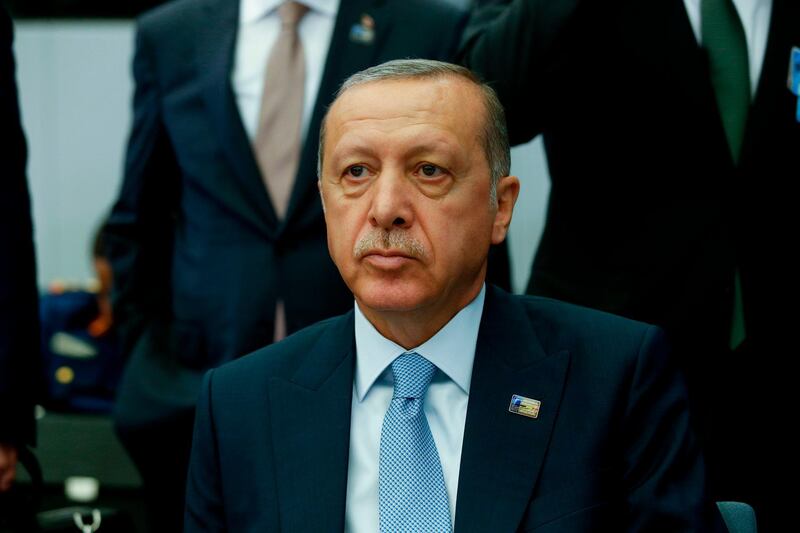

Last month Turkey rounded off the biggest constitutional overhaul since the foundation of Ataturk’s modern republic. At its summit sits Recep Tayyip Erdogan, its virtually omnipotent president, holding the country in his vice-like grip.

Yesterday marked the two-year anniversary of an attempted coup that plunged Turkey into chaos, triggering a state of emergency under which thousands were jailed – and many more lost their livelihoods. And thanks to a narrow referendum last year and fresh elections last month the autocrat now has total power in a presidential system.

Accusations that Mr Erdogan has used his office to muzzle his opponents are increasingly hard to refute, while he has used a narrative of “Turkey under siege” to build support across the country. Two years on from the coup, Turkey is almost unrecognisable.

And with each new presidential decree, the country takes a new stride away from the European democracies on which it once sought to model itself.

Yet there remains one bastion of dissent over which Mr Erdogan has little authority: international markets. Last week, the Turkish lira plunged to a record low against the US dollar, capping its biggest weekly slump since 2008. Its unenviable position as the globe's worst-performing currency has raised fears of an all-out currency crisis.

High inflation and unemployment alongside a deteriorating current account deficit are equally troubling. By some estimates, Turkey needs to lure $200 billion a year in foreign financing to stay afloat.

Worse still, much of Turkey’s economic malaise is self-inflicted. As he has amassed greater and greater powers, Mr Erdogan has disregarded calls for the important structural reforms that would soothe investor confidence.

Instead, the president has pursued a head-scratching monetary policy – founded on his unique belief that high interest rates encourage inflation. While analysts are united in calling for a period of calm, most expect Mr Erdogan to push for lower interest rates in search of rapid growth. His strategy of presenting economic decline as conspiracy by the West to smother Turkey’s progress will insulate him. But long term decay could well expose chinks in his armour.

And a fresh crisis hit markets last week, when Mr Erdogan appointed his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, as Turkey’s finance minister, demoting nimbler economic minds.

He also passed a decree allowing him to directly appoint the governor of Turkey’s central bank, an institution that looks less autonomous by the day.

Such cronyism isn't out of character, but while his power is almost limitless within Turkey, Mr Erdogan's arm does not extend to international markets. And for now at least, exactly two years after the coup that cemented his dominance, the country's economic credibility lies in tatters.