What a difference a day makes and Friday, March 20, was the point when the capitalist system hit the pause button in the face of the coronavirus pandemic.

Governments across the globe turned to starter versions of a universal basic income (UBI) to get their citizens and economies through the crisis. As one observer said, the tax system was built on taking a share of peoples earnings; but when they cannot earn, the system must be put in reverse to sustain livelihoods.

The idea behind UBI has undergone a revival in recent years. The prospect of artificial intelligence taking on tasks requiring human thinking led proponents to predict that UBI schemes would come to share the gains among those left jobless.

In this crisis we have moved very quickly away from the main issue being the Chinese shutdown. With the workshop of the world closed, a supply crunch loomed for exported goods. In a research note last week, Goldman Sachs said at the worst of the crisis in the Chinese heartland, up to 80 per cent of local economic activity had stopped.

Social-distancing rules and rising levels of sickness have now pitched the big economies into collapsing demand. Both sides of the economic equilibrium have cracked. The world economy is a broken seesaw. Some economists think it is not unreasonable to fear a fifth of this year’s economic output could be wiped out.

UBI is the main tool now available to policy makers to stop the slide going even further. Putting money in people’s pockets while they are under orders to stay at home allows households to continue to spend.

In the US, President Donald Trump and Congress appear poised to unleash successive waves of direct funding to Americans via cheques from the federal government to every adult. Mr Trump also spoke on Friday of invoking the 1950 Defence Production Act to direct factories to produce vital supplies that are in shortage, particularly medical equipment.

The Australian government has proposed sending out money from treasury coffers, Hong Kong put HK$10,000 in every resident’s bank account in February and Singapore made a similar offer. Denmark, Germany, Ireland and Sweden have led the way in Europe, with schemes to back up workers wages with a state guarantee. The European Central Bank has offered a €750 billion “big bazooka” to underwrite government spending.

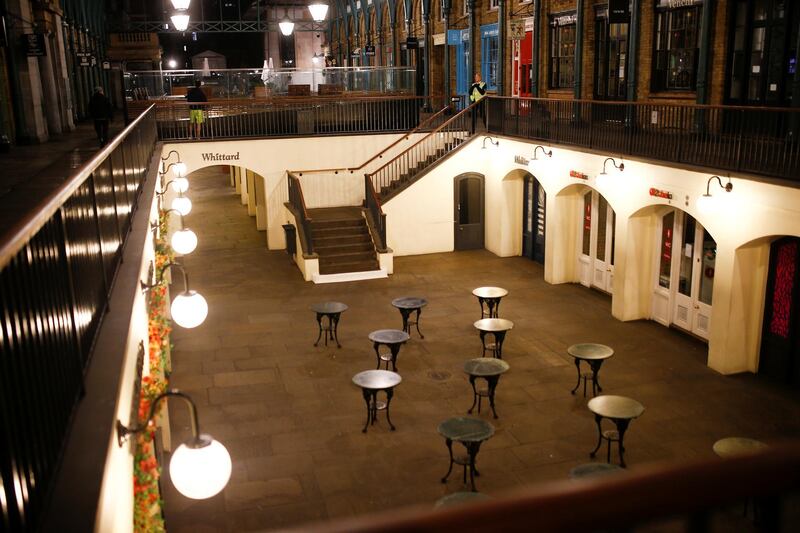

Measures announced in London on Friday put the British government firmly in line with other nations promising to maintain income levels. The UK government is to pay 80 per cent of all furloughed workers' wages.

The funding to pay for direct state provision of income for the people comes from borrowing. For those countries with their own central banks, the next step is that the Central Bank prints the currency to pick up the tab.

Conventional thinking for much of the 20th century would view this as heresy. Governments printing money were thought to be reckless actors, risking hyperinflation and instability.

Economists have turned on a dime. Ben Bernanke, the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, has warned that under “certain extreme circumstances” fiscal deficit spending is the best available alternative.

With inflation tame in all but the most inefficient countries, interest rates are near zero. Cuts seem to do little to unleash resources.

Many of the schemes outlined above are designed to be temporary. The appetite for government paying wage checks through fiscal borrowing is an immediate response to the crisis. So-called helicopter money, in which the central bank tops up private accounts directly, is for now seen as feasible only in a series of one-offs.

The opportunity presented by a more formalised UBI is that it addresses the fear of the unknown that can cripple economies.

Governments must provide flexibility and security for individuals to stay at home, stay healthy and remain engaged economic actors. The British think tank the Royal Society of Arts defines economic security as “the degree of confidence that a person has that they will have enough on which to survive, for now and the future”.

Asheem Singh, the RSA head of economics, said last week that the pandemic marks a watershed for advanced economies, bringing on change that had seemed theoretical before. “Coronavirus will be seen as an acceleration of trends that were already long-predicted by economists and futurologists like myself,” he wrote. “Whatever new world we create from this, the likelihood is that it is here to stay.”

Experiments in UBI have failed in the past. Schemes in Finland, Oakland, California and the Netherlands that gave monthly grants to limited numbers of people fell apart quickly. It did not make sense to give handouts to limited numbers of people within an unchanged national economy.

That is why the events triggered by the coronavirus mean UBI schemes are likely to transform the social contract permanently.

Damien McElroy is the London bureau chief of The National