Iraqis are ready for change. They said so in the first election held since ISIS was driven out of Iraq, when they voted emphatically in favour of those fighting corruption. And they said so by staying away from polling stations, with more than half the population feeling disenfranchised enough not to vote. It was influential cleric Moqtada Al Sadr who won the day by running on a platform of upholding Iraq's sovereignty against Iranian assaults, eradicating corruption and terminating the practice of awarding ministries along sectarian lines. His bloc Sairoon emerged as the largest with 54 seats in parliament and although he cannot become prime minister himself, it puts him in the position of kingmaker, instrumental in determining who will take charge.

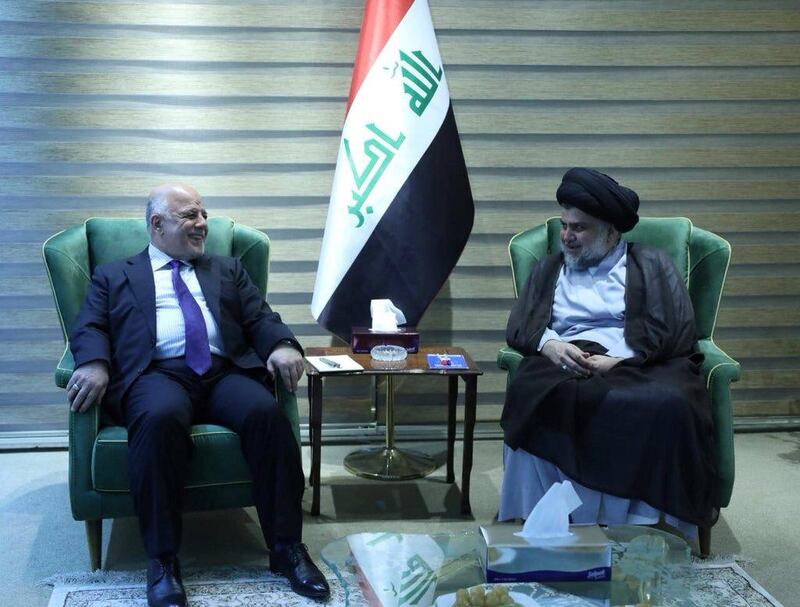

His first move in meeting current Prime Minister Haider Al Abadi on Saturday, less than 24 hours after being declared the winner of Iraq's parliamentary election, was encouraging. It is the clearest sign yet that Mr Al Sadr plans to stick to his election promise of not bowing to Tehran or Washington, despite their attempts to push their own interests. Iran, meanwhile, is labouring hard to preserve its own interests in Iraq. Qassem Suleimani, the commander of Iran's Revolutionary Guard Corps, has been on the ground in Baghdad and is seeking to forge partnerships with Hadi al Ameri's Fatah coalition and Nouri Al Maliki's State of Law. For now, they appear to be on the sidelines.

Mr Al Sadr's priorities might not be easy to reconcile with the leanings of his potential partners in parliament – and he will invariably have to make compromises that will involve downgrading some of his pledges to the electorate while promoting others. The challenge before him now is to cultivate partnerships in the greater interests of his nation and pick a prime minister who can protect Iraq's autonomy against the aggressive competition for influence, strengthen its institutions and deliver to Iraqis the things they most desperately need: schools, roads, hospitals, security and a government that is reliable, not beholden to foreign powers and free from corruption. It also behoves him to distance himself from his past as a cleric who urged attacks on US troops in the aftermath of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. His meeting with Mr Al Abadi and declaration that "our door is open to anyone as long as they want to build the nation and that it be an Iraqi decision" suggests he is making progress. Negotiations could take months, nevertheless, and the path ahead will not be easy. But the fact that Iraq, ravaged by nearly two decades of war, is looking forwards is a measure of how far it has already come.