.

What was most remarkable about the news this week that Buzz Aldrin had been airlifted out of Antarctica in a medical emergency wasn’t that he had fallen ill, but that he was at the South Pole. The man is, after all, 86 years old, an age when most people would have long ago abandoned golf, let alone bone-chilling jaunts to the harshest place on Earth.

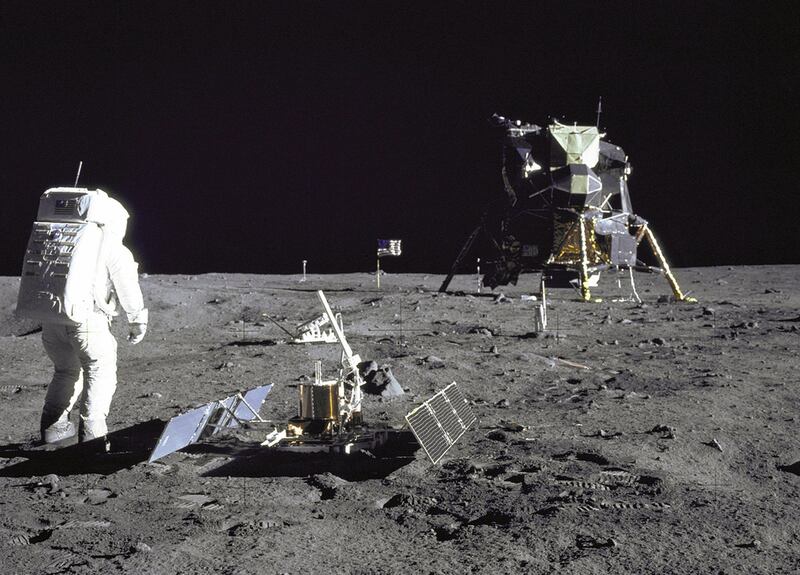

Aldrin, who followed Neil Armstrong down the ladder from the Apollo 11 lunar module on July 21, 1969 to become the second human being to walk on the Moon, is clearly a remarkable man.

But what is most astonishing about Aldrin’s sprightly longevity is that it is not unique among the 12 Apollo astronauts who, between July 1969 and December 1972, left their footprints in the dust of the Moon.

As anyone who has read The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s forensic scrutiny of the characters of the men who led America’s race into space, will know that the dozen who so boldly went where no humans had been before were not exactly physical supermen – certainly not by the standards of today’s athletes.

Like most Americans of their era – especially service personnel, as 11 of the 12 were – they drank, smoked, ate bleeding steaks and fried food with gusto, embraced life with reckless abandon and pursued what passed in Nasa’s early days for physical fitness programmes with only reluctant dedication.

So how come so many of them are, like Aldrin, still alive and kicking? What is their secret, and is it one that any of us ordinary mortals could tap into?

Born between 1923 and 1935, by statistical rights all 12 of the men who, in the words of Andrew Smith’s 2005 book Moon Dust, “fell to Earth”, should now be dead. In fact, seven are still alive, with a mean age of 83.

If that sounds unremarkable, consider this: the mean of the predicted life expectancy for American men born in the same years as the 12 Apollo astronauts is 59.5 years, which means that as a group the surviving spacemen have lived for almost two and a half decades longer than their contemporaries.

Even the five who have died did so only after having achieved a mean age of 74, outliving the mass of their Earthbound counterparts by a decade and a half. To put that in perspective, they did almost as well as a male child born in the United States in 2015 can expect to do: that one-year-old’s life expectancy, according to the Population Division of the United Nations, is little better at 76.47 years.

And that, remember, is for someone born 80 years after the youngest Apollo astronaut and 92 years after the oldest.

So how have they done it? What, exactly, is the right stuff that has allowed these 12 men to buck the odds?

None of them was exactly a spring chicken when they kicked up Moon dust – the average age of the 12 was 39. The youngest was Charles Duke, 36 when he boarded Apollo 16 (and still alive today, aged 81). The oldest was Apollo 14's Alan Shepard, who was 47 (he died in 1998, aged 74, surpassing by almost two decades his generation's anticipated lifespan of 56 years).

__________________________________

Read our health debate

Part one: Will living to 150 become the new normal?

Part two: As human lives get longer, the question is: can we afford it?

Part three: Technological advances will drive our quest to live longer

__________________________________

Perhaps it had something to do with being in the military. All except Harrison Schmidt, the last man on the Moon and Nasa's first scientist in space when he blasted off from Kennedy Space Center on board Apollo 17 in 1972, served as pilots for the US Navy or Air Force. Three – Armstrong, Aldrin and Shepard, saw combat as pilots, the first two over Korea, Shepard in the Second World War.

Maybe a mind so finely attuned to self-discipline can will itself, and its body, to keep on going when others might literally lose the will to live. So how to explain the non-military boffin Schmidt, still alive at 81 despite a life expectancy of 60 years? Easy. Statistically speaking, he could be an insignificant outlier and, of course, he is the youngest of the surviving astronauts.

But maybe the military connection as such is a red herring.

Perhaps the 12 men benefited in some way from the effects of zero gravity? Possible, but unlikely. The only documented effect of long-term exposure to zero gravity is muscle and bone wastage and, besides, there was nothing long-term about the Apollo flights, on which the astronauts spent an average of only a little over nine days. The longest was the 12 days and almost 14 hours spent in space by Apollo 17. The shortest was Apollo 13's dramatically aborted mission, which lasted just under six days. The crew of Apollo 11 spent only eight days away from Earth.

Besides, there is growing evidence that being up there is the opposite of good for your health. In 2013 scientists funded by Nasa concluded that longer trips – such as to Mars – could expose astronauts to sufficient levels of cosmic radiation to accelerate the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. How about G-forces, then? Could something about being exposed to three times the normal gravity of Earth at blast-off flip a longevity switch somewhere in the human genome?

Jet pilots – which 11 of the 12 moon-walking Apollo astronauts were – can experience even more Gs during fast, tight turns and, during a career in aviation, can do so far more frequently and for more sustained periods of time than an astronaut. But either way, the effect of exceptional G-force is to temporarily starve the brain of blood – surely that can't be a good thing in the long run?

So what’s left? Could the credit lie with nothing more exciting than efficient bureaucracy?

Perhaps the extraordinary longevity of the Apollo 12 owes less to the individual attributes of the men who walked on the Moon and more to the uncelebrated genius of the Nasa selection programme, which from thousands of potential candidates was able to identify a group of men physically and psychologically best suited to fulfilling president John Kennedy's pledge that America would win the space race.

Perhaps. Or maybe there is an altogether more inspirational explanation. Perhaps for those who have stood on the Moon, gazing back at the distant Earth as it rises above the lunar horizon, there was a life-affirming moment of revelation.

All our individual abilities, hopes and fears pale into nothing alongside the irresistible force of humankind working in harmony towards a common goal.

It would be easy for an individual to feel diminished in the vastness of space, adrift from the familiarities of life on Earth. But perhaps “the right stuff” is the ability not only to recognise that the exercise of the collective human will is our super power, but to thrive upon it – to embrace the courage of collaboration.

Gazing back at the Earth from the Moon, one can see only a thing of beauty, green and blue and unique among the uniform greyness of the universe. From 385,000 kilometres away, the human eye and mind lack the ability to differentiate, and to discriminate against, creed, race or colour. Borders, dogma, petty prejudices, self-interest and greed – all are no more. What could be more life-affirming?

In a world rapidly fragmenting along political and geographical lines and spinning towards ecological disaster, it’s a perspective that, if only we could pause in our headlong rush towards self-destruction, could yet save us all. All we need is to tap into our “right stuff”.

Jonathan Gornall is a regular contributor to The National