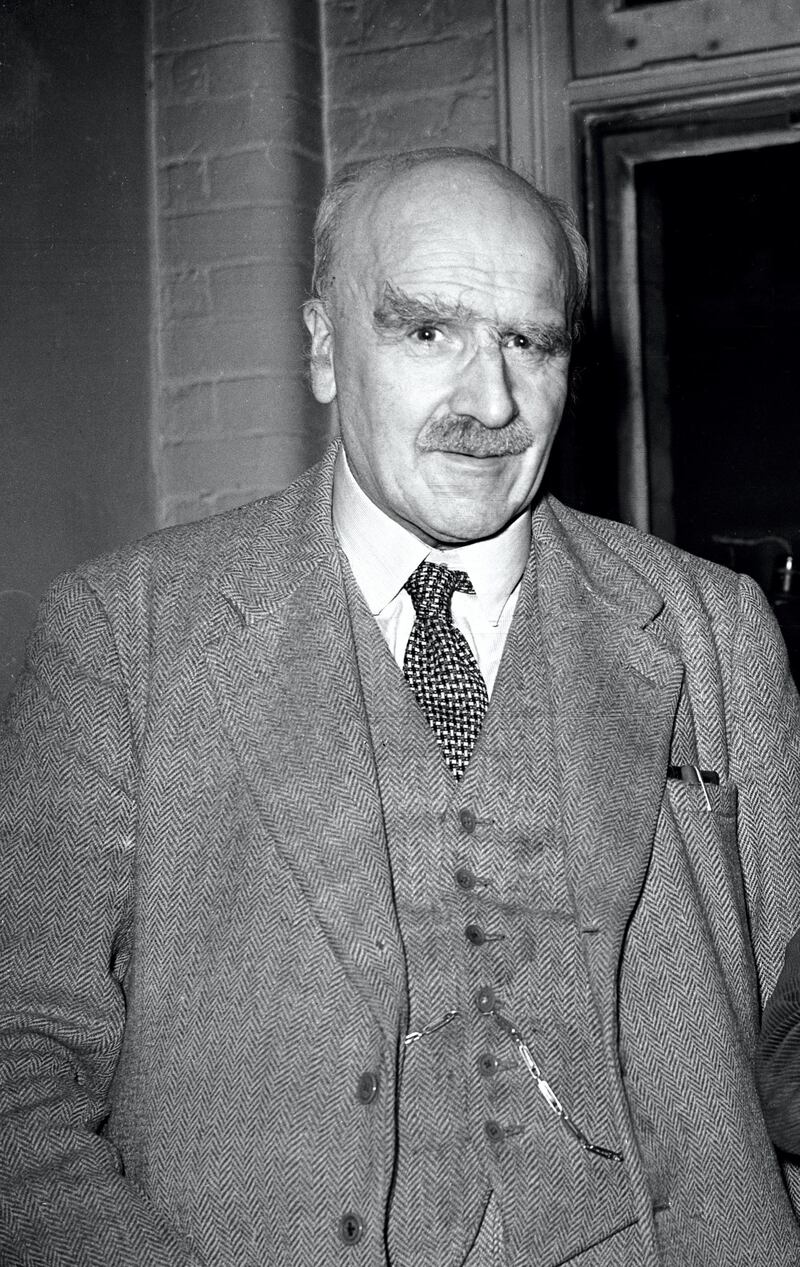

When I first heard about JBS Haldane years ago, I only knew about the final act of his life: that he was a British biologist who moved to India, became a citizen there and died there in 1964. Even that sliver of detail was intriguing. Scientists usually moved from India to the West. What prompted this man to travel in the reverse direction?

Four years ago, I started to examine his life in more detail and grew steadily more fascinated. Here was a man who, as a boy, was often a guinea pig for his scientist father; who wrote his first scientific paper when he was in the trenches during the First World War; who went repeatedly to Spain to help fight Francisco Franco’s fascist forces; who ruined his body in experiments for Britain's Royal Navy during the Second World War; who got into constant tussles with every kind of authority figure; and who wrote reams of elegant essays on science for the lay reader.

But where Haldane really spoke to me, across the years, was in his astute thinking about how science and politics intersect. Over the past few decades, we have lived in a time when scientific objectivity is often confused for apolitical neutrality. Climate change aside, scientists hardly ever took political stances, or expressed their views on matters of ideology, or occupied the sphere of the public-interest intellectual.

This was not always the case, though. In the first half of the 20th century, during Haldane’s time, scientists were vociferous about their politics and their stances on social issues – Haldane’s own voice the loudest of them all. He decried imperialism and exploitative capitalism. He criticised British and American government policies. He never made a secret of his radical politics and eventually became a card-carrying member of the British Communist Party.

His own scientific field – genetics – was perhaps the most politicised area of study in his time, and he recognised that. Even while the fundamentals of genetics were being established, the West fretted about their implications. Britain and America worried that the white race was being diluted because the “feeble-minded” and “feeble-bodied” were allowed to reproduce, or because immigrants and people of colour were having children with white men and women. The state machinery moved to prevent this. In Britain, about 65,000 people were segregated because they were considered unfit to reproduce. In America, an equal number of people were sterilised.

Haldane lambasted these measures, calling them not only unethical but also unscientific. Similarly, when Nazi Germany formulated racial purity laws and marched towards ethnic cleansing, Haldane excoriated that false science as well. The Nazi doctrine of "blut und boden" – blood and soil – was rubbish, he wrote witheringly. The only way blood differed was in its basic groups – A, B, O and AB – so "the characteristic of a race is not membership of a particular blood group". And none of the soils of Germany were unique to it, he added. "Friesland is not unlike northern Holland, Brandenburg is like western Poland."

Like other members of his class and nation, Haldane grew up believing that some races were inferior to others. But as genetics progressed and its implications became clearer, he changed his views. Race was not a meaningful category in any sense, he argued. In fact, the genes of people can vary more within a so-called race than between two racial groups, he wrote – a fact that science has repeatedly confirmed.

In his most famous essay, Daedalus, Haldane warned that as humanity refines its skills to manipulate its own genes, it will have to construct a new morality to deal with these powers responsibly. He recognised a fundamental truth: genetics is the science of differences and with such a science, the invasion of politics is inevitable.

Haldane's ideas ring with increased urgency today. All around us, we see the rise of identity politics – of an exclusionary politics based on who belongs, or does not belong, to a nation. Who should or should not cross a border. Who should or should not be thought of as a citizen.

In India, Haldane's adopted home, the government has just passed a bill to expedite the citizenship process for refugees fleeing religious persecution from three of its neighbouring countries. Refugees of every faith except Islam have been promised a quick track to citizenship. The signal is loud and clear: Muslims do not belong here.

Echoes of this are everywhere. In China, Uighurs are being segregated. In America, the president wants to build a wall to keep out Mexican and South American immigrants and refugees. In Britain, a narrative that the country should turn inward rather than ally itself with a larger union has conclusively won. There is sectarian strife in Lebanon and Iraq, and white nationalism in Europe. Around the world, communities and groups have come to believe that they are distinct, or special, or superior, even though science emphasises that this is false.

Toss genetic engineering into this mix and things only get more incendiary. Haldane was unequivocal in his belief that the social differences of class need to be stripped away. But at the moment, the danger is that if and when scientists figure out how to re-tailor the human genome, the rich will first buy themselves better genes. The inequalities of wealth will be compounded by new inequalities of ability and physiology. If we are not cautious, the gaps in human society will yawn wider and wider.

At a time like this, Haldane’s life and work offer us plenty of guidance. He urged his readers and his students to adopt the scientist’s perspective of sceptical rationality: to question authority, to demand proof for received wisdom, to make decisions based on evidence.

But Haldane was not a proponent of scientism; he did not believe that peace and progress could be delivered exclusively through science.Haldane’s university degree was in the classics, not in biology or chemistry or any other scientific discipline, and he always saw his field with the eyes of a humanist who had wandered into it.

He believed, therefore, that we have to consider our society’s frailties and foibles, even as we decide what to do with new science and technology. We have to find ways to live with each other before we discover how science can best improve the human condition. And this is an urgent task. The march of science does not wait for us to grow mature enough to know how to use it wisely. He believed, therefore, that we have to consider our society’s frailties and foibles, even as we decide what to do with new science and technology.

Haldane was, in his country and in his time, one of the most famous scientists around – perhaps even as well-known as Einstein, and certainly the most politically vocal in his profession. Since then, he has sunk somewhat into obscurity. The 21st century, though, is an appropriate time to remember him and through his work, to rediscover lessons for our own age.

Samanth Subramanian is a regular contributor for The National. His latest book is titled A Dominant Character: The Radical Science and Restless Politics of JBS Haldane