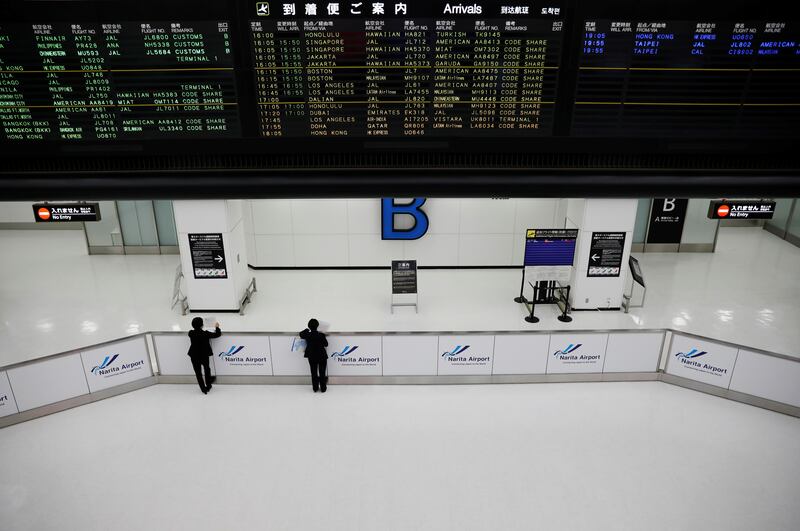

The UAE's cricket team had been looking forward to playing in the Cricket World Cup League Two for the first time since January 2020. But yesterday, the team was searching for the first flight home. Covid-19 had stopped them in their tracks, again.

The sudden change comes because of a new variant of the virus, Omicron, which is taking hold in southern Africa and the rest of world. It is already ushering in new travel restrictions. The UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the US, the UK and many others have closed their borders to travellers from several African countries.

This is a major blow for South Africa, where the strain was first spotted. It was relying on a strong tourism season after a year in which it has suffered heavily from Covid-19 and widespread unrest over the summer.

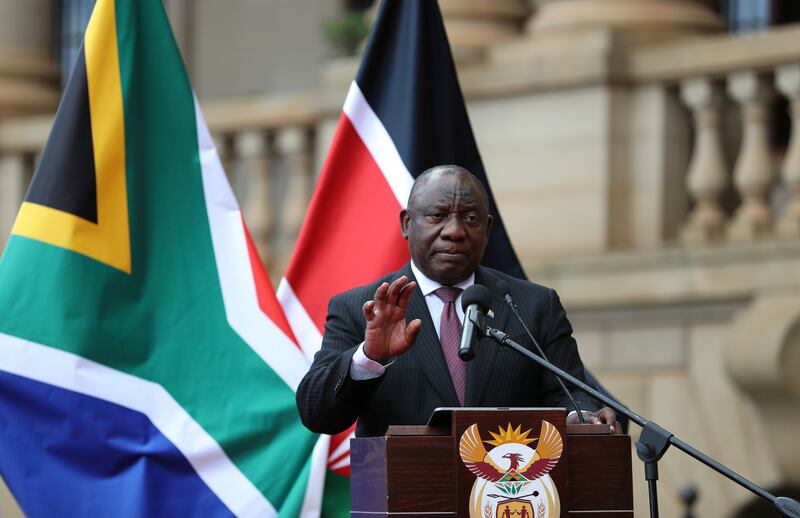

The country's President, Cyril Ramaphosa, has first-hand experience of the need to take Covid-19 seriously. The country has registered almost 90,000 deaths from it. And yet yesterday he was critical of the decision by so many countries to ban travel to his county, calling for these measures to be lifted "immediately and urgently".

However, caution from governments all over the world is understandable, particularly given the nature of this new strain. It is the most significant mutation of the virus to date, raising fears that it might be more transmissible than the dominant Delta variant today. It might even be that vaccines are less effective against it.

Nonetheless, Mr Ramaphosa also has a case. The medical and scientific community in his country have been similarly critical of what they view as an international overreaction. The chair of the South African Medical Association, Angelique Coetzee, has said only "very mild cases" have been spotted domestically. The foreign ministry is saying that the country is being unfairly "punished" for what is in actual fact the achievement of quickly spotting a new variant.

This discord between both camps reveals an important conundrum at the heart of dealing with the next phase of the pandemic. In its early days, the Covid-19 crisis was one of disaster control. Some governments failed to act quickly with devastating results. On the other hand, viruses necessarily mutate, and Mr Ramaphosa's argument is that a global, long-term policy should be agreed for the sake of global recovery.

The WHO's position reflects this. While it has said Omicron is a "very high" international risk, its regional director for Africa, Matshidiso Moeti, has called for countries to follow international health regulations to avoid flight bans. The same organisation that was calling on many countries to do more at the beginning of the pandemic, is, like South Africa, now calling for more nuance.

Both approaches have their merits. This fact underlies the complexity of managing the pandemic in the medium to long term, and the need for a global framework based on compromise between health and economic needs, particularly for the sake of poorer countries that have unequal access to vaccines.

There are no obvious right or wrongs in this latest saga, only evidence that international, not just national, action is needed to manage the pandemic. Covid-19 was fought first in hospitals and laboratories. Now, it must be fought with international diplomacy.