This is a big week for American politics, arguably just like every other week in the years since the 2016 election of President Donald Trump. On Thursday, Mr Trump debates his Democratic challenger Joe Biden in the last such exchange before election day on November 3. It may not be a game-changer.

By last weekend, 30 million ballots had already been cast in early voting across the US. It represents nearly 20 per cent of total votes cast in 2016. Accordingly, a presidential debate may prove less than decisive in changing voters’ minds or the outcome of the election. Instead, another political contest on Thursday – one for decisive ideological control of America’s highest court – may be more significant by far.

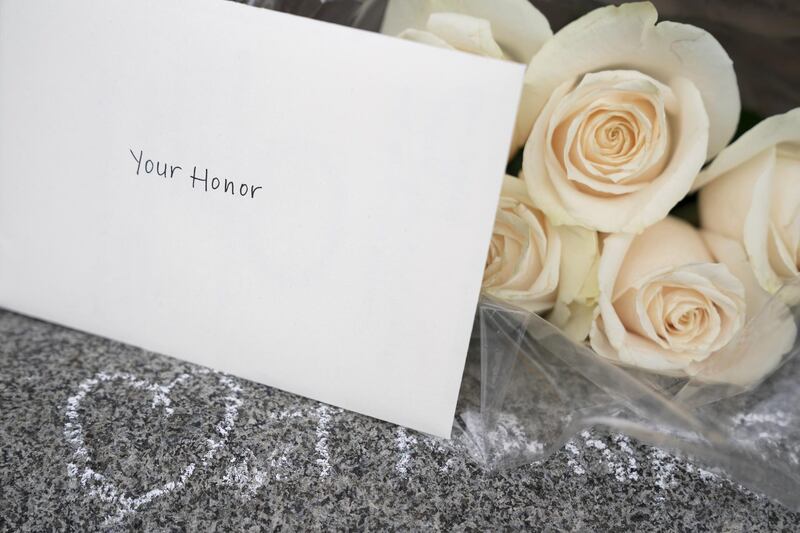

The Senate Judiciary Committee votes on Thursday on the nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to a lifetime appointment on the Supreme Court. By next week, the full Senate will have pronounced as well.

The issue is being closely watched around the world. Ms Barrett is championed by conservatives for her religious views while critics say her confirmation would shift America’s highest court firmly to the right and add to the country’s polarising cultural divide.

Ms Barrett's confirmation is all but certain – the Republican-dominated Senate is pushing for it – and she will take the Supreme Court seat held by the late liberal heroine Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The newest justice will be the youngest and only the fifth woman ever on the bench.

Interest in the somewhat arcane appointment of a Supreme Court judge is at fever pitch with Women’s March protesters taking to the streets of the US capital at the weekend to express their opposition to Ms Barrett’s nomination. One protester said it was “really scary what the future of women in this country looks like”. The marchers came up against a counterprotest in support of Ms Barrett, who was described by a conservative activist as “a role model for young women everywhere”.

Both sides are entrenched. Liberals and conservatives alike expect Ms Barrett to be a judicial activist, working to dismantle laws that govern health care, abortion rights and gun control. It’s fair to say that as a Catholic conservative woman, Ms Barrett faces demonisation on the left and lionisation on the right.

But perhaps the real issues are slightly different than framed by the noisy ongoing debate.

First, is it fair to focus so heavily on Ms Barrett’s individual beliefs? She is a practising Catholic with a demonstrably strong personal opposition to abortion. When pregnant with the last of her seven children, Ms Barrett reportedly learned of her son’s Down syndrome through prenatal testing but chose to have the baby. She has written academic articles about her views. She also has connections to a tightly knit religious community called the People of Praise, which frequently takes conservative positions on social issues as well as women’s place within the family unit.

That said, religious bigotry and stereotypes are to be deplored when considering anyone for any job, regardless of the faith or tradition the candidate belongs to. Harrying Ms Barrett for her faith is as unfair as the attempt by conservative bloggers back in 2011 to smear Sohail Mohammed, a Muslim originally from India, when he was appointed to a New Jersey state court. At the time, Mr Mohammed was routinely described as a “mouthpiece for radical Islamists", prompting then New Jersey governor Chris Christie to protest about how “unnecessary” it was “to be accusing this guy of things just because of his religious background".

As American lawyer Wajahat Ali recently pointed out, passing judgement on a person solely because of their faith can smack of religious bias. Mr Mohammed, a former electrical engineer who specialised in immigration law before his appointment as a judge, may have been victim to this even more than Ms Barrett. The kerfuffle over his elevation appears to have centred around the religion of his birth rather than any particular opinions he held.

Perhaps the larger issue thrown up by Ms Barrett’s near-certain ascent to America’s apex court is older and more complex than the culture wars between conservatives and liberals. There is an age-old perceived conflict between faith and reason, something that philosophers have long struggled to reconcile. Demonstrable knowledge is infallible and universal; belief, they argue, is not. Writing in 10th century Baghdad, Al Farabi, one of the Muslim world’s key philosophers, highlighted the need to use reasoning to justify actions and opinions in a belief system. He took his cue from Greek philosopher Plato, who championed “the beauty of reason”, which produces the capacity for justice.

Clearly, the main question that will hang over Ms Barrett in her new role is the ability to navigate between faith and reason. This is a valid issue and it would be appropriate to scrutinise her actions as a Supreme Court justice for logic and the idea of the greater common good.

Last month, American law professors Lee Epstein and Eric Posner diagnosed the country's polarisation over the Supreme Court as the outcome of an attempt by the conservative bloc to promote religious rights and push back on more than half a century of socially liberal judicial rulings.

But the issue of religious rights is contentious. Whose rights deserve primacy? The dispensing of justice should not be subservient to religious rights in a secular democracy.

Perhaps the answer lies in the words of the founders of the American experiment nearly 300 years ago. They declared that the state should favour no religion.

Rashmee Roshan Lall is a columnist for The National