Earlier this month, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared that any nuclear agreement reached between the P5+1 group and Tehran must include "unambiguous Iranian recognition of Israel's right to exist".

President Barack Obama repudiated such a demand as "a fundamental misjudgement", but that did not dissuade Israel's allies on Capitol Hill from backing Mr Netanyahu.

There are parallels here with Mr Netanyahu’s insistence that the Palestinians must recognise Israel as a “Jewish state” in any potential peace deal.

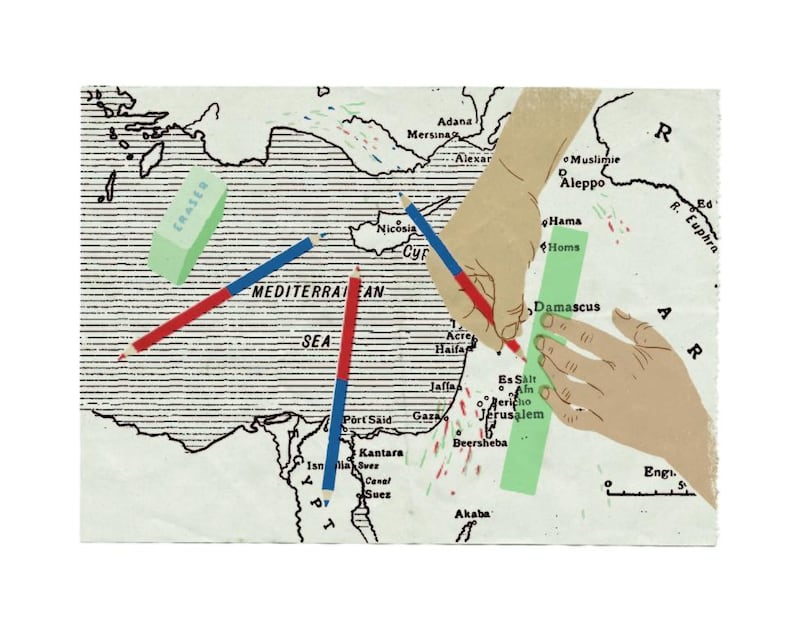

This demand to recognise Israel’s “right to exist” is much more, however, than a negotiations spoiler: it is intended to police the boundaries of acceptable debate, to conceal certain parts of the past and present – and to narrow the options open to Palestinians and Israeli Jews for the future.

This weekend a conference was meant to have taken place at the University of Southampton, under the title “International Law and the State of Israel: Legitimacy, Responsibility and Exceptionalism”.

After months of pressure from pro-Israel groups, however, including allegations of “antisemitism”, threats to funding and the prospect of violent protests, the university administration cancelled the event on “public security” grounds.

According to the organisers, the focus of their efforts was to have been “historical scholarship and legal analysis of the manner by which the State of Israel came into existence as well as what kind of state it is”.

Israel’s supporters, for their part, said the conference would have questioned, or denied, Israel’s “right to exist”, something they see as an illegitimate subject of inquiry.

So let us examine three key elements of this discussion.

First, contrary to the accusations made by the country’s increasingly shrill defenders, Israel is not being “singled out” for such debates. Similar questions are asked in various contexts.

Does Nigeria, fragmented by ethnic and regional tensions, have a right to exist as a single nation? What do Basque and Catalan claims mean for the Spanish state? What would Scottish independence mean for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland?

Across the world, there are live conversations, scholarly and political, about self-determination, nationalism, the legitimacy of states, and the ongoing legacies of colonisation and decolonisation. Why should Israel be exempt?

Not for the first time then, Israel and its supporters are singling themselves out by their intolerance, brittle insecurity and hypocrisy.

Second, there is simply no such thing as a “right to exist” for states. There are rights to self-defence and to territorial integrity, but there is no “right to exist”.

States are created, and states break-up. In just the past 25 years, states such as East Timor, Eritrea, Kosovo and South Sudan have been established and recognised, while others, like Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and the USSR, have joined the long list of former states.

The recognition of Israel’s “right to exist” then, as Noam Chomsky once put it, is an “unprecedented demand”.

Third, self-determination does not equate to statehood. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of ethnic groups, or “peoples”, worldwide; for all of them to realise self-determination through ethno-exclusive statehood is unimaginable.

For Zionists, Jewish self-determination means a “Jewish state” defined by a majoritarian advantage achieved through violent exclusion and dispossession.

Writing in 2003, Israeli jurist Ruth Gavison – recently involved with deliberations over a potential new ‘Jewish nation state’ bill – wrote a defence of “The Jews’ Right to Statehood”.

Here, Ms Gavison is explicit: a “Jewish state” necessarily “limits” the “ability [of Palestinian citizens] to… exercise their right to self-determination.” In other words: “The Jewish state is thus an enterprise in which the Arabs are not equal partners.”

Moreover, Ms Gavison also makes it clear that this “Jewish state” means the permanent exclusion of Palestinian refugees from their homeland, since a return “necessarily means undoing the developments in the region since 1947” – that is to say, the Nakba.

But what if it wasn’t a zero-sum game? By interrogating, and ultimately decoupling, the self-determination equals statehood equation, there need be no contradiction between the return of Palestinian refugees and maintaining the rights of Israeli Jews to self-determination.

Palestinians, too, in the words of a policy brief by the journalist Ali Abunimah, are examining “the need to distinguish the limited goal of sovereignty from that of self-determination”.

“Self-determination may result in a sovereign state – but it may not,” Abunimah wrote. “It is fundamental to understand this difference and to recognise that self-determination remains at the heart of the Palestinian struggle.”

In recent times, these kinds of questions have started to penetrate mainstream discussions (contributing to Israel’s sense of panic and talk of so-called “delegitimisation”).

In 2013, for example, philosophy professor Joseph Levine wrote in The New York Times: "Far from being a natural expression of the Jewish people's right to self-determination, [Israel as the Jewish state] is in fact a violation of the right to self-determination of its non-Jewish (mainly Palestinian) citizens."

Levine, rejecting both the idea of Israel as a “Jewish state” and the accusation that to do so is somehow anti-semitic, expressed support for a state “based on civic peoplehood”, a democratic state that “respects the self-determination rights of everyone under its sovereignty” – that is to say, a “state of all its citizens”.

Palestinian scholar Nadim Rouhana has written how “the right of the Israeli-Jewish people to self-determination” does not require “a solution based on partition” – a two-state solution.

In addition, the rights of Palestinians in Israel and a just solution to the refugees’ problem, “lead to the direction of bi-nationalism inside Israel.”

Therefore, Rouhana, asks, “why should Israelis and Palestinians not start thinking about alternatives to partition?”

Return of the Palestinian refugees and civic not ethnic self-determination are the foundations of this alternative.

The late writer Mike Marqusee said it was “extraordinary” how the demand to recognise Israel’s right to exist, “so often repeated”, was also “so rarely subjected to scrutiny”.

Despite the best efforts of the state of Israel, with its supporters and allies, these questions are being asked more frequently, and more insistently. It is imperative that we continue to do so.

Ben White is a journalist and the author of Palestinians In Israel: Segregation, Discrimination and Democracy

On Twitter: @benabyad