‘If you’re feeling depressed about the current state of this election,” said US talk-show host John Oliver, “let me give you some perspective from the Philippines.”

Speaking hours before the Philippine elections were held on Monday, Mr Oliver spent the next three minutes roasting Rodrigo Duterte, calling out the presidential candidate for routinely kissing female supporters, insulting the Pope and admitting he had no qualms about killing criminals.

“Terrifying”, “truly nauseating” and “trying to test the limits of basic human decency”, blasted Mr Oliver.

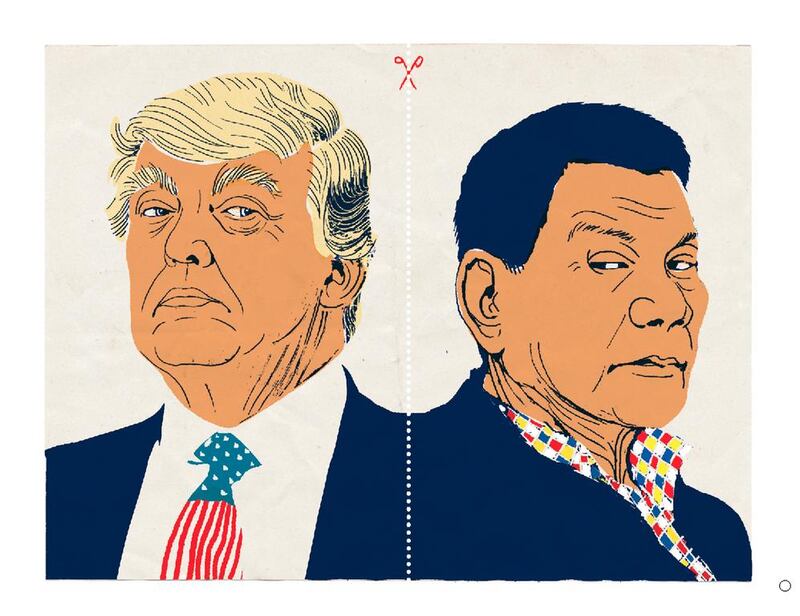

He also called Mr Duterte the “Donald Trump of the East”, a designation that has been recently made by several western media outlets, including CNN, The Guardian and The Washington Post.

The comparison is understandable, though unjustified. Because while the 71-year-old Mr Duterte, who has won the elections by a landslide, can be brash and brutal, he’s a more layered character than the hooligan being portrayed by the western press.

For one thing, Mr Trump’s bid appears to be rooted in an insatiable hunger for adulation, while Mr Duterte seems genuine in his intention to help the poor and fight corruption.

I observed this first-hand while covering their respective campaigns over the last six months. At his rallies, Mr Trump revels in provocation: pouty, vulgar and aware of his ability to inflame his supporters with prickly one-liners: Mexicans are rapists, ban Muslims, retaliate against China – the endless blitz of ludicrous pronouncements has been absolutely breathtaking. At an event last month in Superior, Wisconsin, he told the crowd: “I can be presidential, but if I was presidential I would only have about 20 per cent of you here, because it would be boring as hell.”

While Mr Duterte is far from meek, he was often unassuming on the campaign trail – a trait the media has not chosen to highlight. Motivated by the public’s clamour urging him to run for president, he reluctantly announced his bid just five months before the elections. “If only to save the republic. But I won’t die if I don’t become president,” he said.

“The media coverage has focused on the few offensive things he has said – and it’s unfair,” says Jocelyn Arriola, a political science professor born and raised in Davao, where Mr Duterte served as mayor for seven terms, totalling more than 22 years. “I’ve seen it during the last two decades – my family has seen it, everybody in Davao has seen it, and now the entire nation will get to see it: Digong [Duterte] is the kindest, most hard-working and most effective politician in this country.”

Watching Mr Duterte campaign across the Philippines, as well as talking to several of his admirers, I noticed that his election persona was distinct from his actual identity, as he consciously played to the crowd. He cracked many jokes – sometimes crude – which has encouraged the Trump comparison. While a recent quip about the rape of an Australian missionary was nothing but thoughtless and deplorable, Mr Duterte seems to have chosen humour as a tool to reach out to voters, particularly the poor majority.

His actions speak louder than words, Philippines senator Pia Cayetano told Time on Wednesday. “I’ve known him for many years and have been so impressed by the women-centred programmes they had in Davao. I’ve told him that he needs to improve his language drastically, because it distracts people from the work he’s done.”

An aura of authenticity has made Mr Duterte stand out from the polish and bombast of his four opponents, who are major personalities in national politics: the Wharton-educated interior minister Mar Roxas, incumbent vice-president Jejomar Binay, veteran lawmaker Miriam Defensor-Santiago and popular senator Grace Poe.For many of the voters I met, Mr Duterte was the best choice among all five.

In Mr Duterte’s hard-edged populism, disenchanted voters of a highly stratified society found someone willing to shake up the establishment.

“He is different from the rich and the elites who have controlled our country for so long,” said Arjay Castillo, a 24-year-old fish vendor in Manila who had only heard about Mr Duterte three months ago.

“We finally have someone who will fight for those who do not have any power,” added Mr Castillo. “I am so happy he won – because that means the common man has won.”

Indeed if there’s one clear similarity between Mr Trump and Mr Duterte, it’s that they have both tapped into the widespread public disgust with incumbent mainstream politicians who have ignored the less affluent’s growing anguish. A vote for these outsiders is a vote of protest.

While the Philippines has enjoyed six years of robust economic development under the leadership of outgoing president Benigno Aquino, poverty remains rampant, while criminality and corruption persist. The quality of social services and infrastructure have been the object of ridicule.

According to data from national research institution Social Weather Stations, a mere one per cent of Filipinos belong to the upper class, nine per cent to the middle class, while a staggering 90 per cent are considered working class. Voters are not feeling the benefits of steady economic growth – and they’re fed up. They’re willing to overlook Mr Duterte’s machismo and incendiary rhetoric because there are far more pressing problems to be addressed.

It’s unsurprising how Mr Duterte’s plan to overhaul the country’s system of government quickly attracted support, particularly when contrasted with the identical low-risk platforms of his opponents. On Tuesday, his spokesman said Mr Duterte’s presidency would seek to switch from a unitary form of government to a parliamentary and federal model, devolving power from the capital city of Manila to hundreds of neglected provinces. His spokesman also reiterated Mr Duterte’s vow to crack down on corrupt officials and tax evaders to boost government funding for public welfare.

And while Mr Trump’s deeds continue to become increasingly unsettling as he heads to his country’s general election, Mr Duterte has been giving hope to critics that his term would not be as bad as they had speculated.

After polling results revealed he had won on Tuesday, Mr Duterte declared he wished to build a powerhouse team of new faces and veteran talents – “not politicians, but managers” – to run his administration. The Philippine peso rose against the US dollar, with market strategists citing investors’ trust in the new presidency.

“I would like to reach out my hands to my opponents,” Mr Duterte said. “Let us begin the healing now.”

Let’s hope he isn’t just referring to repairing relationships with political adversaries. For the sake of the millions who put him in power, the restoration and redevelopment of his nation cannot wait.

James Gabrillo is a former arts editor at The National