Whether in school, college or the workplace, I find grading degrading. I’m an education professional, an associate professor no less.

However, towards the end of each term I start to think of myself as a grubby little grade trader.

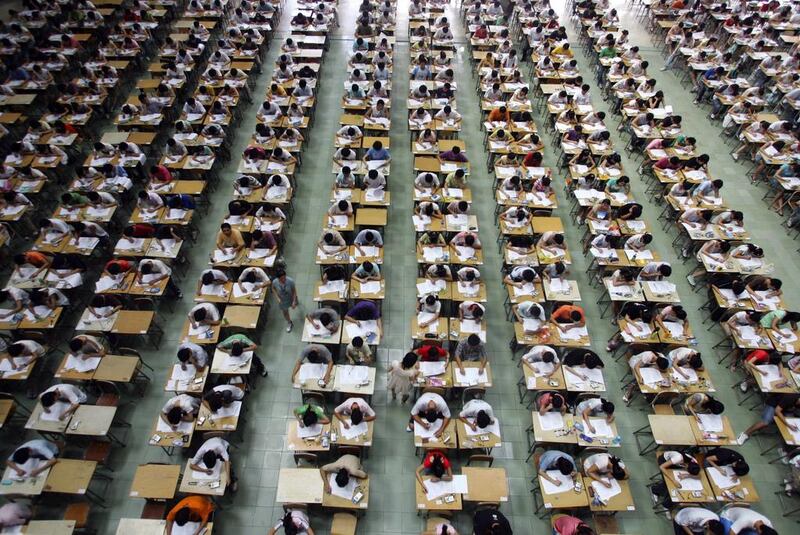

At this time of the year, it seems like our universities, these esteemed engines of civilisation and progress, are reduced to the academic equivalent of frenzied fish markets. The must-have catch of the day for most students is the coveted A grade. I call the last day of the academic year Black Thursday; this is when grade negotiations, remonstrations and outright grade rage reach an ugly peak.

Forget grades though, education should be about the acquisition of knowledge, growth promoting experiences and learning how to learn. Unfortunately though, these days, it seems to be increasingly all about the grades.

This state of affairs is hardly surprising. We have come to over-rely on grades – A through F – to encourage and threaten students, driving many young minds to the verge of academic neurosis. Some educators brandish the threat of a D grade like a bullwhip in the hands of an overzealous plantation overseer. Within such a context some students become no more than grade slaves, working just hard enough to avoid the sting of a low grade.

The test for differentiating intrinsically motivated seekers of knowledge from extrinsically motivated grade slaves lies in the answer to the following dilemma.

Professors 1 and 2 deliver two sections of the same course. Prof 1 is reputed to be great at imparting knowledge, but a tough grader, while prof 2 isn’t such a great teacher, but is known around campus as an easy A. Which one would you opt to take the course with?

Our current overemphasis on letter grades creates an unhealthy climate of competition, undermining the academic ideals of development and cooperation. Grades also encourage students to make peer-comparisons rather than self-comparisons. I know students who are content, just so long as they get a higher grade than so-and-so.

Ultimately though, these letter grades are pretty meaningless Is an A from prof X at school Y, the same as an A from prof Y at school X?

In the US, the grade point average (GPA, the average of all grades received) is often taken as some kind of universal currency of academic worth and employability. It isn’t. We have compromised precision for an illusory standardisation.

The emphasis on grades and the perceived relationship between GPA and future opportunities, earnings and success, creates massive pressure for “good grades”.

Perhaps this pressure has contributed to the rampantly rising academic dishonesty reported by many universities? From plagiarism to buying papers online this behaviour undermines the very foundations of the education system. Some of our students have become too grade-obsessed.

But what could replace the letter grades we have become so dependent upon?

There are several alternatives; the one I particularly like is the idea of behaviourally descriptive standards-based assessment. Under this system you can either do the thing – speak Arabic fluently, for example – or you can’t. In its simplest incarnation this is pass or fail, kind of like the driving test.

In addition to shifting to a mastery-based system, it would be great to promote the idea of education for its own sake, rather than education as a means to a salary.

I am privileged to know many students who epitomise this ideal; those who still have that natural childlike yearning for learning. Unfortunately, unless we reform our education system such students will become increasingly rare.

Dr Justin Thomas is an associate professor of psychology at Zayed University

On Twitter: @DrJustinThomas