Browsing the Middle East section of the BBC news app can be a depressing business, as a random selection of recent headlines makes clear. “We escaped after ISIL stormed house”, “Caught in the crossfire in Mosul”, “Too scared to use refugee camp toilet”, “Syrian photographer puts down camera to rescue child”, and so on and on.

This is the distorting lens through which much of the rest of the world views the region, a world for which the very words “the Middle East” have become synonymous only with war, religious extremism, suffering and death.

It would, of course, be foolish to pretend that all parts of the region are free of these things. But there is so much more to life in each of the countries that comprise the Middle East that never penetrates the consciousness of western news consumers.

This matters, especially at a time when European countries are enduring a rash of so-called “lone wolf” attacks, carried out by deranged social misfits misguidedly seeking to imbue their hopeless lives with some kind of higher meaning by claiming allegiance to an Islamic extremism of which they have very little real understanding.

It matters because the increasing perception in the West of Muslims only as dangerous “others” is fuelling the resurgence of the sort of narrow-minded, xenophobic bigotry that is shifting in dangerous directions political tectonic plates from Washington to London and beyond.

It matters because dehumanising people, reducing millions of individuals to a negative stereotype, makes it easy to hate, fear and despise them – and that, as not-too-distant history has shown, makes it easy for supposedly civilised societies to attack and kill them in large numbers, without any societal compunction or moral qualms.

In theory, thanks to the potentially unifying mechanisms of the modern world, such as air travel, the internet and the spread of a globalised meta-culture, the world is smaller than it has ever been. But, counter-intuitively, this has not made us into one big happy family.

Yes, “ordinary” people can fly to once exotic locations for their holidays, but they holiday in comfort-zone bubbles, cut off from real people, and arrive and leave with preconceptions undisturbed.

The internet, which early pioneers naively theorised would bind us through a sense of community, serves only to herd us into insular self-interest groups, facilitating the spread of fake-news propaganda to reinforce fears and prejudices.

As for global culture, the reality is a western-dominated version of the world, complete with stereotypes, projected through film and other mass entertainment media.

When Hollywood comes to the Middle East, it does so only to stage “exotic” car chases or cinematic drone strikes, always prefaced by the same shorthand shots of sand dunes and camels, set to an Arabian Nights-style soundtrack. Imagine if the establishing shot of every film set in London, regardless of plot or time period, were accompanied by a few bars of Edward Elgar’s Nimrod?

The potential consequences of this drawbridge mentality are immeasurable. The future of a planet faced with challenges ranging from escalating global population growth to climate change and terrorism depends above all on collaboration, the bringing together of political will, understanding and scientific expertise from wherever it may be found.

However, as is clear from political developments in America, the United Kingdom and France – where the fact that far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen has made it through to the final round of voting on May 7 reveals the vulnerability of liberal values – politicians cannot be trusted to dismantle the barriers of prejudice and ignorance holding back the unity the world needs so badly.

The tragedy of this is that, when left to their own devices and not being morally and emotionally misdirected by powerful, self-serving agendas, by and large ordinary people get on just fine, regardless of history, religion, race or colour. Evidence of this can be found in the exploits of two remarkable western women, separated by a century but united by a courageous and exemplary brand of open-mindedness.

At first glance there is little commonality between Rebecca Lowe, a British former legal reporter who has just completed an eccentric solo cycling tour of Middle Eastern countries, including Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, the UAE and Iran, and Gertrude Bell, the extraordinary British woman who during and after the First World War played a key role in shaping much of the Middle East as we know it today.

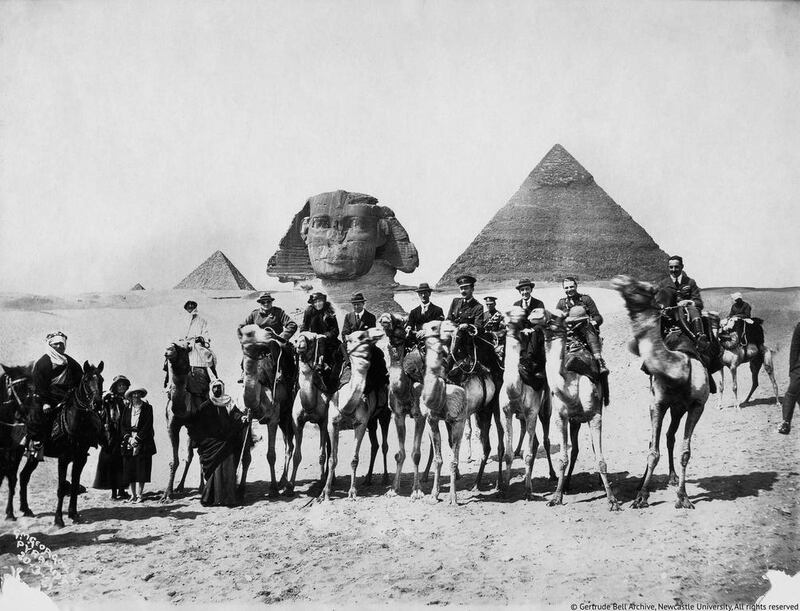

Like T E Lawrence “of Arabia”, whom she came to know well, Bell, who was born into privilege in England in 1868 and died in 1926 in Baghdad, where she is buried, traded up her pre-war interest in archaeology and Arabia to become a vital cog in the machine of British imperial policy in the Middle East.

Today, Bell is often blamed for many of the woes of the region for the part she played in moulding Iraq from the remnants of Ottoman Mesopotamia. But, as the film Queen of the Desert, starring Nicole Kidman, makes clear to a wider audience, in her travels throughout the region Bell came to know, love and respect the Arabs, bonding with humble tribesmen and sheikhs alike over campfires and in majlises.

Upon the foundations of that respect, in the words of Georgina Howell, the author of the book upon which Werner Herzog’s film is based, she “cajoled … guided and engineered, and finally delivered the often promised and so nearly betrayed prize of independence … Bell stuck to her ambition for the Arabs with a wonderful consistency”.

In Bell’s wake follows Rebecca Lowe. It would, of course, be fatuous to compare Lowe’s Tour d’Arabie with Bell’s lifetime of dedication to the interests of the Arab people, often in the teeth of the disapproval of her own countrymen. But although vastly different in scale and purpose, each woman’s achievements were built on a fundamental determination not to be dictated to by prevailing prejudices and to be their own judge of the characters of people as individuals.

Lowe wrote about her 10,000-kilometre odyssey, which began in 2015, in an article for the BBC published earlier this month.

It made a refreshing change to the usual doom and despair. Her aim was to “shed light on a region long misunderstood by the West … to show that the bulk of the Middle East is far from the volatile hub of violence and fanaticism people believe”.

Friends believed she would die. One man told her she was “a naive idiot who would end up decapitated in a ditch”. In fact, far from losing her head, Lowe found friendship and kindness wherever she went, offered by strangers sharing water, lifts and lodgings.

“Throughout the Middle East, it was the same,” she wrote. “Doors were forever flung wide to greet this strange, two-wheeled anomaly who was surely in need of help, and possibly psychiatric care.”

Her hosts included the “rich and poor, mullahs and atheists, Bedouin and businessmen, niqab-clad women and qabaa-robed men”. Each person and community she encountered was different, “but certain traits linked them all: kindness, curiosity and tolerance”.

World leaders are busy people. But how much better – how much more humane – the world might be if they could be persuaded to get on their bikes and meet the real people behind the stereotypes so easily and cynically invoked in the name of divisive politics and votes.

As Bell and Lowe both discovered in their own way, it is hard to demonise, let alone bomb, a person who has given you water in the desert, or food and shelter for the night.

Jonathan Gornall is a frequent contributor to The National