‘It’s the economy, stupid,” was the motto of Bill Clinton’s winning 1992 US presidential campaign, signalling an awareness that even military success against Saddam Hussein would not protect George H W Bush from the wrath of voters squeezed by rising unemployment.

Today's Democratic presidential hopeful, Hillary Clinton, won't be able to capitalise on the economy in the way her husband did 24 years ago, not only because of her insider status, but because she has campaigned all along as the candidate of continuity with the Obama administration status quo.

A different story

In response to Republican candidate Donald Trump's "Make America great again" rhetoric, Mrs Clinton declares: "America never stopped being great." But Mr Trump would be nothing more than a sideshow barker if his rhetoric didn't resonate with white working-class voters whose living standards have steadily declined over decades.

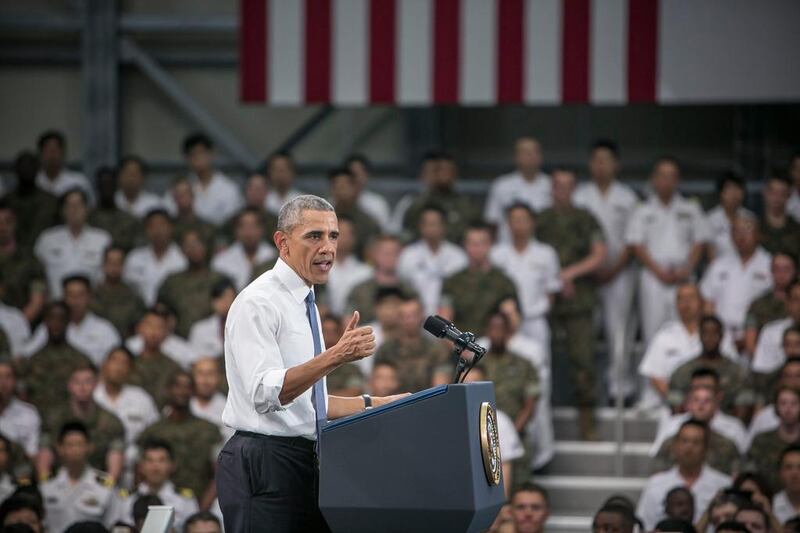

That's not the story being told by the political establishment of which Mrs Clinton remains an integral part. Mr Obama dismisses negative judgments on his economic performance, telling The New York Times that given the scale of the 2008 crisis, "we probably managed this better than any large economy on Earth in modern history". But it remains the slowest recovery since the Second World War, and most of its benefits have gone to a tiny elite.

As economics Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz recently explained: “In the first three years of the recovery, 91 per cent of all gains went to the top 1 per cent. So the bottom 99 per cent saw nothing. Many were actually becoming worse off.”

So it was, too, with the government’s infusion of cash into capital markets. Because most Americans had little stake in the stock market, Mr Stiglitz called it another “gift to the 1 per cent”.

Mr Obama’s jobless recovery is not particularly surprising, given the framework in which he has managed the economy – like George W Bush and Bill Clinton before him – is based on neoliberal free-market orthodoxy, which renders taboo the traditional Keynesian remedy for stagnation – that is, expanding government spending to boost aggregate demand while addressing social needs.

As president, Mr Clinton embraced Ronald Reagan’s goals of shrinking government, dismantling the welfare state and deregulating financial markets and international trade. This created a bipartisan consensus that has created an economy that works predominantly for a wealthy minority.

Much of the growth Mr Obama touts has occurred in the financial sector, which no longer fuels job creation. As Time analyst Rana Foroohar has argued, the "financialisation" of the US economy means that today, only about 15 per cent of money invested by capital markets comprises traditional business investments that drive job growth. Most of the rest is speculative investment, creating asset bubbles and deepening inequality.

Making money

Many of the biggest US corporations today make more money from moving money around than they do from the products and services they sell.

Financialisation, she says, is the reason that $4 trillion (Dh14.7tn) in monetary stimulus under Mr Obama has fuelled little job growth.

The success of Mr Trump has begun to sound alarm bells within the political establishment – precisely because the economic orthodoxy on which it has relied for a generation offers no remedies to a stagnation that threatens political stability.

Markets alone won’t fix the inequality and resultant stagnation threatening much of the global economy, and cutting interest rates has proven ineffective. And with interest rates already near zero, it’s not a viable response to a new recession that may be looming.

State spending

Democrat candidate Bernie Sanders’s policy proposals focused on taxing billionaires to fund state spending on infrastructure, education and health, were pooh-poohed as the stuff of fantasy. When economic historian Gerald Friedman ran Mr Sanders’s proposals through orthodox models and concluded they’d create 5 per cent GDP growth, he too was vociferously denounced by economists associated with the Clinton campaign and Obama administration. Their message is that today’s anaemic growth is as good as things could be.

“If nothing much can be done, if things are as good as they can be,” wrote Friedman in response, “it is irresponsible even to suggest to the general public that we try to do something about our economic ills. The role of economists and other policy elites … is to explain to the general public why they should be reconciled with stagnant incomes, and to rebuke those, like myself, who say otherwise before we raise false hopes that can only be disappointed.”

In a bizarre admission of her campaign’s lack of new policies, Mrs Clinton told a crowd in Kentucky that she would put her husband “in charge of revitalising the economy, because, you know, he knows how to do it”.

That message drew groans even from supporters, not least because so much of what Mr Clinton “knew how to do” in the 1990s has set the stage for the dire economy of today. Even some Clinton-friendly economists such as former Treasury secretary Larry Summers are warning that without some substantial policy rethinking, the economy isn’t going to revitalise. The political consequences of long-term stagnation are becoming frighteningly clear across the industrialised world.

Tony Karon teaches at the New School in New York

More from this author:

■ It's all about the economy and it's not good news

■ US needs to talk about its nuclear intentions