How do the aesthetics of poetry work? It is clear that they are rooted in language, but what does this really mean? Arabic and Chinese poetry are ancient traditions. At the same time, they are entirely strange to western readers. It seems a lonely fate of poetry: to be immense and misunderstood.

When I was seven years old, poetry was a nightmare. Every evening after dinner, my father would say: “Well, it’s time to read some poems.” That spelt trouble because when Father said “read”, he meant read by heart.

Classical Chinese poetry always rhymes. So the sounds were very nice. But how could a seven-year-old know what was being talked about in those sentences? I would feel terrible when I recited those rhymes like a blind dog barks. So, however big the names of Tang Dynasty poets such as Li Bai or Du Fu, they were boring and awful to me.

This memory of my father and the recitation of lines from my childhood followed me for a long time. It was changed since I myself started to write poems. Suddenly, I realised the musical energy of those classical poems was stored in my memory and it came back to judge the sentences I wrote. The memory of those years did not allow me to write anything weak or dry or poor. I had to create my own modern Chinese poems and at the same time, qualify to follow the great tradition.

A Chinese character holds three layers inside itself: the visual, the musical and the meaning. The visual layer is not difficult to recognise. The two Chinese characters of my name “Yang Lian” are clearly different from their English spelling. Ezra Pound’s famous idea of precise images, called Imagism, was based on this.

Then, there is the deeper musical layer hidden behind the visual. Which is why it would be impossible for a westerner to know the pronunciation of the strange characters of my name. More music to a name affects not only the sounds but also the tunes.

There are four tunes in Chinese and each character has a tune. It is the basis, in fact, of the floating nature of our speech and writing, the very foundation of all classical forms of poetry.

If images are the bricks for building a poem, then the music is its architecture. And then, of course, the poetic meaning is built within this form. Long in short, we have to write three poems inside one piece at the same time. It might sound very nice but how do we do it?

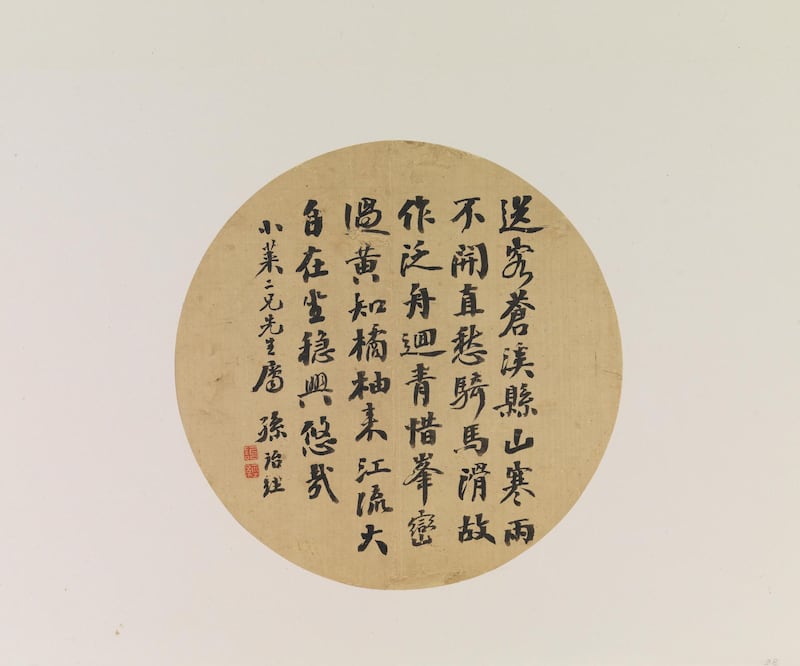

Might I use a well-known pair of sentences of the great Tang dynasty poet Du Fu’s Climb High (登高), written in 767AD, to explain the way of these works.

Please see the following:

3 無邊/落木/蕭蕭下 wú biān/luò mù/xiāo xiāo xià

without end/falling tree/rustle rustle fall

4 不盡/長江/滾滾來 bú jìn/cháng jiāng/gŭn gŭn lái

no limit/Yangtze River/roll roll come

Here, in layer one, visually, the two sentences mirror each other. Your eyes look at both lines at the same time. A poetical space is built between them that paints an autumn landscape in your sight.

In layer two, musically, if you see the sounds and the tunes that mark the sentences, they show what it is like to listen to music. The most terrified experiences are here if you pay attention to the last three sounds or tunes of the first line and if you look at the meaning of the poem – xiāo xiāo xià, means “rustle rustle fall”. The tune of “xià” comes down, exactly like the falling of the dried leaves.

It is the same in the second line: “gŭn gŭn lái” means “roll roll come”. And you can see the waves come from far away and getting wilder and bigger when they’re near and when go pass your head. This is called a ‘music painting’, or a painting in the ears. It is so when you can, so to say, listen to the pictures clearly.

There are philosophical understandings hidden inside the Chinese language too. The verbs stay always the same and never change even when the subject, the times and numbers are changed. It may seem abstract but is perhaps this aspect of the Chinese language that makes it so different from Latin languages.

The philosophical truths of the language and the immovability of verbs has confused many translators of Chinese poetry. But at the same time, don’t you think it provides also a great opportunity to write something more profound than just describing a concrete happening?

Du Fu's Climbing High was a masterpiece about a poet universally in exile. The poem went far beyond himself. It was in the traditions of Ovid, Dante, Cvitayeva, Adonis, Yang Lian – all poets in exile across space and time.

Who is not in exile now? Therefore, who has in reality not been written about in Du Fu's Climbing High1253 years ago? It is the same as my poem written in the year 1989.

It was not wrong for that poem to be translated into the past tense (1989 is past), but if you read carefully the last line “this is no doubt a perfectly ordinary year”, then my point was clear, to challenge the changeless fate and forgetful nature of human beings. Therefore, I have to agree with the translations of Brian Holton in the present tense that contextualise poems in the eternal now. The same pleasant surprise came to me from the Syrian poet Adonis. When a poetry festival in London designed a special event for both us of, I asked him, what will you read tonight, he answered: “Concerto of 9-11, 2001 – BC!” This made clear to me the very point behind Chinese and Arab poetry: the depth. It is the ballast of our boats sailing on the stormy ocean of globalisation. The reality of today is different from the Cold War era and it questions all cultures.

How can we keep our boats stable and moving in the right direction? Even more, what is the right direction? After all, we cannot help but come back to our limitations of individual thinking and expression. This is the very meeting point of all cultural transformations of the world. It is a root from where all trees grow. Poetry is our unique mother tongue as well as the future of human beings.

Yang Lian is a poet. He will speak at the Hay Festival in Abu Dhabi