When Khairuldeen Makhzoomi boarded a flight from Los Angeles this month, he was excited about the dinner he had attended the night before. The 26-year-old student called his uncle in Baghdad to tell him how Ban Ki-moon had addressed the gathering, and that he had actually managed to ask the United Nations secretary general a question. Unsurprisingly, given that Mr Makhzoomi and his uncle are both Iraqi, their phone conversation was in Arabic.

Mistake. Mr Makhzoomi was swiftly ejected from the plane and grilled by FBI agents about “what you said about the martyrs”. A fellow passenger, alarmed by the sound of Arabic, picked up on the world inshallah – God willing, one of the most frequently used phrases in the Muslim world – and assumed that Mr Makhzoomi was about to blow up all those aboard.

Mr Makhzoomi may have come to the United States as a refugee, his father, a diplomat, having been jailed and then killed under Saddam Hussein’s regime. But as an employee of the airline is reported to have said: “Why are you talking in Arabic? You know the environment is very dangerous.”

Many people have encountered the indignities sometimes associated with “flying while Muslim” – or appearing to be. My wife and I were once part of a group late for a flight to Miami. If we were quick, we could still board, and all of us were ushered through – apart from my wife. She was not allowed on the flight. Was it any coincidence that the rest of us were Caucasian, but she is Asian with a Muslim name? The airline wouldn’t say.

At least that was better than the experience of a former colleague at a British newspaper who flew to New York on the visa-waiver programme. Ah, but he was a journalist and he didn’t have a media visa (which no one used to bother with), he was told – and put on the first flight back to London. At the paper, hardly anyone doubted that his Pakistani Muslim heritage and name just might have had something to do with it.

Those two incidents were both about 15 years ago, and in the aftermath of the events of September 11, 2001. Despite the admirable declaration by president George W Bush that “Islam is peace”, fear and tensions ran so high that a petrol station owner was killed by an American determined “to go out and shoot some towel heads”. It didn’t matter that the victim was Sikh, not Muslim.

Since then, however, large amounts of time and money have gone into programmes, publications and organisations that have attempted to reduce misunderstanding between different faiths. The United Nations Alliance of Civilisations was established in 2005, its mission “to explore the roots of polarisation”.

Malaysia’s prime minister, Najib Tun Razak, launched the idea of a Global Movement of Moderates at the UN General Assembly in 2010. The Coexist Foundation, based in Washington, DC and London, counts the former grand mufti of Egypt and the former chief rabbi of Ireland among its board members.

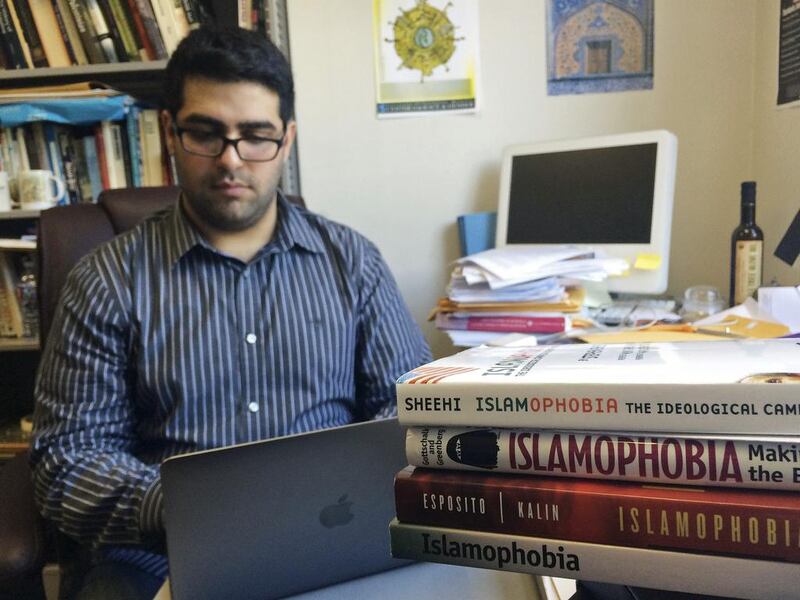

Much good work has been done and some very useful scholarship produced. But it is clearly not enough, and it is not reaching the right people. Among the vast majorities who have no connection to such initiatives, fear, misunderstanding and hatred have only increased.

A poll last December found that 61 per cent of Americans had an “unfavourable” opinion of Islam – up from 39 per cent in October 2001. In the UK, 55 per cent of voters believe “there is a fundamental clash between Islam and the values of British society”. Only 22 per cent said they were “generally compatible”.

There is no trickle down – or none that can be discerned – from the gatherings of admirable, but like-minded, elites. Islamophobia is rife in Europe and America. This matters not just because any kind of intolerance is to be deplored. It is an active recruiting tool for extremists such as Al Shabab, which included footage of Donald Trump in a video released in January.

Mass public information campaigns are needed to overcome the prejudices of the millions who have been bombarded with negative stereotypes of Muslims, from the countless action movie villains to the pontificating of liberal commentators who know just enough about Islam to be convincing when they caricature the most extreme – and, in fact, un-Islamic – interpretations of the religion as the only genuine ones.

There was a wonderful campaign in London a few years ago in which posters went up on double-decker buses and taxis with ordinary men and women standing above captions including “I believe in women’s rights. So did Mohammed” and “I believe in protecting the environment. So did Mohammed”. It was a revelation to the many who had never thought about the Prophet and Islam in such a light. Unfortunately, it was short lived.

Simple, relatable images and role models are desperately needed to show people like the woman who objected to the young man speaking Arabic on a plane that Muslims are just like them.

Would she, too, not have wanted to phone her family in excitement if she had met the UN secretary general? Would she, too, not have been furious to have been forced from the plane, merely for making the call in her mother tongue?

But the poison that Muslims are “other”, alien implants in western soil, has spread far and deep. We cannot rely on theologians and academics to provide the antidote. It is time for governments to take a lead in insisting on our common humanity. For it is that alone that will save us from extremist purveyors of death – in whoever’s name they claim to act.

Sholto Byrnes is a senior fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia