One of the great cultural and business growth areas over the past two decades has been in education. Prestigious schools and universities from the United States and Europe have capitalised on their reputations for academic excellence by setting up campuses and study centres around the world.

The UAE has benefited greatly from this cross-fertilisation of ideas and teaching practices. So has Britain, the US and other countries.

But now British university professor Edward Vickers, chair of comparative education at Kyushu University in Japan, has complained that some English private schools setting up partnerships in China are locked into educational programmes which mean they should think again.

The schools are for the benefit of a burgeoning Chinese middle-class and must teach the Chinese national curriculum. The money raised by this partnership would help to finance other projects in the UK.

It sounds like a win-win situation but Prof Vickers points out that the Chinese national curriculum avoids or downplays contentious parts of China’s history.

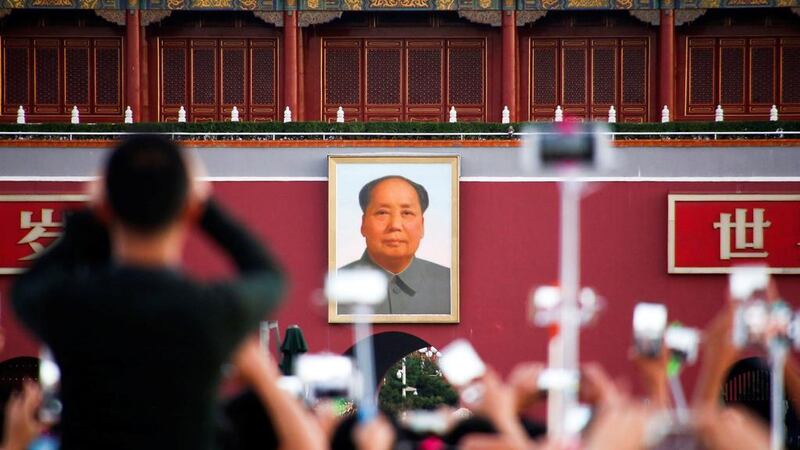

He is quoted as saying that "there will be no talk about the Cultural Revolution or the Great Leap Forward. Mao will be presented at all times as wonderful. Is this something these schools would be prepared to teach in the UK? I doubt it."

Actually, the idea that any British schools teach any significant Chinese history – what about the Boxer Rebellion or the Opium Wars? – is a bit far-fetched but Prof Vickers argues the schools should be "very uncomfortable" and "think again" about working in China.

This, it has to be said, opens a can of worms. The Chinese curriculum is in line with the thinking of the Chinese Communist Party.

That means when it comes to Chairman Mao’s dismal legacy, free and open debate will, as professor Vickers suggests, probably not happen.

That’s a pity because to understand China’s economic miracle today, students need to understand the past and the genius of Deng Xiaoping in dismantling Mao’s inhumane policies.

But the wider issue goes beyond China to all of us. How history is taught anywhere contributes to a sense of national identity through both historical facts and myths.

History teaching tends to focus on those periods when leaders from the country involved were the good guys or victims rather than the oppressors or the destroyers.

_________________________

Read more from Opinion:

[ Damien McElroy: US attempts to get Europe to toe the line on Hezbollah are meeting resistance ]

[ Raghida Dergham: Syria offers an arena for US-Russian cooperation ]

_________________________

How far do schools in Japan, where Prof Vickers is based, really teach children about Japanese aggression in the 1930s, the Nanking Massacre and other atrocities?

British children are endlessly familiar with the UK’s great role in the Second World War. But the legacy of British colonialism and, for example, how it affected our nearest neighbour Ireland, does not get so much play.

And in Ireland itself, if you want to pick a fight, mention to an Irishman that the Great Famine was indeed a despicable part of British history but it took place in the 1840s, known as the "Hungry Forties", across Europe – and Dickens' London wasn't all that benevolent either.

In the US, African-Americans have pushed to celebrate their contribution to building that nation through Black History Month but even the welcome creation of that event points out just how much the story of black Americans has been marginalised.

It took Hollywood almost a century to understand that all American cowboys were not white. The existence of black cowboys is an important historical fact only recently seen on movie screens.

And in Russia, any discussion with an educated Russian in these days of tension over Vladimir Putin's foreign policy will always include a mention that Russia defeated the Nazis in the Second World War.

True. But I have yet to have a conversation with any educated Russian who willingly points out that the Second World War began with Hitler and Stalin agreeing to destroy Poland and carve it up between them.

History, famously, is the account of the victors and different teachers rightly emphasise different stories.

But history is not just about the past. It is about how the present understands and uses the past and that is constantly changing. It is also about the prejudices we pass on to the future.

At The National's recent Future Forum, one eloquent speaker argued that we should stop using the phrase "Middle East" since it reflects a historic view of the region as seen by the British and French over the past few hundred years.

He said we should call the region more accurately “West Asia”. Changing a historical name for a region would remind us of the strong historical ties with India, Pakistan and beyond, rather than a world shaped from Paris and London.

My advice to the schools operating in China is to acknowledge the points made by Prof Vickers and then ignore them.

The benefits of education include an understanding of other cultures and other points of view.

Contact between Chinese or any other students with educators from another culture helps to promote international understanding and a civilised public discourse.

If you can learn that, then unpicking the horrors of Maoism and China’s Cultural Revolution will take place, given time. And time, after all, is what history is about.

Gavin Esler is an author, journalist and television presenter