‘If I don’t do well on this test, then I’m not going to a good middle school and if I don’t go to a good middle school, I can’t get into a good high school, and then I won’t get into a good college, and I’m going to end up living in a box in the subway.” That was the apocalyptic vision of the 10-year-old daughter of a friend of mine, on the eve of what were (in her mind, anyway) the do-or-die “fourth grade tests” in New York City. The test results dictated where children would be allowed to apply in sixth grade, an arcane logic that makes sense only to the New York City Department of Education.

Every year, when the end of the school year comes around, with its accompanying tests and exams, I remember that little girl drawing a straight line from her standardised test performance to living in a box. Even though the school that she and my son attended tried to tell the children not to stress about the tests, the message to relax was delivered so insistently that my son said: “Should I be worried?”

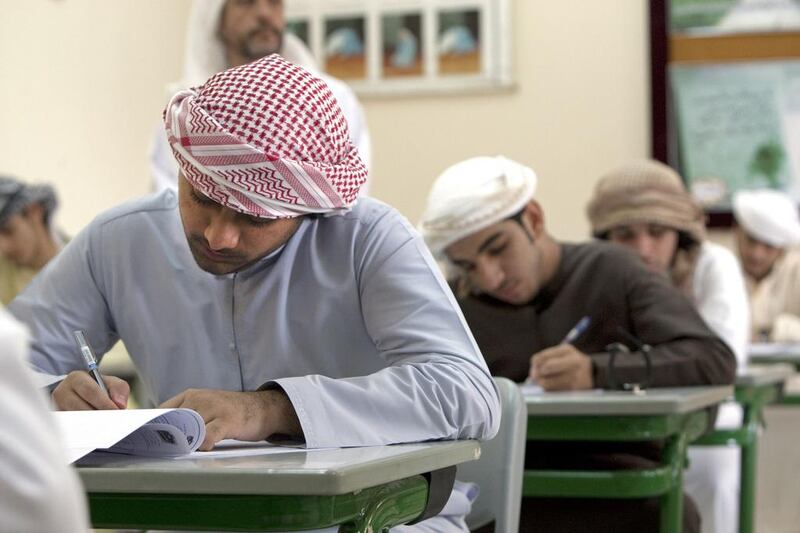

NYU Abu Dhabi just graduated its third cohort of students, which means the preceding weeks were crammed with races against the clock to meet final-project deadlines. Children all over Abu Dhabi are doing their exams now, to finish before Ramadan. Testing, it seems, is in the air, and although my children would, of course, never ask this question, I hear that in other households, children are asking why they have to bother with all these tests. My children, of course, happily revise for hours and trot off, smiling, to their exams.

But maybe it’s not an unreasonable question. What use are all these tests? A class-based exam may measure the degree to which children have gained certain competencies and where they may still be struggling, but does that exam offer a full picture of student achievement?

As someone who has spent more than two decades in the classroom, I have to say that I wish exams captured the entire picture of the student because then my job would become infinitely easier: hand out a test, mark the answers, and voila, that number equals the entirety of that child’s career in the course.

Alas, we don’t learn in a straight upwards curve, we learn in dips and swerves, loops and digressions. Assessment, then, if it is to be an accurate portrait of a student, needs to see as many facets of the student as possible – and of course, that takes time (and time, as we all know, is also money).

The complexity of assessment has given rise to a multibillion dollar international testing industry – and perhaps it will not surprise you to learn that the assessment industry does not deal well with complexity.

Here’s a quiz for you: what does the standardised testing industry claim for its tests? Do the tests: (a) measure student achievement; (b) measure teacher effectiveness; (c) measure a school’s overall performance; (d) measure a headmaster’s overall effectiveness; (e) influence future school budget allocations; f) promote multibillion dollar international business; or (g) do all of the above?

If you chose the last option, you’re right. Now ask yourself: how can one test, or even a battery of tests, achieve all of these different (and sometimes competing) aims?

Complexity is difficult, a three-hour multiple-choice test is easy. Many educational experts, however, agree that student achievement on these tests demonstrates … how good (and how prepped) the student is at taking the test.

I suppose it’s not a coincidence that as testing industry has grown, so too has the test-prep industry, to the point that if I lived in Manhattan, I could probably earn as much (or more) money as a test-prep tutor than as a literature professor.

We live in a world of daunting complexity, with problems that demand imaginative, out-of-the-box thinking. Why then are we measuring our kids’ abilities using tests that teach them to fill in the box?

Deborah Lindsay Williams is a professor of literature at NYU Abu Dhabi