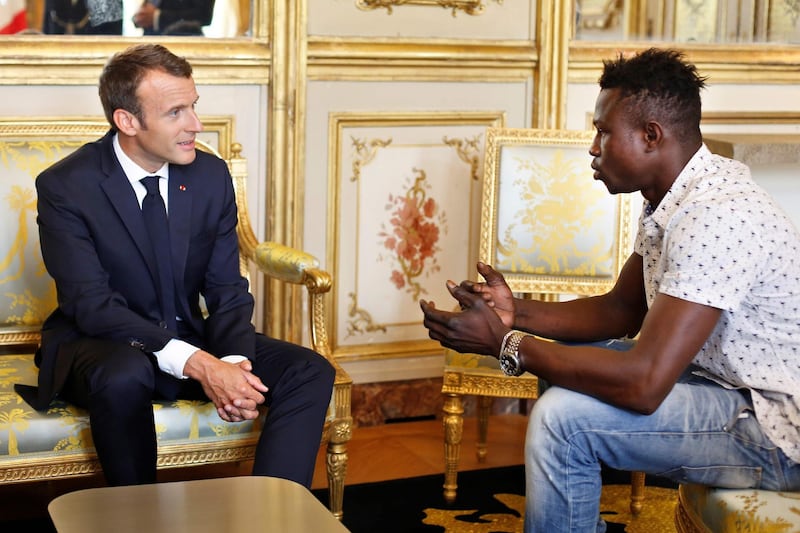

When he saw a four-year-old child dangling precariously from a balcony, Mamoudou Gassama did not give his own safety a second thought. He immediately and effortlessly scaled four storeys of the Parisian building to rescue the child. The 22-year-old Malian migrant was rewarded with an audience with French President Emmanuel Macron, a job as a firefighter, praise from Paris's mayor and an offer of French citizenship. After an exceptional act of bravery, Mr Gassama fully deserves his plaudits. So too did his compatriot, Lassana Bathily, who was given a French passport in 2015 after saving six lives after an ISIS-affiliated terrorist stormed a Parisian supermarket. But while their incredible derring-do should rightly be lauded, it is worth remembering not everyone who finds themselves needing shelter is capable of carrying out such an act, nor should it be a measure of worthiness. Today in Europe there are hundreds of thousands of migrants, as well as refugees fleeing war in Syria and elsewhere. Like Mr Gassama, they are looking for a better life, whether that means improved conditions, opportunities or safety. Often voiceless, invisible and endlessly waiting to improve their circumstances, they are no less deserving of citizenship.

France alone received more than 100,000 asylum applications last year, according to the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons. Across Europe, more than one million migrants and refugees arrived by sea in 2015, according to UNHCR, the UN's refugee agency. Yet in their desperate bid to improve their fortunes, at least 4,000 people drowned in the battle to get there. Many endure a horrific ordeal en route. During his own journey, Mr Gassama was beaten and detained in Libya for a year. Most who arrive are then treated with suspicion or outright hostility – sentiments that, in an increasingly populist Europe, are becoming enshrined in public policy.

Hungary this week is considering implementing new laws to penalise NGOs who help asylum seekers and migrants with food and legal advice. Prime Minister Viktor Orban is pushing for the Stop Soros bill amid claims "Muslim invaders" are a threat to sovereignty. Meanwhile, Austrian lawmakers plan to cut benefit payments for migrants and refugees and in France, despite Mr Gassama's laudable treatment, a controversial immigration bill doubles the period illegal migrants can be detained to 90 days and introduces one-year prison terms for illegal entry. The rise in anti-migrant rhetoric should give us all cause for concern. For while the turnaround in Mr Gassama's fortunes is to be praised, it is worth remembering that he is one of the largely invisible millions, many of whom will never get an audience with a president to plead their case.