children face major challenges, and it is our responsibility to prepare and protect them. We should not sit back and watch.”

With this new curriculum, the UAE is taking a bold affirmative step in strengthening its next generation.

Dr Peter J Hatherley-Greene is director of learning at Emarise