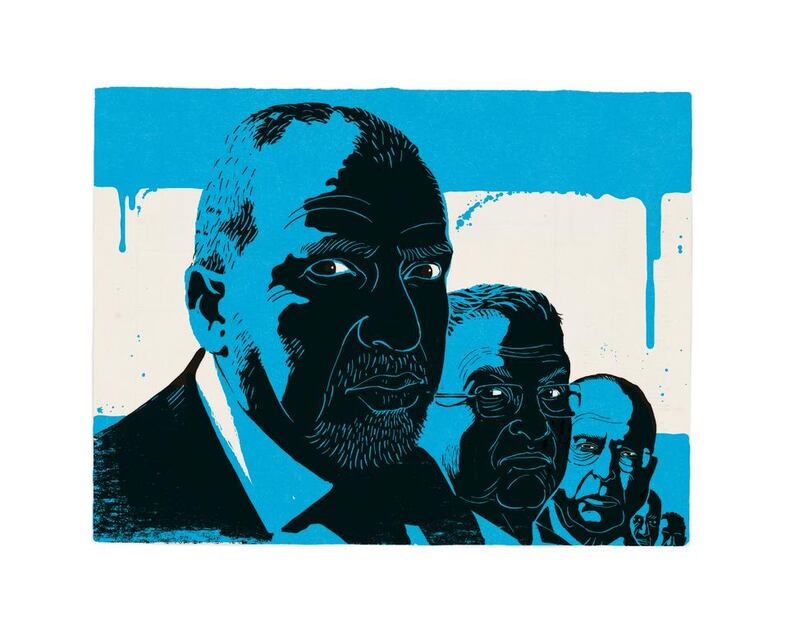

Last Monday’s swearing in of the ultranationalist politician Avigdor Lieberman as Israeli defence minister has sparked much controversy inside and outside the country.

The media is describing the new government as “the most right-wing in Israel’s history”. However, we have heard this phrase so many times in recent years that it has lost its meaning and potency.

Furthermore, the statements of concern within Israel and around the world give the false impression that Mr Lieberman’s appointment has poisoned an otherwise moderate Israeli polity. Never mind that his political career dates back to the 1980s, and that his rise in popularity and posts in various governments would not have been possible without his endorsement by a steadily and increasingly hard-line Israeli society.

Mr Lieberman’s credentials are certainly alarming. Among other things, he has called for the execution of Palestinian members of Israel’s parliament, the drowning of Palestinian prisoners in the Dead Sea “since that’s the lowest point in the world”, and the bombing of Egypt’s Aswan Dam. He has also made comments that have been widely interpreted as advocating a nuclear attack on the Gaza Strip, and the beheading of Palestinian citizens of Israel.

So far, two high-profile Israeli politicians, former prime minister Ehud Barak and outgoing defence minister Moshe Yaalon, have sounded alarm bells over Mr Lieberman’s appointment to a post they have both previously held.

“What has happened is a hostile takeover of the Israeli government by dangerous elements,” said Mr Barak, adding that the country has been “infected by the seeds of fascism”. Mr Yaalon warned that “extremist and dangerous elements have overrun Israel”.

However, neither politician has a moral leg to stand on. When he was prime minister, Mr Barak said: “The Palestinians are like crocodiles, the more you give them meat, they want more.” As defence minister he led the 2008-2009 invasion of Gaza, which killed more than 1,400 Palestinians, the vast majority of them civilians.

That attack was the focus of Mr Yaalon’s tenure as chief of staff of Israel’s army, including Operation Defensive Shield, the largest military assault on the West Bank since the 1967 war.

As defence minister, Mr Yaalon said in 2009: “Regarding the issue of the settlements, in my opinion Jews can and should live everywhere in the land of Israel.” Last year, he said: “I am not looking for a solution. I am looking for a way to manage the conflict in a way that works for our interests. We need to free ourselves of the notion that everything boils down to only one option called a [Palestinian] state.”

Mr Yaalon threatened to “hurt Lebanese civilians to include the kids of the family” in any future conflict against Lebanon. “We did it in the Gaza Strip. We are going to do it in any round of hostilities in the future.”

The irony is that in their actions and statements, Mr Barak and Mr Yaalon (and others) have directly contributed to the very fascism and extremism they are warning against. As such, Mr Lieberman is in good company rather than an anomaly in Israeli politics. “In Israel, politics is much more familiar than any other place. We all know each other,” said Mr Barak. How right he is.

Indeed, repeated use of the term “most right-wing government in Israel’s history” falsely implies that it is only the right wing that has contributed to the injustices inflicted on the Palestinians, and the danger Israel poses to the wider region. Leftist and centrist governments have been just as oppressive and aggressive. There may be differences in style, but not in substance.

All Israeli governments, regardless of ideology, have zealously entrenched the occupation and colonisation of Palestine. The barrier snaking its way through the West Bank, which is widely associated with right-wing prime minister Ariel Sharon, was in fact the brainchild of his leftist predecessor Mr Barak.

Regarding Lebanon, Israel’s 1982 invasion was launched by right-wing prime minister Menachem Begin, Operation Grapes of Wrath in 1996 was launched by leftist premier Shimon Peres, and the 2006 war took place under the centrist Ehud Olmert.

Developments from the last several months alone amply demonstrate how extreme Israel’s politicians and society have become – all before Mr Lieberman’s return to government – to the extent that it has become alarmingly normal. Last month, a Likud source said a new law would apply the death penalty to non-Jews only.

In February, prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced his intention to “surround all of Israel with a fence” to protect the country from infiltration by Palestinians and citizens of surrounding Arab states, whom he described as “wild beasts”.

In December, the education ministry banned members of Breaking the Silence, who publicise abuses they have seen or carried out during their military service in the occupied Palestinian territories, from engaging with schools. That same month, the ministry also banned from high schools a novel about a love story between an Israeli and a Palestinian.

Israel’s parliament passed a new law that jails Palestinian stone-throwers for up to 20 years, with a minimum of three years. The move was perversely described as “justice done” by Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked, notorious for a Facebook post saying all Palestinians are “the enemy”, and Palestinian mothers should be killed otherwise “more little snakes will be raised”.

These policies and statements are shocking enough without considering that the politicians responsible are elected. When the public endorses such radicalism, what incentive do their representatives have to be moderate? As such, the problem goes way beyond Mr Lieberman and even Israeli politics, to Israeli society itself.

Last month, Israeli army deputy chief of staff Yair Golan drew comparisons between his country today and “the revolting processes that occurred in Europe in general, and particularly in Germany, 70, 80 and 90 years ago”.

He is right to be so concerned. An opinion poll in March revealed that almost half of Israeli Jews believe Israel should be ethnically cleansed of Arabs, and 80 per cent say Jews deserve preferential treatment to non-Jews. There is a term for that: apartheid.

In December, video footage emerged of Israelis dancing at a wedding with guns as they stab a picture of Ali Dawabsheh, a Palestinian toddler murdered in a hate crime carried out by settlers. That same month, Benzi Gopstein, head of the far-right Lehava organisation, said Christmas should be banned, and called Christians “vampires and bloodsuckers”.

Mr Lieberman is not just part of the problem, but a symptom of it. So too, however, are most of his Israeli peers, some of whom seem to think that by scapegoating him they can wash their own bloodstained hands, and clear their consciences of the injustices they have supported and the extremism they have fostered.

Feigning concern and giving the problem a more nuanced facade will only make it worse. This is opportunism, not morality.

Sharif Nashashibi is a journalist and analyst on Arab affairs