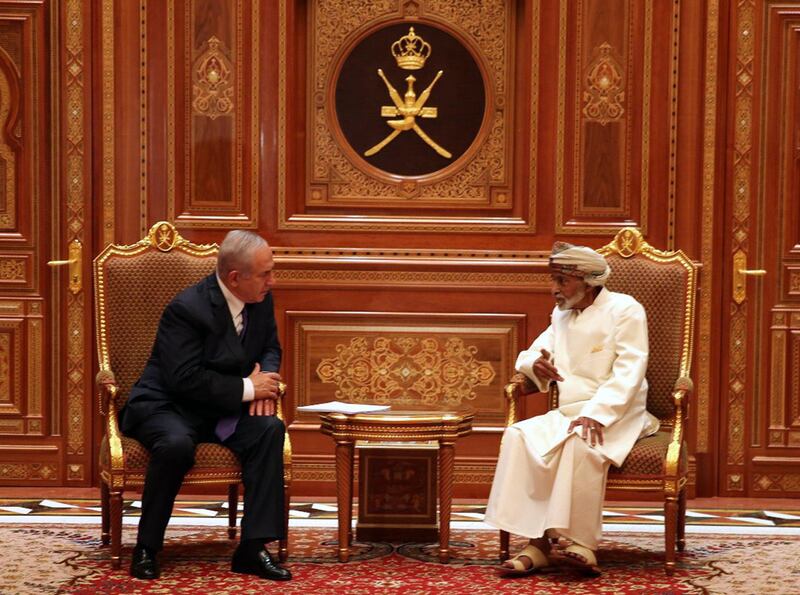

When Prime Minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu travelled to Oman last week – the first such visit of its kind in more than 20 years – commentators around the world were quick to call the meeting a “normalisation” of Arab-Israeli relations.

The two nations engineered the meeting independent of the GCC and while Oman has been a mediating influence in multiple disputes, from Yemen to the fallout with Qatar, Friday’s liaison was a political move by both parties. It by no means represents official recognition of Israel.

Yet the visit comes at a historic moment. The region is in dire need of movement towards a resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Setting aside the nature of the Israeli visit, just two days after Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas met Sultan Qaboos bin Said, the point mooted by Omani foreign minister Yusuf bin Alawi at the IISS security summit in Bahrain is an important one. “Our priority now is to put an end to the conflict and move to a new world,” he declared.

The idea of a peace deal with Israel is not a new one. Under the terms of the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative, sanctioned at

the Arab League Summit in Beirut by 57 Arab and Muslim nations, Israelis would withdraw from all Arab lands occupied since 1967, including the Golan Heights, establish normal relations with Arab and Muslim countries and declare the conflict at an end.

In 2007, then Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert went so far as to welcome the initiative and an Arab League delegation was dispatched to Jerusalem. But talks were never followed by action and any goodwill evaporated when Hamas took over Gaza later that year.

Regardless of how we have reached this point, this is a moment to be seized as an opportunity to secure a peace deal. That requires honesty from all sides but above all, it requires the rights of Palestinians to be respected and placed at the forefront of any negotiations. If the Israelis are willing to show courage and respect the Palestinians’ right to statehood, as well as their status as citizens with the same protection as Israelis, this could be the time for all parties concerned to negotiate a peace settlement that is beneficial to all.

Letting go of the past and looking forward, as Mr Bin Alawi urged, does not mean overlooking the one group of people impacted most by these talks – the Palestinians. A compromise should not mean sacrificing their rights. Indeed, with their shared interest of reining in Tehran’s adventurism, Israel stands to benefit from aligning itself with Arab states.

We are still a long way from any kind of normalised relations with Israel – but a visible willingness to compromise and acknowledgment of the importance of recognising Palestinian rights goes a long way.